Northwich: The Town With That Sinking Feeling

by Sue Wilkes

Northwich's fortunes were built on salt. The 'wyche' towns of Cheshire -- Northwich, Middlewich, and Nantwich -- were all known for their salt industries in Victorian times. Archaeological evidence suggests the Romans also took advantage of the local brine springs to extract this vital foodstuff. The town's industrial past left a unique legacy: its unusual half-timbered buildings which could be 'jacked up' and moved to escape the devastating consequences of the salt workings. Northwich's fortunes were built on salt. The 'wyche' towns of Cheshire -- Northwich, Middlewich, and Nantwich -- were all known for their salt industries in Victorian times. Archaeological evidence suggests the Romans also took advantage of the local brine springs to extract this vital foodstuff. The town's industrial past left a unique legacy: its unusual half-timbered buildings which could be 'jacked up' and moved to escape the devastating consequences of the salt workings.

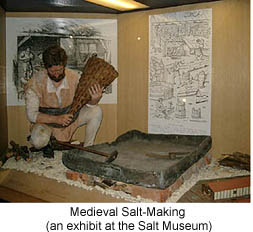

The earliest written evidence for salt-making in Northwich is in Domesday Book (1086), created for William the Conqueror after the Norman Conquest in 1066; a salt house is mentioned, belonging to Earl Hugh Lupus (the 'Wolf.') Evidence of salt production in Cheshire may date back to prehistoric times; crude pottery vessels have been found for making salt 'cakes,' and lead salt pans from Roman times have been discovered. The traditional method for extracting fine white salt from brine was to boil it up in immense pans until the water evaporated. This meant the town suffered with great clouds of smoke and steam, as antiquarian John Leland noted in the 16th century: "Northwich is a pratie market town but fowle, and by the Salters houses be great stakes of smaul cloven wood, to seethe the salt water that thei make white salt of." (Cheshire, Fred H. Crossley, 1949.) Pollution was a problem in the town until the 1950s, when effective bye-laws were introduced.

Salt boiling or 'walling' and all the processes were strictly controlled by the authorities from medieval times, with special officers appointed by the court. The Pan Cutters controlled the size of the salt pans and measured them; the Gutter-viewers inspected the channels of brine which interlaced the streets; the Killers of salt supervised buying and selling the salt.

By the reign of Charles I, over 200 'wyches' or salt houses were busily producing salt, but the tumult of the Civil War meant an end to peace. Parliamentarian Sir William Brereton had a stronghold here; in 1642 Sir Thomas Aston attacked the town in the King's name, but was forced to retreat. Later that year the Royalists ousted Brereton, and garrisoned the town for the King. By the reign of Charles I, over 200 'wyches' or salt houses were busily producing salt, but the tumult of the Civil War meant an end to peace. Parliamentarian Sir William Brereton had a stronghold here; in 1642 Sir Thomas Aston attacked the town in the King's name, but was forced to retreat. Later that year the Royalists ousted Brereton, and garrisoned the town for the King.

The discovery of rock salt (which can be mined) in 1670 near the town meant a sudden growth in the town's prosperity, but transport links were still poor. Salt was carried from the town to other parts of the country by pack pony. At one time, salt was highly taxed, and a fair amount of smuggling went on. One good story has it that in the district of Rudheath, the authorities became worried by the surprisingly large number of funerals in the area; an investigation took place, and one of the coffins was found to be full of salt! (Cheshire -- Traditions and History, T.A. Coward, 1932.) The salt tax was not abolished until 1825; once removed, the industry greatly increased its output.

Working in the salt industry was felt by the workers and their bosses to be comparatively clean, healthy work compared with other industries, such as working in the coal mines. The use of very small children in the rock salt mines does not appear to have been common practice, as in the collieries. In the salt works, however, as late as the 1850s, it was customary for young lads of age 9 or 10 to help their fathers. Often a man would rent a salt pan, and the whole family would assist with tending it, even if there were babes-in-arms to be looked after. What most shocked the Victorian reformers, however, was that the women workers in the salt works took off their dresses and worked in their petticoats due to the intense heat - working next to men dressed only in trousers. It was heavy work, too, raking the salt with huge iron rakes from the base of the salt pans; the lumps of salt, when dried, had to be loaded and moved, then broken up by hand. Scalds and burns from the hot salt pans were common. 12-hour shifts were usual, but increased legislation (the Factory Acts) meant that children and women were no longer allowed to work at night, and compulsory education was introduced for children.

As more and more mining took place, the ground underneath the Northwich area was over-run with tunnels, often flooded with water. Subsidence had always been a problem in the area, (there were literally hundreds of salt borings and mines in the town) but around the 1870s, the practice began of pumping out the brine from the flooded mines, and using it to supply the salt works. This had catastrophic effects. As more and more mining took place, the ground underneath the Northwich area was over-run with tunnels, often flooded with water. Subsidence had always been a problem in the area, (there were literally hundreds of salt borings and mines in the town) but around the 1870s, the practice began of pumping out the brine from the flooded mines, and using it to supply the salt works. This had catastrophic effects.

Houses, shops and offices disappeared without warning; the Great Subsidence of 1880 caused a great upheaval. In 1891, a Brine Subsidence Compensation Act was introduced to compensate businesses for subsidence; a special mode of construction was recommended for buildings so they could cope with the effects of mining. The light timber-framing of the Middle Ages was re-introduced, and instead of building on conventional foundations, the buildings had 'jacking points' incorporated into the timber frames. This meant that if the ground sank beneath it, a building could be jacked up to a level position, or even moved on rollers to more stable ground. For example, the Bridge Inn, which weighed 55 tons, was moved 185 ft in 1913. Even the main town bridges (Hayhurst Bridge, 1898; Town Bridge, 1899) were designed by Colonel John Saner to be partially floating structures to counteract any ground movement. The Hayhurst Bridge, which weighs 429 tonnes, is supported by four floating pontoons, it was the first electrically operated road swing bridge in the world.

Even so, subsidence continued to be a problem in Northwich. The collapse of Marston Hall Mine in 1907 led to part of a canal disappearing; in 1928 the Adelaide mine, the last rock salt mine in Northwich, collapsed, and rock salt mining moved to Meadowbank in Winsford, where mining still takes place today -- over 2.5 million tons is extracted every year.

A journey through history

The best place for visitors to begin exploring Northwich's love-hate relationship with salt is the Salt Museum on London Road. There are displays on the way salt helped to preserve food, the social history of the salt industry, a gallery about the River Weaver with model boats, and there are interactive exhibits for the kids to play on. The Museum is housed in the old Northwich Workhouse, built in 1837.

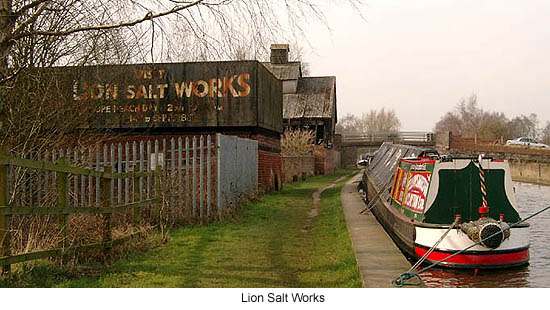

To discover how salt was traditionally produced from brine, a trip to the Lion Salt Works is a must. Recently featured on BBC TV's Restoration programme, the Works has an exhibition centre, 'nodding donkey' brine pump and horizontal steam engine. The Lion Salt Works Trust hopes to restore the site and create a working industrial museum. The only surviving open pan salt works, it was owned by the Thompson family, and produced salt from natural brine (as opposed to sea-water) until 1986. Close by, the 'flashes' (lakes), a wild bird habitat, indicate the sunken ground where mine workings collapsed.

As the Lion Salt Works is only open in the afternoons, it's a good idea to visit the Salt Museum in the morning (it has a coffee shop) and drive to the Lion Salt Works in the afternoon (phone to confirm opening hours.)

Alternatively, take a stroll through Northwich town centre -- a Town Trail leaflet is available -- and wonder at the black-and-white timbered 'movable' buildings, such as the Public Library. Built in 1909, as a gift to the town by Sir John Brunner on the site of an older library, this building once contained the first Salt Museum in the town. Look out for the carved mythical creatures on the front of the ROAB Silver Jubilee Club (Witton Street.) The Old Post Office (now the Penny Black pub) is the town's largest liftable building, built in 1814-19; but there are many others to see.

The Anderton Boat Lift, just a short drive from Northwich town centre, is literally one of the biggest attractions of the area. Why was this immense structure built?

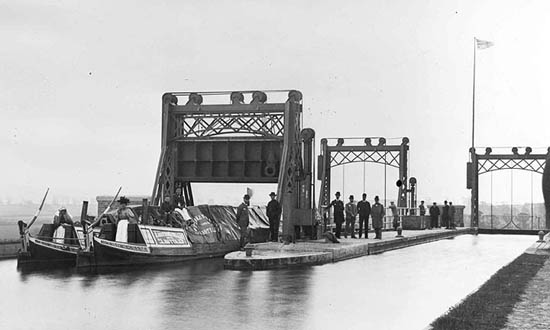

Early in the 18th C., businessmen and merchants wanted to speed up the export of rock salt, and the import of coal into the region to fire up the salt pans, (a ton of coal was needed to produce 2 tons of salt); the proposal for the Weaver Navigation was born. In 1721 an Act of Parliament enabled the River Weaver to be made navigable from Winsford up to Frodsham Bridge. During the Industrial Revolution, trade increased and businessmen hit a problem. Often, cargoes needed to be transferred between the River Weaver and the Trent and Mersey Canal, a busy trade route for the salt mines and Potteries -- but the two waterways had a 50ft height difference.

The solution was a hydraulic lift -- the Anderton Boat Lift, designed by Edward Leader Williams and Edwin Clark. This 'Cathedral of the Canals' is a monument to Victorian engineering and the world's oldest boat lift; it inspired similar lifts in Europe and Canada.

Built in 1875, the Lift was an innovative link, raising and lowering boats from one waterway to the other in vast 'caissons' (troughs) of water; in practical terms, lifting each boat on a portion of canal. A steam engine and pump operated the hydraulic rams. Going through the Lift was surprisingly speedy; it took less than ten minutes to lift a 72ft narrowboat weighing 60 tons up to the canal. The caisson itself weighed 250 tons when full of water.

As the years passed, however, corrosion of the Lift's hydraulic rams was a continuing problem, due to high levels of chemicals in the Weaver from nearby industries. In 1908 the Lift was converted to electrical operation by engineer John Saner (the same Colonel Saner who designed the town bridges.) The Lift was declared a Scheduled Ancient Monument in 1979, and operated until the winter of 1983, when serious corrosion was discovered in the structure. The pride of the waterways then lay rusting for twenty years as British Waterways, which cares for the Lift, was unable to fund repairs. The Lift fell silent until restoration began in spring 2000.

The Anderton Boat Lift re-opened to the public in 2003 after a £7 million restoration made possible by years of hard work and fund-raising by the Waterways Trust, Anderton Boat Lift Appeal, Heritage Lottery Fund, and many others. More than a mile's worth of welding was required to cover more than 1000 repairs to the structure; over 3000 separate components had to be dismantled, cleaned, repaired and re-assembled. The 1875 hydraulic mode of operation has been recreated; the 1908 electrically operated section of the Lift has been retained as a static monument.

Families can journey through the Lift on British Waterways trip boat Edwin Clark. Disabled visitors are catered for with a hydraulic wheelchair lift onto the boat; there is also a disabled toilet. At the Operations Centre, see the Lift Operator in the Control Room and find out how the Boat Lift works. Children can have fun on the interactive exhibits; there is also a nature trail to explore, and a pleasant walk along the River Weaver.

Related Articles:

- Nantwich: The Town That's Worth Its Salt, by Sue Wilkes

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/towns/nantwich.shtml

- Chester, by Sue Wilkes

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/towns/chester.shtml

Getting There:

- Salt Museum

- 162 London Rd, Northwich, CW9 8AB.

- Tel: + 44 (0)1606 41331

- How to get there: the Museum is half a mile south of the town centre on the A533. It is well signposted from the A556.

- Lion Salt Works

- Lion Salt Works, Ollershaw Lane, Marston, Cheshire, CW9 6ES.

- Tel: + 44 (0) 1606 41823

- Directions for Salt Works from Salt Museum: Turn left out of Museum car park, follow London Rd until traffic lights, turn right onto Chesterway. At next traffic lights, turn right, follow Chesterway till you reach large roundabout. Take 2nd exit of roundabout (New Warrington Rd), follow signs for Lion Salt Works at Marston -- Works is on right, opposite Salt Barge inn.

- Anderton Boat Lift

- Lift Lane, Anderton, Northwich, Cheshire, CW9 6FW (3 miles from Northwich town centre -- also well signposted.)

- Visitor centre and Operations Centre is open 10am - 5pm, 7 days a week.

- Tel: + 44 (0) 1606 786777.

- Tourist information office:

- The Arcade, Northwich, CW9 5AS

- Tel: + 44 (0) 1606 353534

- Boat trips are available from Town Bridge in the summer (phone TIC for details.)

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

|

Sue Wilkes is a member of the Society of Authors. Her book Narrow Windows, Narrow Lives: The Industrial Revolution in Lancashire, an evocative look at everyday life during the Industrial Revolution in Lancashire, was published by Tempus (History Press) in 2008. Sue's next project is Regency Cheshire for Robert Hale. She lives in Cheshire with her family and two gerbils. To find out more visit http://suewilkes.blogspot.com/.

|

Article & photos © 2005 Sue Wilkes

Archive photo of Anderton Boatlift © British Waterways

|