Westminster Abbey: England's "Parish Church"

by Helen Gazeley

"The parish

church of the English-speaking peoples" seems an unlikely

description of Westminster Abbey, which is, after all, in a major

city, surrounded by government buildings. But it is packed with

the graves of world-famous people and has been the setting of

ceremonies watched internationally, from Queen Elizabeth's

coronation (1953) to the funeral of Diana, Princess of Wales

(1997), so perhaps one of the deans of the Abbey was right when

he said, "It belongs to all." "The parish

church of the English-speaking peoples" seems an unlikely

description of Westminster Abbey, which is, after all, in a major

city, surrounded by government buildings. But it is packed with

the graves of world-famous people and has been the setting of

ceremonies watched internationally, from Queen Elizabeth's

coronation (1953) to the funeral of Diana, Princess of Wales

(1997), so perhaps one of the deans of the Abbey was right when

he said, "It belongs to all."

A church has stood on this site since at least the seventh

century. In the eleventh century, Edward the Confessor (reigned

1042-1066) built another: "the first in England erected in the

fashion which all now follow at great expense", as William of

Malmesbury said of its Norman architecture. Edward actually

wanted to see Rome, but unrest was rife in England and he thought

that, if he went, he wouldn't have a throne to come back to. So

Edward swapped his pledge to visit the Pope with a promise to

build a great church to honour St Peter.

It's fitting, then, that the Abbey itself became a place of

pilgrimage, containing not only many relics (lost after the

Reformation but described by a medieval visitor as one of the

sights of London), but also the bones of Edward the Confessor

himself. When Henry III (1216-1272) began the erection of the

current abbey in 1245, he did so to venerate these bones, and

built the splendid shrine to Edward still there today.

To this shrine Henry V made solemn progress in 1415, to give

thanks for victory against the French at Agincourt. Despite the

loudly cheering citizens, triumphal arches, and fountains flowing

with wine, not once during the five-hour procession across London

did Henry smile. All glory should go to God and St George, he

said, and no thanks given to him.

The Court settled around the Abbey, and royal

dwellings grew into the Palace of Westminster (mostly destroyed

by fire, 1834), the heart of royal and government administration.

By the fifteenth century (while the current nave was still being

worked on) the Abbey precincts were a warren of tiny streets,

full of alehouses and shops, all vying for business from the

Abbey and royal household. The Court settled around the Abbey, and royal

dwellings grew into the Palace of Westminster (mostly destroyed

by fire, 1834), the heart of royal and government administration.

By the fifteenth century (while the current nave was still being

worked on) the Abbey precincts were a warren of tiny streets,

full of alehouses and shops, all vying for business from the

Abbey and royal household.

And, most importantly, the Abbey provided Sanctuary -- safety for

the oppressed, the hunted, the accused. Once within its

precincts, no one, not even the king, had the right

to drag you out. Established in the time of King Sebert (seventh

century), this privilege protected many during civil war, or

while they gathered evidence in their defence. It didn't protect

everyone, however.

In 1378, two squires escaped from the Tower of London. They fled

from the City, not just into the precincts, but into the Abbey

itself, where mass was being said. The Constable of the Tower

would not turn back and, with his followers, burst into the

service. An outraged sacristan barred their way, only to be cut

down, and one of the squires was murdered on the very steps of

the altar. The outcry shook the country.

Although the right of Sanctuary disappeared in the 17th century,

and is now marked only in nearby road-names, the idea persisted,

and the streets in the area continued to be considered safe haven

for many decades. These streets, which the Great Fire of London

(1666) never reached, were cleared in 1851, after Parliament

decreed that new houses should be built in a style suitable to

the dignity of the Abbey.

To gain an idea of what the area was like before the renovations,

rather than coming to the Abbey across the traffic-rimmed

Parliament Square, approach from the south. If you've spent a

morning at Tate Britain, it's a pleasant stroll downriver,

through Smith Square and into Great College Street. Enter Dean's

Yard and the Abbey gardens, where the Benedictine monks grew

their food, and take in the Jewel Tower, a tiny fragment of the

old Palace of Westminster.

Then brace

yourself for the Abbey itself. Not only crowded with visitors,

this "parish church" is crammed with memorials -- a "strange

muddle and miscellany" wrote Virginia Woolf, "of objects both

hallowed and ridiculous." Then brace

yourself for the Abbey itself. Not only crowded with visitors,

this "parish church" is crammed with memorials -- a "strange

muddle and miscellany" wrote Virginia Woolf, "of objects both

hallowed and ridiculous."

At one time, a famous Briton might confidently expect to finish

up here. On boarding the ship San Carlo, Nelson

proclaimed, "Victory! Or Westminster Abbey!" (Actually, he was

buried in St Paul's, but the two churches have always been

rivals). But think of a famous Briton, and he or she is quite

probably commemorated, if not actually buried, here. There are

too many to mention them all: writers -- Dickens, Browning,

Tennyson; musicians -- Handel, Purcell, Vaughan Williams;

politicians -- Pitt, Gladstone, Chamberlain; scientists,

architects, explorers and reformers.

Some might be surprised to be here. Charles Darwin, despite his

atheism, joined the Hall of Fame alongside his hero, Sir John

Herschel, and Sir Isaac Newton. In the words of The Times

newspaper on Darwin's final resting-place, perhaps "The Abbey

needed it more than it needed the Abbey."

The absence of others appears a glaring omission. In 1880, George

Eliot, one of England's finest novelists, was still deemed at her

death a scarlet woman (she had eloped in 1854). Her friends

feared that controversy would overshadow her achievements and

dropped their demands for her burial in Poets' Corner.

Scoundrels jostle with heroes. Look out for Tom

Thynne's memorial, on the wall near the organ. It shows the scene

of his murder in 1682. Thynne himself was so notorious a rake

that the Dean and Chapter refused to allow the normal eulogy on

his memorial and the space for it is still empty. Scoundrels jostle with heroes. Look out for Tom

Thynne's memorial, on the wall near the organ. It shows the scene

of his murder in 1682. Thynne himself was so notorious a rake

that the Dean and Chapter refused to allow the normal eulogy on

his memorial and the space for it is still empty.

And nearby, on the right-hand wall of the abbey, near the choir,

is Major André: hero or scoundrel, depending on your view

of the Atlantic. André was captured after collecting

intelligence supplied by Benedict Arnold. Sentenced to the

gallows, he asked to be shot, rather than hanged. The denial of

this request caused outrage in England and André's body

was brought back for a hero's burial.

On André's tomb is a likeness of George Washington. For

some time, whenever there was a row between Britain and America,

poor old Washington bore the brunt. His head was knocked off

twice almost as soon as the memorial was erected. The war of 1812

brought the need for another new head and the last

replacement was in the 1840s.

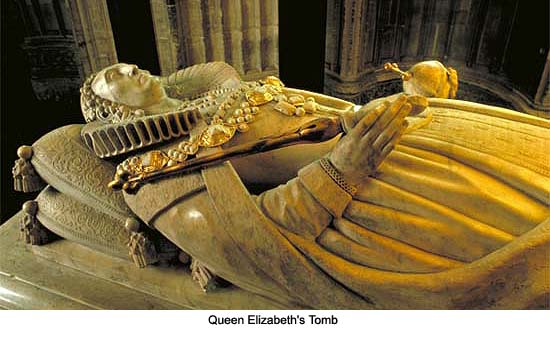

Above all, though, the Abbey is connected with royalty. More than

twenty monarchs are buried here, provoking the words from the

playwright, Francis Beaumont (1584-1616), who is also in Poets'

Corner, "Here's an acre sown indeed/With the richest, royalest

seed."

Queen Katherine of Valois, Henry V's bride, took longer to sow

than the rest. On her death in 1437, her coffin seems to have

remained in the Lady Chapel, open to view, until Henry VII

destroyed the Lady Chapel (in 1502) to make way for his own (it's

magnificent -- don't miss it). She was then moved next to her

husband, but still apparently open to the air. In 1669, Pepys

took his family to the Abbey. "Here we did see, by particular

favour, the body of Queen Katherine of ValoisÉAnd I did kiss her

mouth, reflecting upon it that I did kiss a Queen, and that this

was my birthday, 36 years old, that I did kiss a queen."

Katherine was finally interred in Henry V's chapel in 1878.

The royal tombs were matched in splendour by the funerals. Hugh

Walpole attended George II's. "The procession, through a line of

foot guards, every seventh man bearing a torch, the horse guards

lining the outside, their officers with drawn sabres and crape

sashes on horseback, the drums muffled, the fifes, bells tolling,

and minute guns -- all this was very solemn. But the charm was

the entrance of the Abbey, where we were received by the Dean and

Chapter in rich robes, the choir and alms-men bearing torches;

the whole Abbey so illuminated, that one saw it to greater

advantage than by day."

Henry V's coffin arrived after a two-month funeral

procession from France. On the carriage which bore it was a

greater than life-size image of the king, dressed in royal robes,

sceptre in one hand, a golden apple in the other. Surrounded by

torch-bearers and clergy dressed in white, the royal household

dressed in black, it must have been quite a sight when these and

three of Henry's favourite battle-horses advanced to the altar. Henry V's coffin arrived after a two-month funeral

procession from France. On the carriage which bore it was a

greater than life-size image of the king, dressed in royal robes,

sceptre in one hand, a golden apple in the other. Surrounded by

torch-bearers and clergy dressed in white, the royal household

dressed in black, it must have been quite a sight when these and

three of Henry's favourite battle-horses advanced to the altar.

Supremely, though, Westminster Abbey is a place of coronations.

Since William I in 1066, English monarchs have been crowned here.

The present Abbey was built to serve as a coronation church,

which is why there is a larger than normal space between the

Choir and the steps leading up to the High Altar. Most of the

ceremony occurs here, and you might like to linger and imagine

the scenes.

The diarist Celia Fiennes was present when Queen Anne (1702-1714)

was crowned. Dressed in crimson velvet with a six-yard long

train, the queen wore an under-robe "of gold tissue, very rich

embroidery of jewelsÉher petticoat the sameÉwith gold and silver

lace, between rows of diamonds." In her hair were diamonds which

"brilled and flamed." The altar "was finely decked with gold

tissue carpet and fine linen, on the top all the plate of the

Abbey set", while the officials were arrayed "in very rich copes

and mitres, black velvet embroidered with gold stars, or else

tissue of gold and silver."

Possibly no coronation can compare with George IV's, though. This

rather vain man demanded sumptuous proceedings with no thought

for expense. £24,000 was spent on the coronation robes

alone, when his successor, William IV (1830-37) spent only

£50,000 on the entire day. George wore a crimson train,

ornamented with golden stars, twenty-seven feet long. "Something

rustles, and a being buried in satin, feathers, and diamonds

rolls gracefully into his seat," said painter Benjamin Robert

Haydon (1786-1846).

George had his comeuppance as he was almost overcome

with the heat of his robes. One royal page reported that the king

had required no fewer than nineteen handkerchiefs to mop his

royal brow while the peers paid him Homage. And "when the

Archbishop preached about burthens of Royalty, the King was seen

to wink at the Duke of York and point to his immense train." George had his comeuppance as he was almost overcome

with the heat of his robes. One royal page reported that the king

had required no fewer than nineteen handkerchiefs to mop his

royal brow while the peers paid him Homage. And "when the

Archbishop preached about burthens of Royalty, the King was seen

to wink at the Duke of York and point to his immense train."

Like George IV, congregations of the 18th and 19th centuries

showed little respect for the service. When the priest began his

sermon at George III's coronation, most of the congregation took

the opportunity "to eat their meal, when the general clattering

of knives, forks, plates, and glasses that ensued, produced a

most ridiculous effect, and a universal burst of laughter

followed."

But in other eras the ceremony engendered more respect and had,

perhaps, greater impact on those involved. In medieval times,

royalists believed that the anointing during the ceremony raised

the king to new heights: he became blessed of God. And while the

Reformation did away with any lingering idea that crowning was a

sacrament, coronation still had its effect. Queen Mary, the wife

of George V (1910-1936) "was almost shrinking as she walked up

the aisle," said the first Viscount Murray. "The contrast on her

'return' -- crowned -- was magnetic, as if she had undergone some

marvellous transformation. Instead of the shy creature for whom

one had felt pity, one saw her emerge from the ceremony with a

bearing and dignity, and a quiet confidence, signifying that she

really felt that she was Queen of this great Empire, and that she

derived strength and legitimate pride from the knowledge of

it."

And this, perhaps, is the secret of the Abbey. In the

ever-changing heart of London, it represents a continuity of

British history more than any other building. Standing on the

foundations of the old Norman abbey, it cradles and commemorates

heroes who have contributed to the world as well as Britain, and

returns every so often to the forefront of history as another

monarch is crowned before the altar.

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Helen Gazeley is a freelance writer whose articles have appeared in the Daily Telegraph, Artists and Illustrators, Organic and Healthy Living and Kitchen Garden Magazine. She also writes a regular column for Organic Gardening. London and eating are two major enjoyments, so she knows a decent place to eat near any major attraction.

Article © 2006 Helen Gazeley.

Photos courtesy of Britainonview.com; André Memorial photo courtesy of Westminster Abbey.

|