Silbury Hill and West Kennet Long Barrow

by Moira Allen

Just south of Avebury, and generally considered part of the

overall Avebury temple "complex," stands Silbury Hill.

In a county full of prehistoric "mosts," Silbury Hill

is yet another: The tallest man-made prehistoric mound in Europe,

and one of the largest in the world. Rising like a shallow,

flat-topped cone from the fields, it stands 40 meters high and

covers about five acres, with a base 1640 feet in circumference.

Work on the mound began around 2660 BC, during the first week

of August -- a date determined by the discovery of winged ants

and certain types of seeds within the mound. This places the

beginning of construction right around the Celtic harvest

festival of Lughnasad or Lammas, which has led many to speculate

that the mound may be associated with harvest rituals. Another

factor contributing to this view is the fact that the mound

cannot be seen from Avebury until the crops in the intervening

fields have been harvested.

Experts aren't entirely in agreement on how the mound was built.

Some believe that it was built in three stages, starting with a

gravel core contained within a ring of stakes and sarsen

boulders. This core was then covered over with chalk and earth,

most of which was dug from the ditch that once surrounded the

mound. It's not clear whether this ditch was dug intentionally

(perhaps to be filled with water to form a sort of reflecting

pool), or whether it was simply a byproduct of the quest for

building material, as it was subsequently filled in. The final

phase of construction involved building six concentric terraces,

which were then filled in and smoothed over with more rubble and

chalk (which was by this time being brought from elsewhere). Only

one terrace remains, about 17 feet below the summit. In all,

more than 12 million cubic feet of chalk and earth went into the

building of the mound.

Originally the mound was thought to have been built in

concentric layers, like a cake (hence the terraces). Another

view, however, is that it was actually built in a spiraling

pattern, rising from the bottom to the top. Again, experts

disagree on why this might have been the case. Some believe that

the spiral indicates a ritual processional path to the top of the

mound; others believe that this was simply a much easier method

of construction than the layer-cake approach. Given that the

terraces of the mound were apparently smoothed over as

part of the original construction process, and not at some

later time, the second theory seems more likely; if the spiral

had been intended as a road, one would imagine that it would have

remained in use for a period of time before being covered over.

In fact, the mound does not appear to have been designed to have

been "climbed" at all; its smooth walls do not permit

one to simply walk up to the top, without carving a new pathway

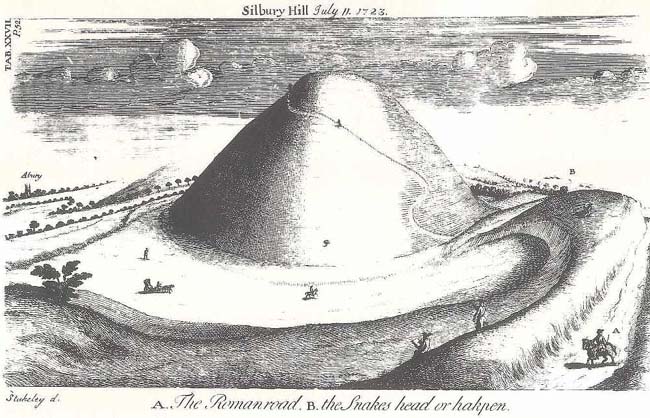

(which, based on drawings of the site by William Stukeley in his

18th-century book Abury - A Temple of the British Druids,

appears to have been done in later times). Quite possibly,

therefore, the mound was not built to be used, so much as

to be observed from another location.

As to the purpose of the mound, the only thing that theorists

can truly agree upon is that no one really knows. Theories

abound, linking the mound to fertility rituals, harvest rituals,

the Mother goddess, ley lines, and even "dragon lines"

(based on its resemblance to lung-mei mounds in China).

Local legend attributes the mound to the devil, who was planning

to dump a load of earth on nearby Marlborough but was prevented

by the priests at Avebury. In another version, it is a clever

cobbler who thwarts the devil. The cobbler was bringing home a

load of shoes to repair when Old Nick confronted him and asked,

"Old Cobbler, is it far to the town of Marlborough?"

Perhaps noting that his questioner's feet wouldn't have fit into

any of the shoes that he was carrying, the cobbler quickly

replied that it was far indeed, for he had worn out all the shoes

in his pack trying to get there! Discouraged, the devil gave up

his plan and dropped his load of earth by the side of the

road.

Yet another theory, still prevalent in the 18th century, was

that the mound was the barrow of a great king named

"Zel" or "Sil." Zel was thought to have been

buried sitting upright upon his horse (which was perhaps meant to

explain why such a tall mound was needed). A variant upon this

theory was that the mound housed a life-size gold statue of a

horse and rider. This is the theory that Stukeley ascribes to.

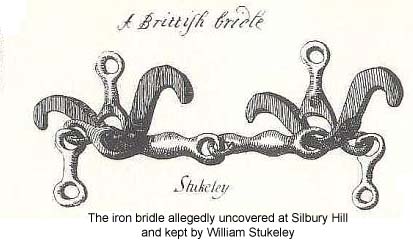

Stukeley claims that the remains of a horse and rider were indeed

discovered in 1723:

In the month of March, 1723, Mr. Halford order'd

some trees to be planted on this hill, in the middle of the noble

plain or area at top, which is 60 cubits diameter. The workmen

dug up the body of the great king there buried in the center,

very little below the surface. The bones extremely rotten, so

that they crumbled them in pieces with their fingers. The soil

was altogether chalk, dug from the side of the hill below, of

which the whole barrow is made. Six weeks after, I came luckily

to rescue a great curiosity which they took up there; an iron

chain, as they called it, which I bought of John Fowler, one of

the workmen; it was the bridle buried along with this monarch,

being only a solid body of rust . I immerg'd it in limner's

drying oil, and dry'd it carefully, keeping it ever since very

dry. it is now as fair and entire as when the workmen took it

up... There were deers horns, an iron knife with a bone handle

too, all excessively rotten, taken up along with it.

This, however, is the only record of any sort of burial

uncovered upon the mound, and judging not only by Stukeley's

description of its proximity to the surface, but also by his

drawing of the bridle itself, it must have been considerably

later than the construction of the hill.

Excavations into the interior of the mound have been conducted

in 1776, 1849, and 1967, but all have proven disappointing in

terms of uncovering artifacts or any indications of the purpose

of the mound. The only artifacts discovered within the mound

seem to relate to its construction (or perhaps to the

construction workers' lunches), and include various twigs, antler

tines, grains, flints, clay, ox bones and freshwater shells.

Unfortunately these shafts were not always filled in correctly,

leading to subsequent erosion and slippage of the mound itself.

In fact, more Roman artifacts have been found in and around the

mound than any other, including more than 100 coins in the ditch

that once surrounded the mound, and a platform cut into the mound

containing ashes from burnt artefacts. Many other Roman shafts

and wells have been found nearby, and Stukeley's illustrations

point out a "Roman camp" not far from Silbury. And

even as this article was being written, archaeologists discovered

evidence of a large-scale Roman settlement at the base of the

hill that no one had previously known about. This village

straddles the Roman main road where it crossed the River Kennet,

and was laid out with buildings and streets perpendicular to a

main north-south thoroughfare. The Roman Road itself breaks the

usual ruler-straight pattern of most such roads, to detour around

the hill. The village was discovered by non-invasive sensing

equipment during the process of restoring damage to the hill.

Today Silbury Hill stands on private land and is fenced in to

prevent climbers from causing further damage and erosion. It can

be viewed from the road or from a small carpark nearby. Sadly,

many people ignore the posted signs and fences and clamber up the

slope anyway; a rather scruffy-looking bunch of visitors was

doing just that when we viewed the mound, and then descended to

have a picnic at its base. So perhaps it is best to observe the

mound as its builders probably did: From a respectful distance.

West Kennet Long Barrow

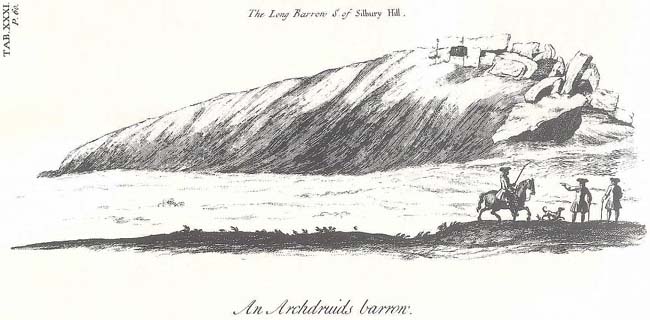

Close by Silbury Hill and yet another on the list of

"biggest" in Wiltshire is the West Kennet Long Barrow,

one of the largest chambered barrows in Britain. (Wiltshire, by

the way, holds the record not only for "biggest" but

"most," as it contains 148 of Britain's 260 long

barrows; to get an idea of their density, just stand on the grass

at Stonehenge and survey the skyline!) Close by Silbury Hill and yet another on the list of

"biggest" in Wiltshire is the West Kennet Long Barrow,

one of the largest chambered barrows in Britain. (Wiltshire, by

the way, holds the record not only for "biggest" but

"most," as it contains 148 of Britain's 260 long

barrows; to get an idea of their density, just stand on the grass

at Stonehenge and survey the skyline!)

West Kennet Long Barrow, which is managed by English Heritage,

stretches more than 320 feet from east to west and stands 8 feet

high. Only a small section of the barrow, however, was actually

used for burials. From the upright sarsen stones at the entrance

(which were repositioned in 1956), one enters the forecourt, and

thence into a passage grave that extends about 33 feet into the

barrow. This passage leads to five separate burial chambers: Two

on each side, and a larger polygonal chamber at the end.

Construction on the barrow began around 3600 BC, about 400 years

before the first building began at Stonehenge. It was thought to

have been used as a communal tomb for about 1000 years, though in

all, only about 46 burials have been found, ranging from infants

to old people. Unfortunately, many of the bones had been removed

from these burials, and no one seems quite sure whether this was

done at the time or by subsequent looters. A doctor in the 17th

century was known to have removed several bones for use in

compounding medicines (I'd rather not speculate as to what

kind of medicines!). Eventually the passage and chambers

were filled in with earth and stones, amid which have been found

bits of pottery, bone tools and beads.

As with Silbury Hill, very little is known about the purpose of

the barrow. According to one legend, a ghostly white figure

appears on the mound at dawn on Midsummer, accompanied by a white

hound with red ears. Since this type of hound was traditionally

associated with the underworld and the Wild Hunt (and with later

"fairy" mounds), this suggests that the mound itself

may have been considered an entrance to the underworld at one

time.

Unlike Silbury Hill, you can visit the barrow. You'll

find a small car park outside the village of West Kennet; from

there, you'll hike a steep half-mile to the ridge. Check the

English Heritage website for opening times and tour hours.

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Moira Allen has been writing and editing professionally for more than 30 years. She is the author of seven books and several hundred articles. She has been a lifelong Anglophile, and recently achieved her dream of living in England, spending nearly a year and a half in the history town of Hastings. Allen also hosts the Victorian history site VictorianVoices.net, a topical archive of thousands of articles from British and American Victorian periodicals. Allen currently resides in Maryland.

Article © 2007 Moira Allen.

Silbury Hill photos by Moira Allen; Long Barrow photo by Patrick Allen.

|