Lynton and Lynmouth: The Twins of North Devon

by Christina Hamlett

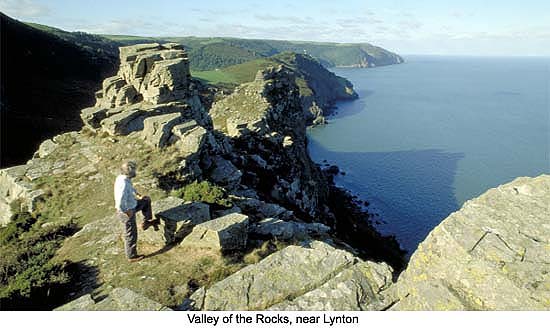

Like fraternal twins separated at birth, Lynton and Lynmouth have

grown up on either side of the Exmoor headland's wooded cliffs,

their personalities shaped by the respective influence of society

and sea. Both comprised of thatched cottages and quaint shops

reminiscent of a child's storybook, Lynton is the more

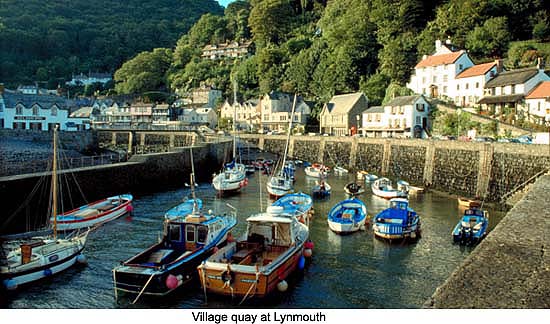

aristocratic and leisurely of the two. Lynmouth, situated below

in a gorge carved by the confluence of two rivers, is an

unabashed fishermen's village, teeming with an energy little

changed from that of its ancestors over a century ago. The

combined population of these two villages has grown very little

as well, in spite of the attractive draw of their location,

climate and the surrounding natural beauty of Exmoor National

Park.

To really appreciate the appeal of the North Devon Coast,

however, one needs to understand that the region never

aggressively positioned itself as part of mainstream England and,

thus, failed to attract a rash of greedy nobles who not only

might have run things differently but might have attracted

enemies in the process. Its actual origins date back to the

Neolithic and Bronze Age, a backdrop that's easy to picture as

you wend your way along the rocky coastal trails. Prehistoric

artifacts, tools and fossils are not an uncommon sight in the

area's historical museums, as are the ruins and smattering of

henges left behind by Romans, Normans and Saxons. Geographically

undesirable in terms of a power base, it enjoyed the advantage of

being left alone while the rest of the world pretty much went on

without it. The common folk who migrated here during the

Dark Ages were primarily just trying to find warmer temperatures

to do their farming, including the modest harvesting of grapes

for wine. Distrustful of strangers coming in and upsetting their

copasetic status quo, the impression they projected was that

those who planned to take up residence might not necessarily be

welcomed with open arms. As insular a community as they tried to

maintain, however, it was no protection against the spread of

plague, the decline of a woefully limited economy and the

pernicious tricks of Mother Nature. A succession of brutal

winters, droughts and even an earthquake in nearby Barnstaple in

the late 1600's left many starting to think that maybe shooing

away the tourists hadn't been such a good idea, especially in the

unbidden absence of healthy, able-bodied locals to do the

work.

It was the advent of the Napoleonic Wars that finally inspired

them to warm up to the idea of tourism as a way to generate the

much needed capital to keep their villages humming. Fearful of

traveling to Europe and yet anxious to slip away from some needed

R&R, English travelers on holiday made the discovery that

northern Devon had all the charm and amenities of the continent

but was secluded enough to sidestep any physical danger. To the

surprise of the locals, Lynton and Lynmouth quickly became a

retreat for painters, musicians, poets and writers seeking a

tranquil setting to exercise one's muse. With the arrival of

luminaries such as Samuel Coleridge, William Wordsworth and Percy

Shelley, it soon grew apparent that more inns and eateries were

needed to accommodate the favorable word of mouth publicity being

spread. So competitive was the inn trade that telescopes and

runners were put to use in order to claim dibs on the latest

arrivals, a humorous scenario that conjures the more modern image

of what happens when a prospective buyer steps onto the lot of a

car dealership.

Nicknamed "Little Switzerland," the villages retained

their popularity as a sequestered resort through the Victorian

era, an influence reflected in the number of tea rooms, vintage

hotel furnishings, and museums that feature memorabilia and

photos from the turn of the century. Visitors can also marvel at

the water-powered Cliff Railway installed in the 1890's to

facilitate easy travel between the two towns.

Our own discovery of Lynton and Lynmouth was purely the product

of accident. Literally. A multi-car collision on the A-39 west

of Minehead threatened a delay that put us at the vexing midpoint

of being too far away from our intended destination as well as

too far just to turn around and return home. Although we had

packed for an overnight stay, the impending approach of sundown

and our lack of a reservation also meant that we might be

deprived of a room for the night. Given that two out of three of

us consider "roughing it" the condition of not being

able to plug in a blow dryer and a curling iron, we outvoted our

male companion and insisted on taking the next available

turn-off.

Our spontaneity was rewarded not only with a modestly priced inn

(plus full breakfast) on the main street of Lynmouth but

enthusiastic recommendations for dining and sightseeing as well.

We also had the luck of arriving before the Memorial Hall had

closed its doors for the day, providing us with a harsh look at

how the forces of Mother Nature nearly erased all evidence of

Lynmouth's existence from the map.

The exhibition hall, built to commemorate those who lost their

lives, features a gallery of photographs and artifacts from a

violent summer storm and flood in 1952 that sent over a hundred

thousand tons of water, boulders, mud and debris crashing through

the village streets. The combined forces of the East and West

Lyn Rivers were enough to topple houses and shops in their path,

uproot entire groves of trees, and smash every fishing boat that

was moored in the harbor. Repair of the destruction and the

implementation of measures to ensure it would never happen again

took nearly four years to complete. Such tragedies, of course,

are never without the emergence of unsung heroes and the exhibit

is generous in its praise of those who opened their hearts, their

homes and their wallets in the aftermath of the flood's

devastating effects.

Acts of bravery, however, are no stranger to the seafaring

residents of Lynmouth. In 1899, a cargo ship called The Forrest

Hall was caught in a storm in the Bristol Channel off the Devon

coast. When it became apparent that the conditions were too

dangerous to try to undertake a rescue effort from Lynmouth

harbor, a group of 20 men and team of 18 horses proceeded to drag

a 3-ton lifeboat a distance of 14 miles (all hilly and in the

dark) where it could be safely launched from another port. Even

more remarkable than the fact that The Forrest Hall and all of

her crew were saved is that this nighttime endeavor lacked the

modern advantages of ship-to-shore communications. Sans any

contact with The Forrest Hall for a period of over 15 hours, the

Lynmouth volunteers had no idea if the battered ship would even

be within sight by the time they reached the docks at Porlock

early the following morning.

The nautical themes of the region are repeated in abundance in

houses and inns that once knew the likes of sea captains and

smugglers. At Watersmeet House, a Lynmouth fishing lodge dating

from the 1830's, visitors can enjoy exhibits and a spot of tea.

Now operated by the National Trust, Watersmeet is open daily from

April to October during the hours of 10:30 and 4:30.

Save time as well for a tour of Town Hall. Its design,

construction and ornamentation were financed by Sir George

Newnes, a wealthy entrepreneur whose credits in publishing

included the adventures of Sherlock Holmes and whose enthusiasm

as a visionary of better transportation between the twin villages

prompted the installation of the aforementioned Cliff Railway.

By the way, if your holiday happens to fall on the first Saturday

of the month, you won't want to miss the farmers market and

crafts fair which opens at 10 sharp at Town Hall. This can then

be followed by a brisk hike up to Hollerday Hill. Newnes was so

fond of his adopted villages that he built himself a manor house

up here with an enviable view. Although the estate was lost to a

fire almost a hundred years ago, the woods and trails now

occupying the site not only provide great exercise but panoramic

photo shoots, too, including a view of the coast of Wales across

the channel.

Another must-see while you're in the area is the Lyn and Exmoor

Museum on Market Street in Lynton. In addition to its collection

of Stone Age relics, this vintage building houses an extensive

display of farm tools and seafaring equipment from the past two

centuries and a Victorian dollhouse that will make you wish you

could shrink yourself down to fit through the doorway.

For outdoor enthusiasts, of course, Exmoor has more than just

cliffside hiking to commend it. Sport fishing and boating have

become popular draws, as are bicycling, horseback riding, and

even lessons in the Medieval art of falconry.

Are there any train-lovers in your group? One of Sir Newnes'

other bold ventures was to establish a railroad system in 1898

that would link Lynton with Barnstaple. Although it didn't

succeed quite to financial expectations during his lifetime and

subsequently became defunct, there was still sufficient regional

interest to keep Newnes' notion rolling until the 21st century.

Passenger trains are once more running between the two towns

during the hours of 11 and 4, offering a leisurely venue in which

to view the Exmoor countryside. Make sure you acquire a copy of

the timetable first, though, as its service tends to be erratic

during the non-summer months.

Speaking of Barnstaple, its proximity to Lynton and Lynmouth

makes it a value added stop on your English vacation. Situated

on the River Taw, Barnstaple's Saxon origins date back to 930

A.D. where its highest and best use at the time was as the first

line of defense against marauding Danes. It also has the

distinction of being the oldest borough in Great Britain, an

honor that still gets frequent mention amongst its contemporary

citizenry in taverns and shops.

Never a town to back down from a grand adventure (or a good

fight), local lore has it that Barnstaple ships were quick to

join the fray against the Spanish Armada in 1588 as well as

outfit merchants who were in search of fortune in that "New

World" everyone was talking about. Its emergence as a

lively center of trade and commercial activity is still seen

today in its eclectic assemblage of shops, farmers markets, art

galleries and museums. Barnstaple also offers a self-guided

historical tour that immediately reminded all three of us of

Boston's Freedom Trail back home. Named the Heritage Trail, this

walking tour covers 16 landmarks pertinent to the town's history

and development. In addition, the town's Heritage Center located

on Queen Anne's Walk is a multi-media exhibition hall that offers

something of interest for any age group.

Time permitting, you're not that far from the town of Arlington

and a must-see tour of the Arlington Court Estate. This Regency

era manor house and surrounding gardens was a private residence

until almost 1950. While romantics will enjoy an authentic

carriage ride around the grounds, younger members of the family

will squeal their heads off at something one wouldn't expect to

find at so elegant an address. Let's just say that the former

owner didn't keep bats in her belfry; they found a much more

hospitable environment down in the basement.

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Former actress and director Christina Hamlett is an award-winning author, instructor and script coverage consultant for the independent film industry. Her credits to date include 21 books, 115 plays and musicals, 4 optioned feature films, and columns that appear throughout the world. She and her husband reside in Pasadena, California.

Article © 2006 Christina Hamlett

Photos courtesy of Britainonview.com

|