Exeter - The Cathedral City

by Clayton Trapp

Exeter is dominated, historically and geographically, by the

Cathedral of St Peter. The cathedral is elevated on a hill and

so can be seen from virtually anywhere for miles around. It

pokes out from every street corner and, because the city's street

plan has evolved in a rather entropic and angular manner, gives

the illusion of moving around.

The cathedral is among the three or four most famous

in the kingdom and few visitors leave town without the full tour,

and catching their breath a few times at the sheer beauty and

otherworldly presence of the structure. Unlike other attractions

of its magnitude, I've never heard anyone express disappointment

upon experiencing Exeter's Cathedral of St Peter. The cathedral is among the three or four most famous

in the kingdom and few visitors leave town without the full tour,

and catching their breath a few times at the sheer beauty and

otherworldly presence of the structure. Unlike other attractions

of its magnitude, I've never heard anyone express disappointment

upon experiencing Exeter's Cathedral of St Peter.

Unfortunately many visitors focus on the cathedral at the expense

of everything else. Exeter has the wealth of history that one

would expect from a jewel at various times times plucked, or at

least attacked, by the Romans, Saxons, Normans, Vikings, Nazis

and a host of internal revolutionary groups during and after the

Wars of the Roses.

Historians generally agree that a settlement in what is now

Exeter predates the Roman invasion. Ancient rumour holds that

Exeter's famous walls, much of which still stand, were

instrumental in repelling the Roman Emperor Vespasian in the

first century. Thus thwarted, Vespasian then turned his

attentions more successfully on Jerusalem.

Historians tend toward the opinion that Exeter's walls were not

built until the end of the second century, by the Romans who

played a key role in establishing Exeter by setting up a garrison

on the hill where the cathedral now stands (around 50 AD). Thus

satiated, and after naming the town Isca, Vespasian moved on.

In either event, Vespasian was hardly the last of the invaders,

and the walls saw plenty of action. By the 20th century,

however, they were obsolete as Nazi bombers simply flew over

them, dropping loads that demolished High Street and clipped the

cathedral.

Nazi destruction gave rise to a post-war architectural

renaissance. Today new mixes with old as neon cafés and

surf shops mingle with ancient pubs and cobblestone in the

shadows of the cathedral and protective walls. A new shopping

development in Princesshay will add a space age Californian

sensibility to the aesthetic mélange of the downtown area.

As an added bonus for the traveller, everything you want to see

is within easy walking distance.

The Cathedral

However spectacular the Princesshay development may

turn out to be, no pseudo-mall is ever going to replace the

Cathedral of St Peter in the hearts or minds of the locals or

visitors. The cathedral has stood for nearly one thousand years

and enjoys beauty and spiritual qualities that would make it

appealing even if it had been built yesterday. It is a structure

of those qualities that are simply impossible to relate in the

absence of experiencing them first hand. However spectacular the Princesshay development may

turn out to be, no pseudo-mall is ever going to replace the

Cathedral of St Peter in the hearts or minds of the locals or

visitors. The cathedral has stood for nearly one thousand years

and enjoys beauty and spiritual qualities that would make it

appealing even if it had been built yesterday. It is a structure

of those qualities that are simply impossible to relate in the

absence of experiencing them first hand.

Christians worshipped near the site of the cathedral during Roman

times, and a monastery (where St Boniface was schooled) was built

around on the grounds around 1040. A decade later Edward the

Confessor transferred the see of Crediton to Exeter, thereby

setting off speculation as to the adequacy of the monastery for

its expanded role.

The third Bishop of Exeter, William Warelwast (nephew of William

the Conqueror, who had taken Exeter in 1068) quashed the

speculants by beginning work on a mighty cathedral to replace the

monastery, around 1110. Warelwast's vision took fifty years to

realize, but satisfied the powers that be for only about 200

years. In 1260 the cathedral was demolished, with the exception

of its two Norman towers, with the cathedral as we now know it

taking shape over the succeeding 130 years.

Warelwast's contribution should not be quickly dismissed. The

Norman towers -- St Paul's on the north and St John's to the

south -- define the cathedral from a distance, and are certainly

among the most inspiring aspects of the cathedral. St John's

tower also now houses a peal of 14 bells, and St Paul's the

extraordinary four ton bell donated by Bishop Peter Courtenay in

1484. It is Courtenay's bell that still marks the hour, sending

reverberations down the River Exe and off into the

countryside.

A visitor's impression of the majestic towers is immediately

confirmed by a few minutes at the west front of the cathedral.

It is here that visitors and parishioners enter the church, but

no one can ever go straight in! The stone work is simply

incredible, and though some has deteriorated slightly to the

years (the west front assumed its current glory during the

mid-14th century) what remains is really too wonderful to

imagine.

Figures stand out on the west front like a roll call from heaven

itself. The top tier of 28 ecclesiastical figures finds Jesus

fifteenth from the left. William the Conqueror occupies a place

of honour in the middle row, dedicated to kings, and a bottom row

of angels -- many playing musical instruments -- support their

earthly allies. Sadly the key to identifying all of the figures

has apparently been lost.

Entering the cathedral is no less inspiring than standing

outside. The longest unbroken stretch (68 feet, 21 meters) of

Gothic vaulting in the world stretches above the nave floor, to

which it is connected by thirty 14th century columns of Purbeck

marble. The vaulting is complemented by decorative pieces

depicting biblical and historical scenes, perhaps the most

striking of which is the murder of Thomas Becket in Canterbury

Cathedral (one of Exeter's few "rival cathedrals" in

terms of tourism).

Cathedral aficionados are invariably impressed by the minstrel's

gallery on the south side of the nave, where twelve sculpted

angels can be found playing 14th century musical instruments.

Sadly one of the angels lost their instrument at some point along

the way, but it's difficult to imagine that such a thing would

amount to much of a setback to an angel. On Christmas Day the

church choir sings from a room behind the gallery, reminding the

faithful of our potential to follow the example of the

sacred.

Entire books have been written on the cathedral but no

consideration could have any semblance of authority without

mentioning the 15th century astrological clock that depicts the

orbit of the sun (represented as a fleur-de-lys) and moon around

the earth. The clock also tells time, somewhat more accurately

than it demonstrates the movements of celestial bodies, and is

said to have inspired the lyric poem "Hickory Dickory

Dock."

In fact, for all of the cathedral's historic grandeur, elements

of the humorous and bizarre abound. One of the 13th century

misericords, found below the choir stalls, is, for example,

decorated with an elephant. That might be notable in its own

right, but this particular elephant is the work of a master

craftsman whose experience was no doubt broad but did not include

ever personally engaging in any way with an elephant. The result

is a profoundly expressive creature with tusks, but one who also

sports expansive hooves of a nature to make any team of

racehorses jealous.

A visit to the cathedral is certain to be a dramatic event under

any weather or circumstance. The power of the cathedral is such

that any storm could only play a supporting role, and insider's

swear by sensations brought on by the falling sun's illumination

filtered through the great west window onto the cathedral's

pillars, vaults and tombs.

Exeter is said to be Britain's most haunted city, and such lore

couldn't possibly be complete without such goings-on in and

around the cathedral. The ghost of a past caretaker, whose love

of the cathedral was nearly legendary in itself, has been

witnessed in one of the chapels on several occasions. On warm

July evenings the ghost of a nun has been seen floating about the

south wall of the nave, several times over the years.

Finally it must be said that Exeter's cathedral is a

working church. The pious, or curious, can select from five

services on any Sunday, four services on weekdays, and a number

of special events throughout the year. Finally it must be said that Exeter's cathedral is a

working church. The pious, or curious, can select from five

services on any Sunday, four services on weekdays, and a number

of special events throughout the year.

The area surrounding the cathedral is historic in its own,

somewhat different, right. Cathedral Close wouldn't be a bad

subject of an essay, and the truth is that the saltiest dogs of

the seagoing epoch found their pleasure in the area within a

stone's throw of the Norman towers. The Close was also the point

of departure for Jonathan Harker's trip to Transylvania in Bram

Stoker's "Dracula." [For a related article, see Whitby: Town of Voyagers and

Vampires, by Jane Gilbert.]

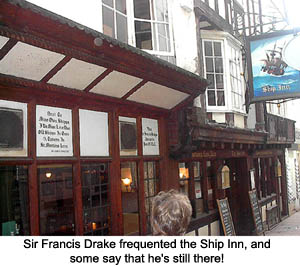

No less than Sir Francis Drake declared the nearby Ship Inn to be

his favourite place on earth, with the obvious exception of his

own ship. It is said that Sir Drake enjoyed the environs of the

Ship Inn to such a degree that management determined that his

visits would be welcome only on those occasions that the

legendary explorer was accompanied by "a responsible

person." At the time Drake was said to be in something akin

to agreement, but in the intervening years the great man's ghost

has been blamed for a great deal of havoc at the pub including

pushing people down a flight of stairs.

The Quay

About ten minutes by foot from the cathedral, Exeter's quay is

hardly comparable to New York's harbor, or even Seaport Village

in San Diego, and therein lies much of its charm. The quay is a

clever echo of an age gone past, replete with nice food and shops

and no small amount of history if you look upon the scene with

proper eyes.

In the early days, going back to Roman times, trade was conducted

on the River Exe. The river is not particularly immense,

however, and so goods had to be transferred on the wider portions

of the river, which weren't as far inland as merchants would have

liked. To make matters even more difficult a series of Earls of

Devon conducted economic battles with the city in efforts to

collect taxes.

The Earls were outraged that commerce flowed even as smoothly as

it did -- instead of ships importing needed goods, they saw taxes

just flowing by and getting away. A weir was built, impeding

traffic on the Exe but ensuring taxation.

For more than one hundred years (1335-1461) the Courtenays

(Earls) controlled commerce, and everything else, in the area,

unchallenged as favourites of the monarchy. In 1461, however,

Thomas Courtenay apparently misplayed a point, and was beheaded

by the king.

The loyal citizens of Exeter immediately petitioned the crown for

their rights to fish in and navigate the waters of the Exe, but

the king was apparently too busy for such trifles and failed to

respond. Nothing changed.

The wool trade became Exeter's primary industry and the

Courtenay's taxed it enthusiastically. Perhaps the Courtenays

were a restless dynasty, but whatever the case Henry Courtenay

was beheaded for treason in 1539.

Now

troubled by the necessity of having had to behead two Courtenay's

in only 70 years, the king finally granted the city permission to

make the river more easily navigable again. Unfortunately the

weir had created an imposing silt buildup. Now

troubled by the necessity of having had to behead two Courtenay's

in only 70 years, the king finally granted the city permission to

make the river more easily navigable again. Unfortunately the

weir had created an imposing silt buildup.

The decision was made to build a canal, and Exeter's churches

were among the leading economic contributors. Just when things

looked to be going smoothly Exeter was shaken to its foundations,

and put under siege, during the Prayer Book Revolt of 1549.

Fortunately the prayer book disagreements were resolved after a

scant fourteen years, and the minds of the day again turned their

attention to the canal.

The canal leading to the quay was the first in England to use

pound locks, and opened to shipping in 1566. The world was a

simpler place then, and the great ships weighed anchor at sea,

sending lighter boats filled with goods through the canal,

typically pulled by hand or horse. Taxes on trade through the

canal were sometimes levied, but often forgotten.

By the mid 17th century the canal was in disrepair and Exeter's

increasing population was stretching the water supply in all the

usual ways. Dramatic action was obviously needed, and Richard

Hurd of Cardiff stepped forward to dredge the canal for the

rather reasonable fee of £100. Hurd's efforts were

accompanied by the creation of a canal extension making it

possible for larger ships (to 60 tons) to take advantage of the

trade opportunities offered by the quay.

Of course progress moved quickly, and a mere fifty years later a

decision was made to further enlarge the canal. The major

project was entrusted to an engineer, William Bayley, who

promptly made off with the loot, bringing work to a decidedly

sudden stop. Dejected but not defeated, the Chamber raised money

for the project through loans and the canal was once again

elevated to cutting-edge status (now 300 ton ships were arriving

at the quay).

Sadly, the shipbuilders just kept making them larger and larger

and by the mid 19th century the quay had been effectively

relegated to historical remnant status. Its final gasps were in

terms of flooding, and a flood of ship owners presenting bills

for their losses to local government.

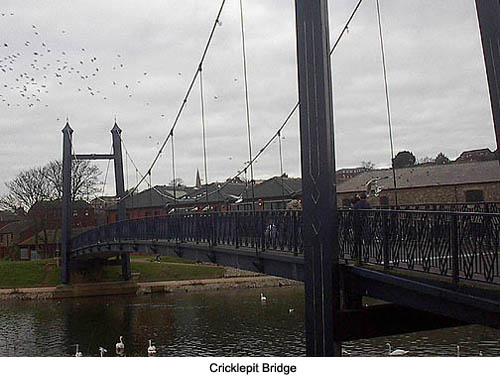

Today the quay and canal remain, dotted with pub umbrellas and

gift shops. The area picks up in the summer but is never

oppressively crowded. Bridges (including the venerable

Cricklepit Bridge) and wooded areas make the canal an excellent

area for walks, Alternately, canoes are available for hire.

The single funnest thing to do at the quay, though, is to take a

ride on Butt's Ferry. The ferry is named after George Butt, who

valiantly battled in the 1970s against the City Council, who had

the lack of vision to consider the ferry too expensive to operate

(passage costs approximately the same amount as a brief local

telephone call).

In the council's defense it must be admitted that the ferry

crosses the canal at a point where... well, you could easily

throw a rock across it, or swim across in a matter of two or

three minutes, but that isn't the point. It's as fun as it is

silly.

The ferry (summertime only) operates through a rather unique

system whereby the ferryman propels the miniature barge, holding

perhaps four passengers, across the canal by means of locomotion

generated by his pulling along a wire linking the two sides of

the canal. Fewer ferries get lost that way, you see, and the

petrol bill remains lower.

The Guildhall

Exeter's Guildhall is the oldest in the kingdom, dating

back to 1160. Of course improvements have been made since then

and so it's unlikely that any of the Guildhall that you see on

High Street dates further back than 1330. The four granite

pillars of the Tudor Portico (installed for a reasonable

£782), supporting the Mayor's Parlour (previously the

chapel), are recent additions that date back a mere 400

years. Exeter's Guildhall is the oldest in the kingdom, dating

back to 1160. Of course improvements have been made since then

and so it's unlikely that any of the Guildhall that you see on

High Street dates further back than 1330. The four granite

pillars of the Tudor Portico (installed for a reasonable

£782), supporting the Mayor's Parlour (previously the

chapel), are recent additions that date back a mere 400

years.

The Guildhall was the center of commerce in the early days. The

council met in the Great Chamber, and four special benches marked

off an area designated as the court. Anyone, or any business

taking place, within the confines of the benches was considered

as being, or done, "in court."

By Tudor times the Guildhall had evolved from being strictly a

commercial center, to include entertainment. The King's Players,

or Queen's Players, came through with an eagerly awaited play

each year, and numerous other plays and musical events kept the

mood of the city festive.

The Guildhall remained the hub of much local government

bureaucracy, and as such couldn't help but be a focal point of

the Prayer Book Revolt of 1549. Proponents and opponents of the

new English-language book plotted and seethed, with defections

celebrated and lamented, until the Guildhall literally came under

siege in the midst of bureaucratic mutiny. In fairness to both

sides precious little harm came to the Guildhall, perhaps due to

the plethora of prayers proceeding from both camps of

combatants.

The Guildhall still houses bureaucrats, music, and theatre, and a

museum has been added. Highlights of the museum include the

sword and hat of maintenance (rewards from King VII for Exeter's

loyalty in seeing off a challenge to the throne by a Dutchman,

Perkin Warbeck, with a penchant for claiming to be, among other

things, the bastard son of Richard III or alternately Edward IV's

nephew, the Earl of Warwick), and various chains and maces and

silver objects.

Against all odds there have been no recordings of ghostly

activities in the Guildhall proper. Next door, however, in the

building now housing Ernest Jones, Jewellers, a female ghost has

been known to rush towards patrons before suddenly vanishing,

repeatedly set off the fire alarm, and knock over items too

numerous to mention. This latter activity has earned the moniker

of "Exeter's Clumsiest Ghost."

On the south side the Guildhall is flanked by the Turk's Head, a

pub frequented by Charles Dickens in his day. It is said that

Dickens conceived the Fat Boy of Pickwick Papers, and

Martin Chuzzlewit, amid pints of ale consumed here. Visitors are

encouraged to try their own luck whilst imbibing in the

"Dickens Corner" of the pub.

The Underground Passages

Exeter's underground passages are proof positive that

you can never tell what succeeding generations are going to find

interesting. They were excavated beginning in the mid-12th

century for the entirely utilitarian purpose of simplifying work

on the city water system. In the years since they have been

linked with buried treasure, secret escape routes, subterranean

religious activity, and a ghost on a bicycle. Exeter's underground passages are proof positive that

you can never tell what succeeding generations are going to find

interesting. They were excavated beginning in the mid-12th

century for the entirely utilitarian purpose of simplifying work

on the city water system. In the years since they have been

linked with buried treasure, secret escape routes, subterranean

religious activity, and a ghost on a bicycle.

The history of a water system is rarely as exciting as an

underground passage, but the tale of Exeter's water supply is

hardly, um, dry. At one point the same workmen who created the

exquisite west front of Exeter's historic cathedral were

commended for their work and promptly sent underground to dig the

passages. Payment was slight, in accordance with the tradition

of the day, but included princely quantities of ale.

The underground passage system became expansive, and was

considered a source of vulnerability during the English Civil War

in 1642. Portions of the passages were blocked off and

subsequently collapsed. For more than ten years the entire

system was useless, but was repaired in 1655 with the cessation

of hostilities.

Exeter's rapidly increasing population (a whopping 15,000 by the

end of 1699) stretched the system, and led to the successful

search for alternate delivery systems.

Nonetheless, the venerable passage system continued to be part of

the solution until the cholera outbreak of 1832. Exeter's slums

were hardest hit, with hundreds dying during the first months of

the outbreak. To their credit local government responded quickly

and with all of the resources that they had, and when it became

apparent that the underground water system was a source of the

disease it was permanently shut down.

Today Exeter's underground sandstone passages present as

something considerably more dramatic than a water system. No

similar passages can be found in England, and they simply demand

all of the myths that have grown around them. The oldest

accessible parts of the passages date from the mid 14th century

and visitors are warned that vaulting can be low, floors uneven,

and passages constricted.

More to See...

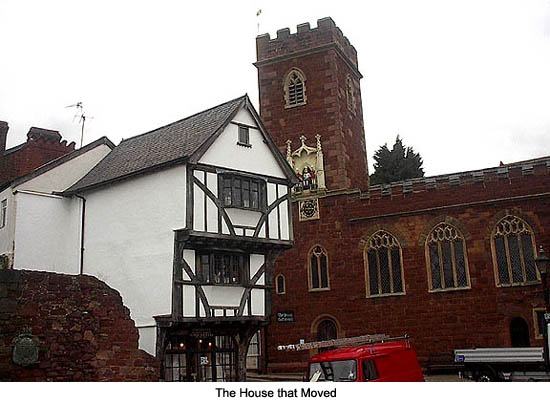

The House that Moved. Stepcote Hill. It's only a small

Tudor (1471) timber-framed house -- one room wide but three

stories high -- but Tuckers Hall created quite the international

sensation when it was threatened by road expansion in 1961. The

faithful rallied and the house was eventually put on rollers and

rolled to its current place of rest, a full 70 meters (75 yards)

from the original. Located approximately midway between the

cathedral and quay, just ask any local where to find "the

house that moved."

Mile End Cottage. Church Road, Alphington. Several

miles south of everything else you'd like to see in Exeter, but

well worth the trip for Charles Dickens fans. The beloved writer

rented the cottage primarily to keep his father from getting into

trouble in London, but after four years the elder Dickens tired

of the lack of temptation presented by the (then) countryside.

Charles Dickens visited his parents regularly at Mile End

Cottage, and wrote the opening chapters of "Nicholas

Nickleby" there. The landlady was the inspiration for the

character of Mrs Lupin the Blue Dragon in "Martin

Chuzzlewit. The cottage is now a private residence, but you're

welcome to read the plaque outside.

Best Place for a pint: The Royal Oak Public House. 68

Okehampton Street. (01392) 255665. Located a 15 minute walk and

just across the River Exe from the Cathedral, the Royal Oak is

one of those perfect old British pubs. The interior is warm and

wooden and bereft of pretense. The regulars are friendly, but

happy enough to leave you alone if you prefer. On sunny days you

can sip local Otter Ale on the deck overlooking the river,

lording over the procession of joggers and dogs along the

footpath below.

Best Place for dinner: The Old Times Wine Bar &

Restaurant. Little Castle Street. (01392) 477704. Located in an

alley, about three minutes walk from the Cathedral, the Old Times

offers a bar decorated in a highly spirited and eclectic manner

(lots of wood, a giant model airplane, old advertisements,

thousands of items), and outstanding pub food. Stilton Glazed

Garlic Mushrooms and the Bacon and Brie Ciabatta are recommended.

Upstairs things are a bit fancier without entirely losing the

casual feel, but still reasonably priced. The steaks are said to

be Exeter's best, and other options include Italian specialty

dishes and Hickory Ribs that make ordering automatic for my

wife.

Red Coat Guide Tours: (01392) 265203. Various guided

tours of Exeter (Medieval, Roman, Cathedral to Quay, Ghosts and

Legends, etc) are available free of charge, and year round. No

booking is required.

Related Articles:

- Exeter Timeline, by Darcy Lewis

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/towns/extime.shtml

- A Taste of Devon: Clotted Cream, Splits, Scrumpy and Gin, by Dawn Copeman

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/taste/taste06.shtml

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Clayton Trapp is the author of the novel Snap Once, a

series of children's books, and several nonfiction

works. He lives in Exeter with his wife, four

children, and a gloriously obstinate dog named Laural.

Article and photos © 2006 Clayton Trapp

(Top three photos courtesy of Britainonview.com)

|