Jorvik: The Viking City of York

by Brenda Ralph Lewis

When the Vikings conquered York, in 866 AD, the city already possessed a long urban history. Founded by the Romans in 71 AD as a fortress town, York fulfilled this purpose for more than 350 years, until the end of Roman rule in Britain. Another 450 years of Anglo-Saxon York followed, during which time the town was a major royal, ecclesiastical and trading centre. Consequently, when the Vikings took over, they found many urban features ready-made for them. The massive Roman walls, for instance, were so solidly built that even after four centuries, the Vikings were able to use them as part of the defences for their own York -- or Jorvik, as they named it.

Viking Raiders, City Planners

In Jorvik, the Vikings -- first known in Britain as marauding raiders -- soon demonstrated that they had other, more civilized talents. The city they developed became a prime commercial, trading and residential centre and the capital of the the Norse Kingdom of York. It appears that the streets had metalled surfaces, and the Vikings also created a major crossing over the River Ouse, with a main street, Micklegate ('the great street') leading to it; the crossing remains in place to this day.

In Jorvik, the Vikings -- first known in Britain as marauding raiders -- soon demonstrated that they had other, more civilized talents. The city they developed became a prime commercial, trading and residential centre and the capital of the the Norse Kingdom of York. It appears that the streets had metalled surfaces, and the Vikings also created a major crossing over the River Ouse, with a main street, Micklegate ('the great street') leading to it; the crossing remains in place to this day.

The layout of Jorvik set a new standard in urban street planning and building. Since 1976, the York Archaeological Trust has excavated areas at 16-22 Coppergate, 58-59 Skeldergate, 6-8 Pavement, the space between 25-27 High Ousegate and 5-7 Coppergate, and stretches of Walmgate. These sites have revealed a series of building plots complete with backyard wells and cesspits. The houses of Jorvik were of the post-and-wattle type -- so-called because their main wall post or roof supports were interwoven horizontally with wattlework rods of hazel, willow or oak. The boundaries were delineated by a wattlework fences and wattlework panels were laid down to make narrow pathways.

House construction in Jorvik was generally standardised. The plots were a regular 5.5 metres or thereabouts in width. The rectangular houses typically measured 4.44 metres wide by about 14.85 metres in length, with earthen floors. Sometimes, wattle-lined soil-filled benches lined the walls, with seats covered with soft plants. A clay hearth measuring about 1.82 metres 1.2 metres lined in stone marked the centre of each house. In some houses, the position of the hearth was indicated by the traces of ash and areas burned red; others, however, have been found surrounded by old Roman tiles or limestone rubble. The wood and thatch structure of houses inevitably made the hearth a fire hazard, but a presumed lack of windows meant that it also served as a principle source of indoor lighting. Supplementary lighting probably came from stone or pottery lamps with wicks that burned oil or fat.

The earlier Viking houses in Jorvik had only one storey -- the wattlework walls were not strong enough to support an upper floor -- with, most likely, a thatched roof supported by the more substantial uprights. However, four houses excavated at Coppergate dating from the late 10th century revealed an extra storey underground. This consisted of a basement sunk to a depth of about 1.82 metres, approached by a stone-lined corridor and furnished with strong oak beams, posts and planks. Excavations in Dyflin have shown that similar buildings were constructed there, though at a rather later date.

Viking Life Preserved

A particularly fortunate feature of Jorvik -- at least for archaeologists -- was a damp environment that favoured the preservation of ancient remains. Lying beneath the layers built up by time, Jorvik survived well in oxygen-free, organic-rich soils that protected vulnerable materials such as wood, leather and cloth from the decay caused by bacteria. Even insects and other animal remains, seeds, pollen, fruit-pips, twigs, plants, thatch, wood chips, straw, heather, molluscs or parasites have been found more or less intact despite the passage of a thousand years.

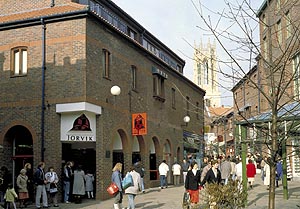

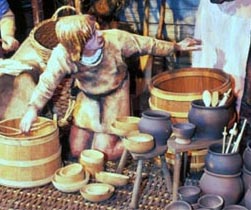

Together with more durable relics of stone, metal, bone and pottery, these discoveries have made it possible for the Jorvik Centre in Coppergate to create a detailed picture of the life in early medieval times. The Centre's pictorial reconstructions and tableaux are all based on sound archaeological evidence, right down to the lichen the Vikings used to dye cloth and the precise weave of the clothes and socks they wore. One of the most complete and rare finds at Jorvik was a 10th century sock, knitted from wool on a single needle or nålebinding. In addition, experts have recreated the facial appearance of the town's inhabitants based upon skulls retrieved from the cemetery near the site where the Viking Age cathedral may have stood.

Together with more durable relics of stone, metal, bone and pottery, these discoveries have made it possible for the Jorvik Centre in Coppergate to create a detailed picture of the life in early medieval times. The Centre's pictorial reconstructions and tableaux are all based on sound archaeological evidence, right down to the lichen the Vikings used to dye cloth and the precise weave of the clothes and socks they wore. One of the most complete and rare finds at Jorvik was a 10th century sock, knitted from wool on a single needle or nålebinding. In addition, experts have recreated the facial appearance of the town's inhabitants based upon skulls retrieved from the cemetery near the site where the Viking Age cathedral may have stood.

Since the houses were used as both living quarters and workshops, the same sites served to build a picture of working as well as domestic life. Quernstones for grinding corn to make flour have been found, together with ancient cereal grains. Other items of the Viking diet, such as bran, herbs, vegetables, fruits, eggs, have been discovered through seeds, pips and eggshells, as well as the usual fish and meat, which included goose, something of a delicacy.

Further proof of the Viking diet comes from the excrement left behind in privies situated in the yards behind the houses. Analysis also revealed that the inhabitants of Jorvik were prone to intestinal parasites -- inevitable when backyards housed waste pits in close proximity to drinking water wells, all in the same area used to house animals with their litter and manure.

A considerable number of tools have been excavated in houses at Jorvik, including a fine set of woodworking tools -- drawknife, chisel axehead, auger. Other finds include sickles, sharpening stones and knives, jewelry moulds, the cores of wooden bowls, scraps of cloth, offcuts of leather, bucket staves. All this provides a picture of a busy community, and a skilful one. Baked clay loom weights indicated the production of textiles. Combs, pins and whorls for spindles were made by bone- and antler-workers. Blacksmiths used tin or lead and copper alloys to plate iron, and also worked in gold and silver.

Elsewhere, pieces of leather waste and the discovery of a cobbler's wooden last indicate the making and repairing of shoes, belts and scabbards, many of which were ornately decorated. Traces of wool and bits of fleece give evidence of wool processing and fleece imports, and jewelry scrap showed that decorative pins and brooches were made in Jorvik, together with many items mass-produced for quick, cheap sale. These included buckles and brooches made of lead, gold earrings, glass beads decorated with gold leaf, necklaces of jet and glass beads, and copper alloy and bone pins used as clasps for clothing. More prosaically, iron was used in the manufacture of cooking pots, frying pans, padlocks and keys, while wood was used for bowls and spoons.

Elsewhere, pieces of leather waste and the discovery of a cobbler's wooden last indicate the making and repairing of shoes, belts and scabbards, many of which were ornately decorated. Traces of wool and bits of fleece give evidence of wool processing and fleece imports, and jewelry scrap showed that decorative pins and brooches were made in Jorvik, together with many items mass-produced for quick, cheap sale. These included buckles and brooches made of lead, gold earrings, glass beads decorated with gold leaf, necklaces of jet and glass beads, and copper alloy and bone pins used as clasps for clothing. More prosaically, iron was used in the manufacture of cooking pots, frying pans, padlocks and keys, while wood was used for bowls and spoons.

From "Raid" to "Trade"

A wide range of exotic goods traveled up the River Ouse by ship to land at the port of Jorvik, including amber from Scandinaiva or the Baltic lands, which was made into pendants and rings. The remains of such imports suggest a wide-ranging network of trading contacts, not only to the ancestral homelands in Scandinavia and the rich trading port of Dublin, but as far afield as the Mediterranean, the Middle East, the Indian Ocean, Asian Russia, the Byzantine Empire and China.

A considerable amount of silk -- 23 separate fragments -- has been found at 16-22 Coppergate, suggesting extended trade routes that ran from China, the original site of silk manufacture. Other indications of trade include an Islamic coin from Samarkand (Uzbekistan), which was notable even though it proved to be a 10th century forgery. Cargoes of wine and quernstones made of lava, whetstones, pottery, soapstone cooking vessels, furs and dyestuffs came into Jorvik from Scandinavia and northern Europe, including Pingsdorf pottery from the German Rhineland.

Jorvik also took in goods and materials from the area immediately surrounding the town. Several villages, some of Anglo-Saxon origin and some of Viking origin, surrounded Jorvik. One, Copmanthorpe -- to the south of Jorvik -- revealed its nature in its name: 'outlying farmstead or hamlet belonging to the merchants'. It is likely that the merchants of Copmanthorpe and other riverside villages were the first to receive goods from the trading vessels sailing up the River Ouse and then took them to Jorvik for sale in the markets.

Jorvik also took in goods and materials from the area immediately surrounding the town. Several villages, some of Anglo-Saxon origin and some of Viking origin, surrounded Jorvik. One, Copmanthorpe -- to the south of Jorvik -- revealed its nature in its name: 'outlying farmstead or hamlet belonging to the merchants'. It is likely that the merchants of Copmanthorpe and other riverside villages were the first to receive goods from the trading vessels sailing up the River Ouse and then took them to Jorvik for sale in the markets.

Local manufactures as well as imports were on sale, too. Industry in Jorvik was sufficiently well established for individual streets to be identified with certain trades -- Coppergate as the centre of carpentry and Skeldergate as the street of the shield-makers. Among them were the makers of decorative metalwork and a glass bead-making industry. Blue soda glass and high-lead green or black glass were used in the manufacture of beads. The soda glass was most probably gleaned from small quantities of scrap left behind by the Romans. It appears to have been melted down on rough ceramic disks, scraped off, then formed into beads. High-lead glass has been less conclusively traced, but it has been suggested that it was used as a form of iron, to smooth off linen.

Night Life and After-Life

The Jorvik finds also reveal the entertainments that occupied the Vikings' spare time, apart from the traditional recital of the great sagas. The Vikings had a game called hnefatafl, played with pieces of bone and stone that were among the finds at Jorvik. Dice made of bone and gaming counters in profusion have also been uncovered. Viking musical instruments include a set of boxwood pan pipes, a flute made from the leg-bone of a swan and a tuning peg decorated with animal heads for some instrument yet to be discovered .

The excavation of Jorvik has cast light, too, on Viking religious beliefs, which appear to have been on the cusp, as it were, between Christianity and their own ancestral pagan creed. Although numerous churches were built at Jorvik, Viking pagan beliefs persisted for a century or more after their arrival from Scandinavia. This is illustrated by a die, dated about 920-927 AD, which was used for minting St. Peter's Pence (a tax paid to the papacy in Rome). The die showed both the symbol of the Cross and the hammer of Thor, the Viking god of thunder. Similarly, a coin of Olaf Guthfrithsson, King of York between 939 AD and 941 AD, carried a bird emblem, possibly a raven, which was a symbol of Odin, principal god of the Norse pantheon. In addition, the coin was inscribed not in the customary Latin, but in Old Norse. The excavations at Jorvik have also unearthed a 10th-century stone grave marker, probably originating at All Saints' Church nearby, that carries an interlaced animal design more typical of pagan than of early Christian practice.

As a Viking city and kingdom, York had a surprisingly short life. It was absorbed into the rest of England in less than 90 years. Around 954 AD, the Northumbrians drove out the last king, the flamboyantly named Eirik Bloodaxe, who was killed in battle soon afterwards. Bloodaxe, reputedly a fratricide seven times over, was more typical of the Vikings in their earlier, marauding guise. However, the great value of the excavations in York has been to reveal another, less familiar image -- the Vikings as civic organisers, planners, architects, roadmakers, artisans, artists, traders and just ordinary people, leading ordinary lives.

Related Articles:

- The Treasures of York, by Pearl Harris

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/towns/york.shtml

- Uncovering the Archaeological Bounty of York, by Sara Polsky

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/towns/yorkdig.shtml

- York Timeline

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/towns/yorktime.shtml

- The Ghosts of York, by Jillian Schedneck

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/history/ghosts.shtml

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Brenda Ralph Lewis has published more than 100 books, most upon historical topics, including Reader's Digest's Kings and Queens of England and a biography of Winston Churchill. She has traveled extensively in Europe, Asia, South and Central America, the US, and Canada. She says that she planned to become a writer since the age of eight, and though she studied music for many years, "writing won out in the end." Her great hobby is philately. She lives with her husband and son in "the very historic county of Buckinghamshire."

Article © 2005 Brenda Ralph Lewis

Photos © Britainonview.com

|