From Grindstones to Theorems: The History of Green's Mill

by Ian Douglas

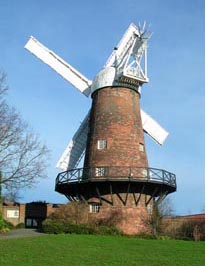

The white sails of Green's Windmill, spinning on a breezy day, are one of Nottingham's most romantic landmarks. Both a working mill and a museum to all kinds of mathematical magic, it looks proudly out over the terraced rooftops to the distant river Trent. Inside, huge grindstones are crushing wheat into flour once again, after an interruption of a century or so. Next door the new extension houses all kinds of scientific mysteries, from sparking plasma balls to magnetic pendulums. You might wonder what these have to do with a windmill and thereby hangs our tale.

The white sails of Green's Windmill, spinning on a breezy day, are one of Nottingham's most romantic landmarks. Both a working mill and a museum to all kinds of mathematical magic, it looks proudly out over the terraced rooftops to the distant river Trent. Inside, huge grindstones are crushing wheat into flour once again, after an interruption of a century or so. Next door the new extension houses all kinds of scientific mysteries, from sparking plasma balls to magnetic pendulums. You might wonder what these have to do with a windmill and thereby hangs our tale.

The year is 1831 and the country is gripped with riot fever in the wake of the reform bills. The Mill is facing one of its darkest hours. An ugly mob surrounds the Mill and means business. Things look bleak for the mill owner, George Green, trapped inside with his eldest daughter Jane.

Fearing for their lives, George sombrely orders young Jane to arm his musket. No doubt with a few prayers and curses, the miller fires over the heads of the crowd. The gamble pays off and the disgruntled people of Nottingham disperse and go home. And a good job too. Had poor George perished in the confrontation, the relentless march of progress would have received a serious setback. Without Green's mathematical genius, we might still be lighting the house with oil lamps and cooking the dinner in a coal-fired stove! Indeed, Einstein once remarked that George Green was twenty years ahead of his time.

But how did George come to be the miller? We need to go back further to 1800 to find out. Britain was at war with Napoleon, severely restricting the import of grain. This was compounded by failed harvests and famines at home. With rampant price hikes in the cost of bread, the poorer classes revolted and attacked, naturally enough, the bakeries. Contemporary accounts speak of mothers looting corn and crumbs for their starving children.

George's father was one of these unfortunate bakers. George himself was a mere seven years old and already slaving away at the family ovens. At a time when grain was as powerful as oil today, the stakes for Green Senior were high: Make a fortune, or face destruction at the hands of the unfed masses. Luckily for the Green dynasty, the old man had a hint of the same vision as his son.

Mr Green borrowed money from the mayor of Nottingham to buy a small leafy hilltop just outside the city. Today the area is a sea of slate and bricks, miner's housing thrown up by the Victorians. But in Mr. Green's day, only an old wooden post mill stood out against the trees, a relic of pre-industrial Britain. George's father had it dismantled and commissioned a spanking new brick mill. When finished in 1807 or thereabouts, this smock mill was the most modern in the East Midlands, a technological showpiece of its day. Its size, speed and strength enabled it to turn out sacks of grain at a rate that consigned the poor old post mills to the history books.

Mr Green borrowed money from the mayor of Nottingham to buy a small leafy hilltop just outside the city. Today the area is a sea of slate and bricks, miner's housing thrown up by the Victorians. But in Mr. Green's day, only an old wooden post mill stood out against the trees, a relic of pre-industrial Britain. George's father had it dismantled and commissioned a spanking new brick mill. When finished in 1807 or thereabouts, this smock mill was the most modern in the East Midlands, a technological showpiece of its day. Its size, speed and strength enabled it to turn out sacks of grain at a rate that consigned the poor old post mills to the history books.

Later, Green Senior moved his family -- including the 21 year-old budding prodigy, George -- into a house in the shadow of the mill. Perhaps it was those year of gazing up at the ever-turning sails of the mill that inspired George to greatness. After all, a windmill is a living science lab, a working demonstration of centrifuge, gravity, and velocity. Every component, from the mighty grindstones to the gears and cogs of the shaft, is constructed with an engineer's precision.

Young George Green made a small fortune from his windmilling business. He went on to study at Cambridge University and ended up as a fellow of one of its colleges. He penned several important mathematical papers concerning such topics as wave motion, the behaviour of light, and crystal structure. The most famous of his breakthroughs is Green's Function, named in his honour, which solves the puzzle of what physicists call 'differential linear equations'. Subsequent generations have taken these original theories and used them to explain electricity, magnetism and waves.

However, when George Green died in 1841, his reputation nearly died with him. The importance of his formulas was not yet realised and his work lay forgotten on the dusty shelves of his old Cambridge tutor. Luckily they were unearthed by noted scientist Lord Kelvin (1824-1907), who had heard of Green's essays while at Cambridge himself. Lord Kelvin introduced the work to the wider scientific community, who were astonished to discover that Green had the solutions to their problems. The miller from Nottingham, who died in obscurity, was on the road to international acclaim.

Sadly, Green's windmill fared less well. As Green's Function went from strength to strength, his mill fell into decline. With the rise of steam and then coal power, the old-fashioned windmill was no longer needed. The wooden sails rotted away, and eventually, in the early 1900's, the fantail came crashing through the roof of the miller's cottage and smashed a grand piano into smithereens.

Eventually the Mill changed hands and ended up a semi-ruined storehouse. In 1947 a fire incinerated what was left of the interior. Plans were made to demolish the charred ruins in the 1970's. Luckily for the Mill, Green's fame as a mathematician was ready to come home.

Nottingham University, aware of their famous forebear, suggested an alliance with the county council and local environmental groups. A daring plan to rebuild the Mill was hatched, and the rest, as they say, is history.

The renovated Mill opened in 1985, and quickly became a major tourist attraction. The Mill itself produces flour (when the wind's in right direction), while the adjacent museum keeps the memory of George Green alive. The exhibits demonstrate the invisible powers of electricity and magnetism in a hands-on style ideal for educating children. In an atmosphere sometimes reminiscent of a mad scientist's laboratory, there are plenty of levers to crank and switches to throw.

The renovated Mill opened in 1985, and quickly became a major tourist attraction. The Mill itself produces flour (when the wind's in right direction), while the adjacent museum keeps the memory of George Green alive. The exhibits demonstrate the invisible powers of electricity and magnetism in a hands-on style ideal for educating children. In an atmosphere sometimes reminiscent of a mad scientist's laboratory, there are plenty of levers to crank and switches to throw.

That's not quite the end of our story. 1993 saw the bicentennial of Green's birth. Among the many celebrations was a ceremony at Westminster Abbey. A plaque was unveiled in George's honour next to Sir Isaac Newton's grave. Finally, his enthusiasts say, George Green has found his rightful place.

George Green's life had its fair share of hardships and hard work, and he died an unknown. Yet his wind-powered mill lives on in our age of technological wonders as his memorial. It is a destiny he could not have foreseen and an inspiration to all who visit the mill.

How to get there: If approaching from the city centre the mill is signposted. Take Dale Road, which becomes Sneinton Dale. Take the left turning opposite St Stephen's Church (where George Green and his family are buried), onto Windmill lane. The first right is the car park for the Mill. Follow the footpath round the back of the Old School Hall, which emerges on top of Sneinton Hill, beside the windmill.

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Ian Douglas has recently returned to his hometown of Nottingham (UK) after many years living in the Far East. Based in Bangkok he eked out his meagre teacher's stipend by writing for the local press on a bizarre variety of topics, from golf to obscene rock formations, and anything else his editors were crazy enough to commission! In his spare time he paints and has held several solo exhibitions. The long years of exile fanned his love of all things historically British, and he is now rediscovering his heritage alongside his children.

Article and photos © 2005 Ian Douglas

|