Oxford: Magic, Myth and Martyrs

by Sue Kendrick

It's not just

Matthew Arnold's "sweet spires" that dream in Oxford.

As soon as you set foot in the town you find yourself slipping

into the same kind of altered consciousness that presumably

invoked his lyrical poem, Thyrsis. It's not just

Matthew Arnold's "sweet spires" that dream in Oxford.

As soon as you set foot in the town you find yourself slipping

into the same kind of altered consciousness that presumably

invoked his lyrical poem, Thyrsis.

In spite of shoppers, students and a healthy influx of tourists,

there is a hint of surreal magic lurking in the air -- which may

account for the proliferation of fantasy writers that have found

inspiration amongst the myths, legends and bloody turbulence that

make up Oxford's kaleidoscopic past.

This colourful past begins with the legend of Frideswide, a Saxon

princess and nun who built a monastery at the "Ox" ford

crossing of the river Thames somewhere around 700 AD. The fact

that the town didn't take the name Frideswide suggests there was

a settlement of sorts already there, but you can't help feeling

that the princess missed out in the recognition stakes in more

ways than one.

Apart from establishing a very prosperous monastery on the site

now occupied by Christ Church College and Cathedral, Frideswide

also gained a reputation as a miracle worker when she very

charitably (you can't help but think) restored the sight of a

lecherous king who had been struck blind by a lightening bolt

when in hot pursuit of her maidenhood!

This seemingly miraculous cure was enough to establish the cult

of St Frideswide, with pilgrims flocking to pay homage at her

tomb and perhaps hoping to reap the benefit of her powers. The

monastery flourished along with the town that grew up around it

and quickly became a centre for educational excellence. This had

its price, however, and a town full of drunken, rowdy students

was as unwelcome then as now. Discontent between "town and

gown" finally came to a head in 1355 when a student threw a

pot of wine an innkeeper.

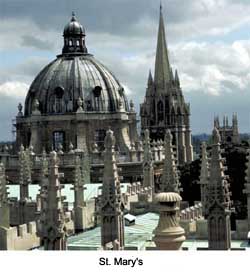

As is

usual in times of conflict, opposing parties were keen to have

their aggression sanctified by the Almighty. The antagonists

used two of the town's churches as mustering points. Citizens

rallied to the bell of St. Martin's while the university students

flocked to St. Mary's. Riots and running battles lasted for

three days, during which 63 students were killed and many more

injured. Once order had been restored, the mayor was imprisoned

and the university's power in the town increased. For the

following 500 years the mayor and corporation were forced to

parade to an annual St. Scholastica's Day service at St. Mary's

to do penance for their misdeeds. As is

usual in times of conflict, opposing parties were keen to have

their aggression sanctified by the Almighty. The antagonists

used two of the town's churches as mustering points. Citizens

rallied to the bell of St. Martin's while the university students

flocked to St. Mary's. Riots and running battles lasted for

three days, during which 63 students were killed and many more

injured. Once order had been restored, the mayor was imprisoned

and the university's power in the town increased. For the

following 500 years the mayor and corporation were forced to

parade to an annual St. Scholastica's Day service at St. Mary's

to do penance for their misdeeds.

Both St Martin's and St Mary's are still in existence, with the

tower of St. Martin's of particular interest. This dates from

the 14th century and bears a clock with ornate quarterboys in

Roman military dress. These are replicas; the originals are on

display in the Oxford museum, which not only details the growth

of the town from prehistoric times but gives some insights into

its economic growth, including Frank Cooper's marmalade factory.

St Mary The Virgin, situated in Radcliffe Square, was once the

centre for university life and housed the library and treasury.

It also hosted lectures and ceremonies and, more gruesomely, was

where Archbishop Cranmer received his death sentence in 1556.

Look carefully in the north aisle and you will see a groove in a

pillar made by the platform erected for this purpose.

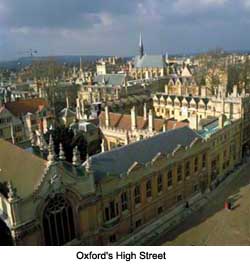

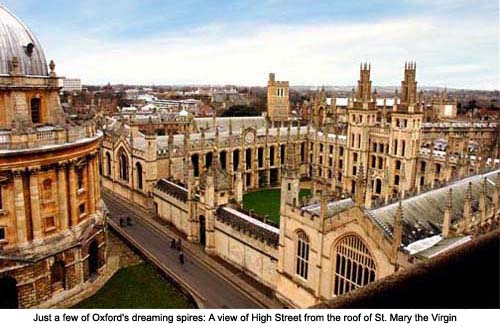

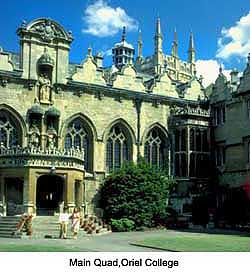

If you can manage a 127-step climb to the church roof line, the

whole panoramic view of Oxford is revealed in all its

honey-stoned, gothic-spired splendour! From this lofty vantage

point, glimpses of most of the town's 39 colleges can be seen:

solid buildings of age-worn stone embracing neat quadrangles of

carefully tended lawns. Each has a tale to tell, most of which

can be heard by taking one of the regular, organised tours that

take place around the colleges throughout the year. If time is

short, though, make sure your trip includes the magnificent

Christ Church College and Cathedral, possibly the jewel in the

Oxford crown and certainly the centre of Oxford's ecclesiastical

beginnings.

These glittering gems occupy the same site within the town

centre. Open every day of the year apart from Christmas day,

the Cathedral contains the shrine of St. Frideswide herself,

rebuilt and restored after Henry VIII's efforts to smash and

destroy it during the dissolution of the monasteries in 1538.

Another rarity in the Cathedral is the Becket window, which shows

the murder of Archbishop Thomas Becket. Henry VIII ordered all

depictions of this murder to be destroyed, but the Becket window

was preserved simply by blocking out the face.

The present building dates from the late 12th century, replacing

the previous priory church, which was deliberately destroyed by

fire. Little is made of the St Brice's day massacre, perhaps

with good reason, as this is an appalling case of ethnic

cleansing that few townships would be proud of.

In 1002, King Aethelred (the Unready) had a hard time stemming

the waves of Viking invaders that were looting and pillaging the

country and demanding higher and higher rates of Danegeld. In

desperation, he issued an edict allowing the lawful killing of

any Dane found in the country. This had little effect against

the heavily armed raiders, but devastating consequences amongst

the settlers, traders and crafts people living in towns such as

Oxford.

On 13 November, St. Brice's Day, the Oxford Danish community took

refuge in St. Frideswide, hoping that the sanctuary of the church

would protect them from the incensed townsfolk. It was a forlorn

hope. The building was razed to the ground with the loss of many

lives. The King of Denmark's sister, Gunnhild, and her family

were said to have been amongst those that perished.

Christ Church College, which lies within the cathedral

grounds, was originally planned as Cardinal College by Thomas

Wolsey. The son of a humble butcher, Wolsey rose to become the

most powerful man in England, until he got in the way of Henry

VIII's plans to divorce the first of his six wives, Catherine of

Aragon. In typical fashion, Henry stripped Wolsey of his power

and refounded the college in 1546 as Christ Church College and

promoted the priory church of St. Frideswide to a cathedral,

making it the smallest cathedral in England. Christ Church College, which lies within the cathedral

grounds, was originally planned as Cardinal College by Thomas

Wolsey. The son of a humble butcher, Wolsey rose to become the

most powerful man in England, until he got in the way of Henry

VIII's plans to divorce the first of his six wives, Catherine of

Aragon. In typical fashion, Henry stripped Wolsey of his power

and refounded the college in 1546 as Christ Church College and

promoted the priory church of St. Frideswide to a cathedral,

making it the smallest cathedral in England.

A preoccupation with size is something that features quite

strongly in the design of Christ Church College. The Great

Quadrangle, or Tom Quad as it is affectionately known, takes its

name from the gatehouse tower built by Christopher Wren. A huge

bell by the name of Great Tom hung here and tolled once for each

scholar (101 times!) at 9.05 pm each day.

The quad itself is a wide and spacious area flanked by the

elegant symmetry of the university buildings. The combination

of spacious confinement certainly makes you feel insignificant

when strolling around the open-roofed cloisters. Not that this

cut much ice with Cromwell! During the Civil war, after he ousted

Charles I, he used the area to graze cattle and then went on to

slight the city in 1650 by removing its fortifications. He also

assumed the chancellorship of the University and replaced many of

the officials with his own favourites.

By contrast, the Peckwater Quad is small and enclosed, with the

buildings crowding and jostling around you. This was once the

site of a medieval Inn but now houses the Library as well as

student accommodation.

Charles Dodgson (better known as Lewis Carroll) was once one of

these students and these quads may well have been the inspiration

behind the "drink me" bottles encountered by Alice on

her trip to Wonderland in which she alternatively grew very tall

and then very small.

The fictional Alice actually had a real-life counterpart. She

was the middle daughter of Dean Liddell, who was in charge of the

cathedral. Dodgson befriended all the Liddel girls, but Alice

quickly became his favourite. His Wonderland and Looking Gass

stories were written for her, and he often used to take her to a

nearby shop in St Aldate's, which still exists and is to be found

opposite Christ Church College. Here Alice would buy barley

sugar, and the shop itself is featured in Through the Looking

Glass, where the fictional Alice is served by a bad tempered

sheep.

Unfortunately the shop these days is rather a disappointment.

You can still buy barley sugar and other sweeties, but the array

of tourist junk spoils the illusion somewhat.

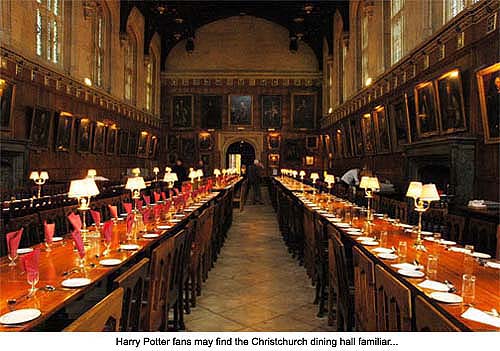

Fortunately illusion holds up well when you enter Christ Church

College Great Hall. This is everything you expect a medieval

banqueting hall to be: oak-panelled; huge fireplaces; rows of

blackened, scarred but highly polished dining tables set to feed

over 300 students each day. The hall also features a raised High

Table and walls festooned with paintings, including the college's

founder, Henry VIII, and some of the 13 prime ministers educated

at Christ Church.

Be warned! On entering the hall you may well experience a sense

of déjà vu. Fans of the Harry Potter films will

instantly recognise the Great Hall of Christ Church as the

setting for the dining scenes at Hogwarts School for Wizardry.

Other scenes were also shot at the college, which very neatly

continues the fantasy tradition begun by Dodgson towards the end

of the 19th century.

Fact, though, is often stranger than fiction and the Christ

Church College Dining Hall has seen its fair share of oddities.

During the English Civil War, Charles I held his parliament in

this vaulted building with the full support of the staunchly

royalist University. Elizabeth I enjoyed a play from the vantage

point of the raised table and Charlie Chaplain sampled a good

dinner from one of the many tables used to feed the students,

none of which have ever left the hall since their placement! (The

tables that is, not the students!)

No

university town would be complete without a good library and the

one in Oxford is very special indeed. The Bodleian Library

houses literally millions of books due to the fact that its

founder, Sir Thomas Bodley, made an arrangement with the

Stationers' Company that a copy of every book published should be

given to the library. Unfortunately it's no good applying for a

borrower's ticket as none of the books can be removed from the

premises! In fact, in 1645 the library refused even King Charles

I the loan of a book! No

university town would be complete without a good library and the

one in Oxford is very special indeed. The Bodleian Library

houses literally millions of books due to the fact that its

founder, Sir Thomas Bodley, made an arrangement with the

Stationers' Company that a copy of every book published should be

given to the library. Unfortunately it's no good applying for a

borrower's ticket as none of the books can be removed from the

premises! In fact, in 1645 the library refused even King Charles

I the loan of a book!

The good news is that the Radcliffe Camera is now a private

reading room for the Bodleian library, adding to a total of

nearly 2,500 seats available for serious-minded scholars. This

very distinctive building was built in 1749 by James Gibbs' and

was originally intended as a library devoted to the sciences.

(The word "camera," by the way, does not refer to

photography, but means "chamber.")

Neither books or science proved much help to Archbishop Thomas

Cranmer and his fellow Bishops, Ridley and Latimer, when they

came to the notice of the Catholic Queen, Mary I. Concerned that

their Protestant influence could jeopardise the fragile

restoration of the Catholic faith, she had no qualms in throwing

them into Oxford's Bocardo prison, where they were cross-examined

at the Divinity school and tried for heresy.

Ridley and Latimer were burned at the stake in what was once the

town ditch but is now Broad Street. Worse was in store for the

unfortunate Cranmer. He was made to watch the grisly proceedings

from St Michael's tower, which proved enough to make him renounce

his faith. Not that it did him any good. Mary wasn't known as

"Bloody Mary" for nothing. On 21 March, 1556 he

followed his brother bishops to the stake and met a similar fiery

end. A cross in Broad Street marks the site of the burnings and

there is a memorial to the martyrs in St. Giles.

If Cranmer's experience of royal wrath reduced him to ashes, that

of the Empress Matilda very nearly ended in frostbite! Finding

herself besieged in Oxford's castle by King Stephen, she achieved

an ingenious escape by wrapping herself in a sheet and slipping

over the castle walls during a violent snow storm. This was just

one of many spats in the civil war between Matilda and Stephen

over who would wear the crown following the death of Matilda's

father, Henry I, in 1135. The Empress, not being very well

liked, soon found herself opposed by Stephen, Henry's nephew, who

claimed his uncle had appointed him heir on his deathbed. This

was just one of several of Matilda's close escapes during the

ensuing conflict.

Little now remains of the castle built in 1071 by Robert d'Oilly,

except its motte and a small stone keep. It's worth a look,

though, especially in wintry weather, as who knows what shrouded

figure you may see flitting through the gloaming!

If

spectral figures and bleak winds are not to your taste, then the

Ashmolean Museum has plenty to interest. Its present collection

of art and antiquities is based on an early 17th century

collection by John Tradescant, who was a royal gardener. He

gathered most of the rarities in the collection when visiting

Europe to search for plants. The collection was inherited by

Elias Ashmole, who donated it to the University of Oxford in

1683. If

spectral figures and bleak winds are not to your taste, then the

Ashmolean Museum has plenty to interest. Its present collection

of art and antiquities is based on an early 17th century

collection by John Tradescant, who was a royal gardener. He

gathered most of the rarities in the collection when visiting

Europe to search for plants. The collection was inherited by

Elias Ashmole, who donated it to the University of Oxford in

1683.

One of its most prized possessions is the Alfred Jewel. This is

an incredibly beautiful artefact whose purpose is not entirely

clear. It bears the inscription "AELFRED MEC HEHT

GEWYRCAN," meaning "Alfred ordered me to be made."

It has been dated to the reign of Alfred, 871-899 and was

discovered four miles from Athelney, where Alfred had founded a

monastery. Made of gold, enamel and rock crystal, the purpose of

the jewel is not known. It could have been an "aestel,"

an object that Alfred sent to each bishopric when his translation

of Gregory's "Pastoral Care" was distributed. Each

aestel was worth 50 mancuses (gold coins), so was a very valuable

object. Aestels may have been used as book pointers. If so, there

should have been several such jewels, but so far no others are

known to exist. Others say that the jewel was a symbol of office,

either of Alfred or of one of his officials. The figure on the

Jewel is enigmatic; one theory has it as a representation of

Christ, while another is that the figure is the personification

of Sight.

Alfred was known as the greatest of Anglo-Saxon kings and through

his many endeavours against the Vikings was the only English king

ever to be given the title "Great." One of his biggest

achievements was establishing a defensive strategy consisting of

a network of fortified towns. The aim was to guard critical

strategic points against the Danes and provide a place of refuge

for the people of the surrounding countryside. Oxford was one of

these places, which were known as burhs by the

Anglo-Saxons.

Much is known about Alfred's military exploits and a little

regarding his lack of culinary expertise (remember those burnt

cakes?). Few realise, though, that legend has attributed to him

the founding of Oxford University, something historians say is

not as unlikely as it seems. Alfred was a great lawgiver and

passionately interested in education. He founded a school at

Winchester and taught himself Latin at the age of 40.

Mysterious jewels, nuns with miraculous powers,

queenly spectres -- no wonder Oxford has proved a fountain of

inspiration to the many writers and poets who have lived, worked

and studied here. In fact, the town hosted possibly the most

famous writers' group in the country: the Inklings. Its members

included C S Lewis, author of the Narnia books; J R R Tolkien of

Hobbit and Lord of the Rings fame; Charles William,

author of War in Heaven; Owen Barfield, author of The

Silver Trumpet; and many others of lesser fame. Mysterious jewels, nuns with miraculous powers,

queenly spectres -- no wonder Oxford has proved a fountain of

inspiration to the many writers and poets who have lived, worked

and studied here. In fact, the town hosted possibly the most

famous writers' group in the country: the Inklings. Its members

included C S Lewis, author of the Narnia books; J R R Tolkien of

Hobbit and Lord of the Rings fame; Charles William,

author of War in Heaven; Owen Barfield, author of The

Silver Trumpet; and many others of lesser fame.

The group usually met in Lewis' or Tolkien's rooms but meetings

were held in several of the town's pubs, most notably the Eagle

and Child (or more affectionately, the Bird and Babe). This is a

comfortable old pub on the Woodstock Road, serving good food with

a homey atmosphere. There is a display of Inklings memorabilia

in one of the rooms including photographs of members. Being very

partial to their beer and smokes, the Inklings also met in

several other pubs in the town, including the Lamb and Flag on

the other side of St. Giles; the White Horse on Broad Street

between Blackwell's and the Bodleian library; and the King's Arms

at the junction of Broad Street/Holywell Street and Parks Road --

which incidentally, serves excellent food. It's a good place to

end a day of dreaming amid the spires!

Related Articles:

- Oxford Timeline, by Darcy Lewis

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/towns/oxtime.shtml

- The Ashmolean Museum: Oxford's Window on the Ancient World, by Sean McLachlan

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/museums/ashmolean.shtml

- Oxford's Museum of the History of Science, by Sean McLachlan

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/museums/science.shtml

- The Hidden Churches of Oxfordshire, by Louise Simmons

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/churches/oxfordshire.shtml

- A Taste of Oxford: Sauce, Sausage and Hollyhog Pudding, by Dawn Copeman

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/taste/taste05.shtml

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Sue Kendrick is a freelance writer living in the English Midlands. She has written many special interest articles for magazines and newspapers and contributed an uncountable amount of news stories to her regional newspaper. She edits and publishes WriteLink (http://www.writelink.co.uk), a UK writers' resource website and monthly newsletter. She also writes fiction and has won several prizes for her short stories. When not writing, she likes to walk, ride, read and pursue her interest in small scale farming (not necessarily in that order!). For more information, visit http://www.suekendrick.co.uk.

Article and photos © 2006 Sue Kendrick

High Street from St. Mary's, Quadrangle, and Radcliffe Camera photos by Sue Kendrick; additional photos courtesy of Britainonview.com

|