The Drowned City of Winchelsea

by Moira Allen

If it hadn't been for the gate, we would probably

have driven right by Winchelsea. It was a rainy Sunday morning

and we were headed toward Rye, primarily because we had nothing

better to do; it would be hours before we could check into our

hotel. We rounded a curve and there it was, looming dark and wet

before us: A stone gate, standing all alone across a side road,

long since severed from the walls it must once have guarded. If it hadn't been for the gate, we would probably

have driven right by Winchelsea. It was a rainy Sunday morning

and we were headed toward Rye, primarily because we had nothing

better to do; it would be hours before we could check into our

hotel. We rounded a curve and there it was, looming dark and wet

before us: A stone gate, standing all alone across a side road,

long since severed from the walls it must once have guarded.

My husband cannot easily pass such things by, so he immediately

turned onto the side road to get a better view, and then found

that he couldn't turn around, so on we went up the road and into

town. The next sight to greet our eyes was a church standing

amidst still more ruins, and that was enough to decide our

destination for the day. We parked and began to explore the East

Sussex town of Winchelsea.

We eventually discovered that the town we were exploring was not,

in fact, the original Winchelsea. That "antient town"

now lies somewhere in Rye Bay -- possibly under

the Camber Sands, though some believe it lies even farther out -- having been flooded and virtually swept away by

a series of storms in the 13th century. A high tide that

"flowed twice without ebbing" partially submerged Old

Winchelsea in 1250, and another flood in 1287 pretty much

finished the job. This flood was so severe that it inundated

nearly the whole of Romney Marsh, and diverted the flow of the

river Rother from Romney to Rye, a course it follows to this

day.

Winchelsea, however, was a popular port, often used by British

kings embarking for France, and King Edward I determined that the

city must be saved. He planned a new Winchelsea on the hill of

Iham, safe from further erosion and flooding. At the time, Iham

stood at the end of a narrow peninsula; to the north, deep waters

formed a natural harbour sheltered from weather and enemy

attacks.

Edward based the plan of the new town upon the French

"Bastide" design, a gridiron pattern that is familiar

to American visitors, as it divides the town into blocks with

wide, straight streets (instead of the endless narrow, winding

lanes common to so many British towns). Two acres at the top of

the hill, in the center of the town, were reserved for a great

church, the Church of St. Thomas of Canterbury (patron saint of

Winchelsea). Building began in 1288.

Today, this church has a rather odd, stubby look, for only a

portion of it survives. Imagine for a moment the classic cross

shape of a major church. Of St. Thomas, only the

"head" of the cross remains, consisting of the chancel

and two side chapels. The "arms" of the cross can be

seen in the ruins that flank the entrance: Stone arches and

remnants of walls, overgrown with ivy and providing a haven for

nesting birds. Of the base of the cross, nothing visible

remains, and it is not known whether this portion of the church

was even actually completed, though gravediggers are said to have

come across sections of flooring in the churchyard.

Completed or not, the church suffered a series of devastating

assaults over the centuries that left much of it in ruins. In

1337, a French raiding party attacked and seized Winchelsea,

burning some 100 buildings. On a Sunday in 1359, another French

party some 3000 strong attacked the town again, and it is

believed that someone within the town may have let them in

through the New Gate. Most of the men of fighting age in the

town were at war in France at the time, and much of the remaining

populace was either worshipping or sheltering in St. Giles

Church, which originally stood a short distance from St. Thomas.

Many of the congregation were butchered, several women were

raped, and the church was despoiled; the churchyard of St. Giles,

which was already filled with victims of the Black Death, had to

be enlarged to hold the dead. In 1360 the French attacked the

town yet again, and in 1380 the town was attacked and set afire

by a fleet of Spanish galleys (Castile being allied with France

at the time). It is believed that the nave of St. Thomas may

have been destroyed during this final attack.

The French were not the only threat facing Winchelsea,

however. Over time, the harbor that was the town's primary

reason for existence began to silt up. In the town museum

(directly across from the church), you can see a series of

mockups showing the changes in the coastline between the 13th

century and the pres dayent. When the new town was built, no

fewer than three rivers converged on the harbor; ships could sail

up the River Brede and anchor below Winchelsea's walls. Now only

the Rother remains open, and that only because it is regularly

dredged. Winchelsea no longer sits upon a near-island, but upon

a hill some distance inland from the current coastline. Where

ships once docked, sheep now graze.

The Reformation and the

Dissolution of the Monasteries brought further changes to

Winchelsea and its church, until, in the 16th century, it had

become what one writer described as "forlorn ruins."

Any stained glass windows it might have possessed were most

likely smashed by the Puritans. By the end of the 18th century,

John Wesley spoke of "that poor skeleton of Ancient

Winchelsea with its large church now in ruins," a place

almost unfit for worship. The Reformation and the

Dissolution of the Monasteries brought further changes to

Winchelsea and its church, until, in the 16th century, it had

become what one writer described as "forlorn ruins."

Any stained glass windows it might have possessed were most

likely smashed by the Puritans. By the end of the 18th century,

John Wesley spoke of "that poor skeleton of Ancient

Winchelsea with its large church now in ruins," a place

almost unfit for worship.

Restoration began in the 19th century and continues to this day;

don't be surprised to find scaffolding over some portion of the

interior when you visit. By the early 20th century, the church

still had no stained glass; the beautiful windows you will see

today are the work of Dr. Douglas Strachan (1875-1950), and were

dedicated in either 1931 or 1933. (A booklet by Strachan's

daughter offers the earlier date; a booklet on church history

gives the latter.) Strachan's daughter remembers going on a

motoring tour of the Rye area in the 1920's and visiting St.

Thomas. Noting the absence of stained glass, she told her

father, "Daddy, look at all those lovely empty windows for

you to fill!" Scarcely a week later Strachan received an

invitation to do just that. The first window he completed

memorialized the Rye Life Boat Disaster of 1928, in which the

crew of the Rye Harbour lifeboat lost their lives. This window

can be seen over the sedilia in the south wall. In the north

wall a trio of windows illustrate the themes of land, air and

fire, and sea.

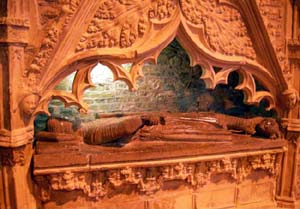

Beneath the windows in the north wall, you might suppose that you

are looking upon a series of tombs: stone effigies lie beneath

elaborately carved stone canopies, arms folded, feet resting upon

beasties that look to be a cross between dogs and lions. No

bodies are actually buried here, however; the effigies are

believed to have been brought from the Old Winchelsea Church

before it was surbmerged. They are thought to represent the

Godfrey family, but have never been precisely identified.

Conversely, the effigies along the south wall are tombs;

this is the Alard Chantry, founded by Stephen Alard in 1312. The

easternmost tomb is thought to be that of Gervase Alard; he holds

a heart, and his pillow was once supported by a pair of angels

(all you can see of the one closest to the aisle is a single

hand resting upon the pillow). The canopy over Gervase's tomb

rises from the stone heads of King Edward and his second wife,

Margaret. In the middle of each canopy, leave sprout from the

mouth of a green man.

After you've visited the church, stroll across the street to the

town museum, housed in the building that was once the Court Hall.

Hours vary; on Sunday, it is open after 2 p.m. The museum is

staffed by volunteers who are delighted to share their knowledge

of the town's history with visitors. Your tour is likely to

begin with the model of the town as it probably looked in the

late 13th or early 14th century; you can easily spot the

surviving gates that still guard the roads. The museum includes

exhibits of local industries, including lacemaking and

hop-picking. Hop-pickers were paid not in coin but in tokens,

which they could redeem at the end of the season; the museum

guide confirmed that this was quite likely so that the pickers

would remain for the entire season rather than disappearing once

they got a few coins in their pockets. One wall of the museum

lists all the town mayors since the town's beginning; the mayor

is traditionally elected on Easter Sunday and the ceremony is

still held in the old Court Hall. The museum is also where you

can sign up for a tour of Winchelsea's medieval cellars.

If you're feeling a bit peckish after your tour, consider a stop

at the New Inn across the street from the church. Built in the

17th century, it serves excellent food -- including, on Sunday, a

choice of a traditional "Sunday Roast" of beef or lamb,

provided by local farmers and butchers.

Finally, be sure to watch for one of the town gates as you leave.

According to the museum guide, history declares that the

"king built the gates and the people built the walls,"

but he suspects that while the king may have paid for the

gates, the people of Winchelsea pretty much built everything.

Strand Gate still stands near the A259; in fact, the road itself

had to be rerouted, as large vehicles kept getting stuck despite

signs warning them of the peril. The Ferry Gate is also adjacent

to the A259 (and is the one that lured us off the main road in

the first place). The Pipewell Gate stands near a hairpin turn

on the A259, and is named for a well at the foot of the hill.

The New Gate stands in open fields, an indication of how far the

town walls extended in Winchelsea's heyday. Today, silt has

turned a thriving port into a sleepy village, but it's still well

worth a stop!

The New Inn - a good place for a bite! |

An effigy from the long-drowned city of Old Winchelsea |

The Winchelsea Town Museum |

One of Winchelsea's surviving town gates |

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Moira Allen has been writing and editing professionally for more than 30 years. She is the author of seven books and several hundred articles. She has been a lifelong Anglophile, and recently achieved her dream of living in England, spending nearly a year and a half in the history town of Hastings. Allen also hosts the Victorian history site VictorianVoices.net, a topical archive of thousands of articles from British and American Victorian periodicals. Allen currently resides in Maryland.

Article and photos © 2008 Moira Allen

|