Avebury: Wiltshire's "Other" Stone Circle

by Moira Allen

When in Wiltshire, one should most certainly visit Stonehenge,

which is undoubtedly the world's most famous stone circle. But

one should also make time to visit Wiltshire's "other"

stone circle, Avebury -- which holds the distinction of being the

largest in the world.

Avebury is believed to have been constructed between

approximately 2600 and 2500 BC, though some estimates date the

Cove stones of the inner northern circle to as early as 3000 BC.

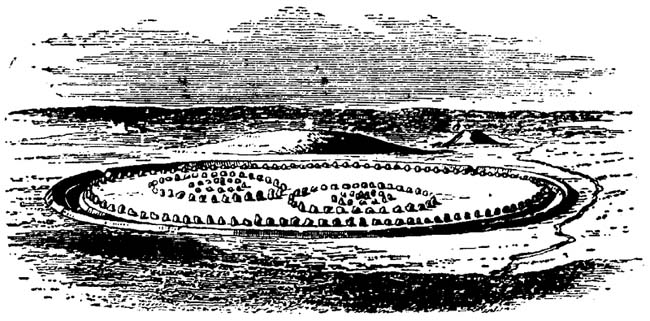

The site actually consists of several circles within circles. The

outermost ring is a massive earthwork: A grassy, 20-foot bank of

chalk a mile in circumference and 427 meters in diameter. Within

this bank lies a ditch, with four entrances (north, south, east,

and west). Within this ditch stands the first, and largest, ring

of stones, which encloses an area of nearly 28 acres. Once, this

ring consisted of 98 sarsen stones; today, only 27 remain

standing. It, in turn, encloses two smaller circles. The

northern inner ring measures 320 feet in diameter, with only four

of its original 27 stones still standing; the southern ring

measures 340 feet in diameter, and retains five of its original

29 stones.

The Cove Stones

By most accounts, these two inner rings are the oldest part of

the monument, and the oldest portion of all may be the huge Cove

stones, which once stood in the center of the northern circle.

Originally there were three; today only two remain, flanking the

modern path that winds to the top of the embankment. The sarsen

stones, like those of Stonehenge, were brought from Marlborough

Downs, some two miles away -- no small achievement, given that

some weighed as much as 40 tons! The stones were then raised

into position and often set as deeply as two feet into the chalk

soil. Excavations of the surrounding ditch show that its

creation involved digging away nearly 200,000 tons of rock, using

stone tools and antler picks. There are indications that this

ditch may have originally been filled with water, so that the

stones would have appeared to have been standing upon an island

or within a moat.

The village of Avebury itself, which now stands partly within and

amongst the stone circles, did not come into existence until

nearly 3000 years after the stones themselves were erected.

There is no mention of a village at this location in the Domesday

Book, though the church and earthwork are mentioned by the name

of Aureburie. The village is mentioned as Aveberia in 1180, and

Abury in 1386; the name "Avebury" first appears in

1689, but even today, many still pronounce the name

"A'bury." This was also the name used by antiquarian

William Stukeley, who wrote about the site in 1722 in his book

titled Abury - a Temple of the British Druids.

Dr. Stukeley spent 30 years visiting, recording, measuring,

drawing and chronicling the great stones of Avebury and the

surrounding landscape. He believed that the central rings

represented a serpent within a circle, whose head and tail were

represented by two avenues of sarsen stones extending more than a

mile into the countryside. In the process, he was a sad witness

to the continued destruction of the great circle.

Stukeley's Proposed Layout of the Avebury

"Temple"

This destruction began in the 14th century, when local

Christians sought to eradicate such monuments to pagan worship.

During that period, many stones were toppled and buried -- though

as the host of Avebury-Web notes, this may have actually

preserved them from the far worse fate that awaited those stones

that "survived" the religious zeal of the Middle Ages.

This fate was documented in graphic detail by Stukeley, who

recorded that of the supposed 188 stones of the original

"great temple," just over 40 were still visible in his

day -- 17 standing, 27 "thrown down or reclining."

(John Aubrey recorded 73 surviving stones in 1648; by 1815,

writer Richard Colt Hoare observed only 17.)

The destruction witnessed by Stukeley had nothing to do with

religion. In the 18th century, villagers sought to clear the

stones from their fields, or to break them up for use in

building. Stukeley writes:

Just before I visited this place... the inhabitants

were fallen into the custom of demolishing the stones, chiefly

out of covetousness of the little area of ground, each stood on.

First they dug great pits in the earth, and buried them. The

expence of digging the grave, was more than 30 years purchase of

the spot they possessed, when standing. After this, they found

out the kanck of burning them, which has made most miserable

havock of this famous temple. One Tom Robinson the

Herostratus of Abury,* is particularly eminent for

this kind of execution, and he very much glories in it. The

method is, to dig a pit by the side of the stone, till it falls

down, then to burn many loads of straw under it. They draw lines

of water along it when heated, and then with smart strokes of a

great sledge hammer, its prodigious bulk is divided into many

lesser parts. But this Atto de fe** commonly costs thirty

shillings in fire and labour, sometimes twice as much. They own

too 'tis excessive hard work, for these stones are often 18 foot

long, 13 broad, and 6 thick, that their weight crushes the stones

in pieces, which they lay under them to make them lie hollow for

burning, and for this purpose they raise them with timbers of 20

foot long, and more, by the help of twenty men, but often the

timbers were rent to pieces.

Stukeley goes on to write that a single stone could provide

enough pieces to build an ordinary house, but that because of the

nature of the stone, such a house "is always moist and dewy

in winter, which proves damp and unwholsome, and rots the

furniture. The custom of thus destroying them is so late, that I

could easily trace the obit of every stone; who did it,

for what purpose, and when, and by what method, what house or

wall was built out of it, and the like."

The salvation of the circle came in the person of Alexander

Keiller, who purchased the site in the 1930's. Keiller had the

site cleared of debris and surveyed, and began the process of

excavating and re-erecting the surviving stones, or marking with

concrete plinths the locations of stones that had vanished.

In one case, Keiller's work unearthed more than a stone!

When stone #9 of the southwest quadrant was raised, workers

discovered the skeleton of a man in the pit beneath. A leather

purse found with the body held a pair of scissors (thought to be

among the oldest ever found), a probe or lancet, a French coin,

and two 14th-century pennies from the reign of Edward I. The man

was believed to be either a tailor or a barber-surgeon; hence,

the stone has come to be known as the Barber stone. At first, it

was believed that when the stone was toppled in the 14th century,

it fell upon the man and crushed him, and he was simply left in

the grave thus created for him. More recent analysis of the

skeleton, however (which was believed lost in the Blitz but was

recently rediscovered in the Natural History Museum) suggests

that the man was already dead when placed in the pit beneath the

stone. Thus there is yet one more mystery associated with the

Avebury Circle! In one case, Keiller's work unearthed more than a stone!

When stone #9 of the southwest quadrant was raised, workers

discovered the skeleton of a man in the pit beneath. A leather

purse found with the body held a pair of scissors (thought to be

among the oldest ever found), a probe or lancet, a French coin,

and two 14th-century pennies from the reign of Edward I. The man

was believed to be either a tailor or a barber-surgeon; hence,

the stone has come to be known as the Barber stone. At first, it

was believed that when the stone was toppled in the 14th century,

it fell upon the man and crushed him, and he was simply left in

the grave thus created for him. More recent analysis of the

skeleton, however (which was believed lost in the Blitz but was

recently rediscovered in the Natural History Museum) suggests

that the man was already dead when placed in the pit beneath the

stone. Thus there is yet one more mystery associated with the

Avebury Circle! Unfortunately, Keiller's reconstruction

of the site came to a halt during World War II (when many

monuments that would be visible from the air were concealed or

camouflaged to prevent them being used as landmarks by German

planes). Since then, minor adjustments have been made to the

Cove stones, but otherwise the appearance of the henge has

remained unaltered.

More stones remain to be uncovered, however. In 1881, A.C. Smith

led a survey using probes to locate far more stones than Keiller

uncovered, and recent geophysical surveys by the National Trust

have confirmed the existence of at least 15 buried stones around

the eastern portion of the henge. This survey also revealed a

double ring of post holes in the northeast quadrant of the henge,

and another "circular feature" in the northwest

quadrant.

Thirty-six stones may not sound like a great many, but they are

enough to instantly strike the visitor with the sheer, awesome

grandeur of the site. What is also bound to strike any visitor

with a shred of imagination is the varied

"personalities" of the stones. Unlike some circles

where the stones are of similar sizes and shapes, the stones at

Avebury vary widely. Perhaps this is pure accident -- but when

one thinks of the effort that must have gone into hauling these

stones from their quarry two miles away, raising them upright,

and embedding them up to 24 inches in the earth, it's hard to

imagine that their appearance was utterly left to chance.

So perhaps the imaginative visitor can be forgiven for seeing in

one stone the figure of a shrouded woman, while another looks a

bit like a breaching whale. Yet another, partially split down

one side, gives the impression of a parent and child, while the

one my husband is examining rather seems to be examining him in

return!

After wandering amongst the Avebury stones, the visitor can view

some of the archaeological finds from the site at the Alexander

Keiller Museum, housed in a barn on the outskirts of the village.

Here, one will also find displays describing life in Neolithic

times, and a short film about the life and work of Keiller

himself. Be warned, however: The Barn is dimly lit and unheated,

and is sometimes shut down in very cold weather.

If you're looking for something a bit warmer but still on the

spooky side, consider taking lunch or tea in the only pub in the

world to be found in the middle of a stone circle: The Red Lion

Inn. The Red Lion serves good, solid pub grub, along with a side

helping of ghost stories. One of these centers around the old

well that sits right in the middle of one of the common rooms,

glassed over so that you can actually eat on it -- if you wish!

As the story goes, a soldier who lived at the inn came home from

the Civil War in the 17th century to discover that his wife had

taken a lover. Enraged, he shot his rival and slit his wife's

throat, and pitched her body into the well, tossing in a boulder

to seal it after her. Supposedly, the lady's ghost has haunted

the place ever since. Don't let this ruin your appetite, however

-- or spoil your rest, should you wish to take advantage of the

inn's bed-and-breakfast facilities!

Notes: *The term "auto da fe" (or auto

de fe) means "act of faith" and refers to the

Spanish Inquisition's ritual of judging and condemning heretics.

The ceremony has generally been thought to include executions by

burning at the stake (which is no doubt what Stukeley is alluding

to), though some sources claim that the actual executions were

held separately.

**Herostratus sought to make a name for himself by setting fire

to the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus (Turkey) in 356 BC. He

boasted proudly of his act, so the authorities not only executed

him but decreed that his name should never be spoken again, on

penalty of death. Obviously it didn't work, and the name

"Herostratus" subsquently became associated with the

idea of seeking glory through acts of destruction or violence.

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Moira Allen has been writing and editing professionally for more than 30 years. She is the author of seven books and several hundred articles. She has been a lifelong Anglophile, and recently achieved her dream of living in England, spending nearly a year and a half in the history town of Hastings. Allen also hosts the Victorian history site VictorianVoices.net, a topical archive of thousands of articles from British and American Victorian periodicals. Allen currently resides in Maryland.

Article and photos © 2007 Moira Allen

|