A Walking Tour of London's Jewish Past

by Joseph Hayes

A tour of London's Jewish past is full of

qualifiers, language with many references to former buildings,

places that "used to be" and use of the word

"original" -- sites of interest, with explanation. A tour of London's Jewish past is full of

qualifiers, language with many references to former buildings,

places that "used to be" and use of the word

"original" -- sites of interest, with explanation.

The area known as the East End is many hamlets adjoining the old

City of London, the Cockney section famously within hearing

distance of the bells of St. Mary-le-Bow church. From the Thames

River on the south border to Bethnal Green Road on the north and

Aldgate High Street, it is a place now known for theater and

tours of the notorious Tower, the home of Sherlock Holmes, the

Elephant Man and Jack the Ripper. Always a magnet for immigrants

searching for a better life in cosmopolitan London, it was also,

at the beginning of the 20th Century, home to an estimated

300,000 Jews, a Quarter with residents from Eastern Europe, Spain

and Portugal. With more than 150 synagogues before the start of

World War II, now there are only four, all of them at risk, and

an elderly Jewish population of less than 3,000.

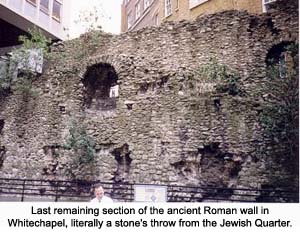

Like the shifting fate of the Jewish people themselves, the cycle

of new immigration is never ending and life in the East End

continually changes. Part of the ancient Roman wall that once

surrounded Londinium is still standing, literally a stone's throw

from the oldest remaining Jewish house of worship. More of the

wall remains than signs of Jewish life, which in its turn

supplanted older, established communities. What is now called the

Brick Lane Mosque, the Bengali Jamme Masjid, was the Spitalfields

Great Synagogue in the 19th century -- but before that it was a

Methodist chapel, and before that a church for Hugenots escaping

persecution in France. Punjabis, Somalis and expats from Pakistan

and Bangladesh currently fill apartments and own shops that once

held Kosher butchers and bookstores of rabbinical study. But the

Jewish history of London has left its mark, as can be seen by

walking the Quarter with an educated eye.

The first published mention of a Jewish quarter in

London was in 1128, although their presence has been felt at

least from the time of the Norman Conquest in 1066. Jewry Street

in London's financial center was where Jews settled both before

their expulsion in 1290 and after the resettlement, 350 years

later. From the late 1800s to just before WWII, thousands of Jews

from Poland, Romania and Russia arrived in England, many crowding

into the two square miles of Whitechapel and Stepney, close to

where their ships had docked. My own grandfather, fleeing the

dual anti-Semitism of the Reich and Tsarist pogroms, passed

through London on his way from Russia to America. The first published mention of a Jewish quarter in

London was in 1128, although their presence has been felt at

least from the time of the Norman Conquest in 1066. Jewry Street

in London's financial center was where Jews settled both before

their expulsion in 1290 and after the resettlement, 350 years

later. From the late 1800s to just before WWII, thousands of Jews

from Poland, Romania and Russia arrived in England, many crowding

into the two square miles of Whitechapel and Stepney, close to

where their ships had docked. My own grandfather, fleeing the

dual anti-Semitism of the Reich and Tsarist pogroms, passed

through London on his way from Russia to America.

He would have heard merchants in the old markets and bnarrow

streets of Petticoat Lane and Brick Lane, pushing wooden carts

and shouting prices in Yiddish. Cabinet makers, tailors,

shoesmiths and cigarette makers literally rubbed shoulders with a

thriving community of actors continuing the great tradition of

Yiddish theater. Yards of dyed fabric stretched across the

"tenter grounds" of Spitalsfield Fields, home of dozens

of cloth makers, a section of town that became for a brief time

part of the "playground" of Jack the Ripper -- several

witnesses to the heinous crimes (as well as a few suspects) were

local Jews.

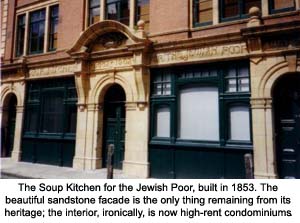

The phantom remnants of the East End's Jewish

past are all around. Rectory Square holds a Victorian apartment

building now called Temple Court, once the East London Synagogue,

and still contains Moorish tile interiors, stained glass and

commemorative plaques. The beautiful sandstone facade is the only

thing remaining from the heritage of the Soup Kitchen for the

Jewish Poor in Brune Street, opened in 1902 to feed indigent

local residents. The interior, ironically, is now high-rent

condominiums. The Whitechapel offices of the Jewish Daily News,

closed for decades, still carries a Star of David sign that

currently hangs above a men's clothing store. A similar Star is

carved into the façade of a building on Bethnal Green Rd,

an artist's studio that was once Bethnal Green Great Synagogue.

Walking on to Brick Lane, the only remnants of a thriving Jewish

social scene are two bagel shops, where Kosher meals are still

available for the discerning. Princelet Street Synagogue became a

museum, now derelict and closed, and the New Road Synagogue is a

clothing factory. The phantom remnants of the East End's Jewish

past are all around. Rectory Square holds a Victorian apartment

building now called Temple Court, once the East London Synagogue,

and still contains Moorish tile interiors, stained glass and

commemorative plaques. The beautiful sandstone facade is the only

thing remaining from the heritage of the Soup Kitchen for the

Jewish Poor in Brune Street, opened in 1902 to feed indigent

local residents. The interior, ironically, is now high-rent

condominiums. The Whitechapel offices of the Jewish Daily News,

closed for decades, still carries a Star of David sign that

currently hangs above a men's clothing store. A similar Star is

carved into the façade of a building on Bethnal Green Rd,

an artist's studio that was once Bethnal Green Great Synagogue.

Walking on to Brick Lane, the only remnants of a thriving Jewish

social scene are two bagel shops, where Kosher meals are still

available for the discerning. Princelet Street Synagogue became a

museum, now derelict and closed, and the New Road Synagogue is a

clothing factory.

War has always had an effect on the East End. It was from this

area that many of the volunteers for what became known as The

Jewish Legion were recruited, sent in 1917 to liberate Palestine

from Turkish rule. There has been a great deal of reconstruction,

as the area, so close to strategic docks, became a prime target

for German bombing during the Second World War. The Philpot St.

Great Synagogue and its attached shul (Hebrew school) were

obliterated by German warplanes.

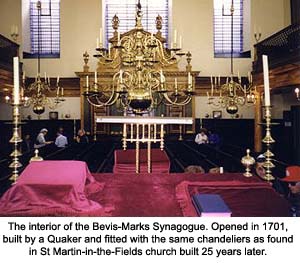

But some houses of worship remain. Fieldgate Street

Great Synagogue, founded in 1899, is a tiny building dwarfed by

the giant East London Mosque now beside it. Nearby is Rowton

House, a lodging house where Lenin, Stalin and Trotsky lived

while in exile. Much larger and grander is Bevis Marks,

constructed for the Sephardic (Spanish/Portuguese) Jewish

community in 1658 by a Quaker who refused to take payment for

building a "holy place", and fitted with the same

chandeliers as found in the church of St. Martin-in-the-Fields

built 25 years later. The synagogue, originally called Shar

HaShamayim ("Gate of Heaven") is the UK's oldest,

modeled after the Portuguese Synagogue in Amsterdam and built

inside a courtyard, hidden from view at a time when synagogues

were not permitted on public streets. But some houses of worship remain. Fieldgate Street

Great Synagogue, founded in 1899, is a tiny building dwarfed by

the giant East London Mosque now beside it. Nearby is Rowton

House, a lodging house where Lenin, Stalin and Trotsky lived

while in exile. Much larger and grander is Bevis Marks,

constructed for the Sephardic (Spanish/Portuguese) Jewish

community in 1658 by a Quaker who refused to take payment for

building a "holy place", and fitted with the same

chandeliers as found in the church of St. Martin-in-the-Fields

built 25 years later. The synagogue, originally called Shar

HaShamayim ("Gate of Heaven") is the UK's oldest,

modeled after the Portuguese Synagogue in Amsterdam and built

inside a courtyard, hidden from view at a time when synagogues

were not permitted on public streets.

Sandy's Row Synagogue, founded by Dutch immigrants in

Spitalfields in 1854, is in the opposite direction from Fieldgate

Street, as is the Nelson Street Synagogue, the last to be built

in the East End in 1923. And much like Brick Lane, the Mile End

and Bow Synagogue is now a Gurdwara, a Sikh place of worship, its

marble front step covered with the shoes of the devotees

inside.

As the Jewish community thrived and life shifted west and north

to London's suburbs, the changing population brought a change in

local shops. Hessel Street Market, Frumkins wine merchants, even

legendary delicatessen Blooms Kosher (reputed to have England's

rudest waiters) eventually closed. Long gone, Feldman's Post

Office on Whitechapel Road was the homing beacon for many new

immigrant Jews to London, a place to find lodging, relatives,

even a loan. The voices on Petticoat Lane now have an Eastern

rhythm as the Market, once the mainstay of the Jewish community,

provides familiar staples for the East End's current residents.

Landmarks of the Jewish past are worth seeking out. The St.

Swithen's Lane house of Benjamin Disraeli, Queen Victoria's Prime

Minister, still stands, as does the headquarters of the

Rothschild corporation, whose founder, Nathan Meyer Rothschild,

is buried in the Brady Street Cemetery, a Reformed Jewish burial

ground closed since 1858.

If my grandfather could walk the Jewish Quarter now, there would

be little there for him to recognize, aside from the feeling of

new immigrants seeking a better life on its still-cobbled

streets.

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Freelance journalist Joseph Hayes writes for print and online publications worldwide. His plays have been performed in New York, California, Florida, Oregon and England. Hayes' most recent publications include the Eyewitness Travel Guide: Walt Disney World Resort & Orlando for Dorling Kindersley, and pieces in Style1900 and the Orlando Sentinel. He is cofounder of The Burry Man Writers Center (http://www.burryman.com), a worldwide community of writers, and also hosts a personal site at http://www.jrhayes.net.

Article and photos © 2006 Joseph Hayes

|