The Globe Theatre: London's Woodon "O"

by Elise Warner

A crowd of twentieth century "groundlings" stands in

the open yard of the new Globe Theatre in Bankside, London.

Admission is £5.00; in the early 1600's, at the first Globe

Theatre, Shakespeare's "Wooden O," groundlings (commoners) paid

one English penny. Two pennies entitled a patron to a seat on a

bench in the gallery protected from sun and rain by a thatched

roof made of water reed. Three pennies bought a cushioned seat

close to the stage where one could see and be seen. The most

prestigious seats of all, the Lord's rooms -- at six pennies --

were behind and above the stage.

The groundlings, also known as "stinkards" (as they rarely

washed themselves or their clothes) stood in a yard covered with

a mixture of hazelnut shells, cinders, ash, sand and silt. Here

they ate and drank, fought, cheered, hissed and sometimes

critiqued an offending actor by throwing an orange. The orange

was a useful fruit; its scent protected the nose from stench and

it could be eaten when a groundling felt a pang of hunger.

Today, most of us shower, deodorize, sip from bottles of spring

water and enjoy an ice cream, but cheers for the British and

hisses for the French are still heard if you catch a performance

of Shakespeare's Henry the Fifth.

Born April 23, 1564, on Henley Street in Stratford-upon-Avon,

a two-day ride from the deathly plague that was sweeping through

London, William Shakespeare was the oldest son and first

surviving child of Mary Arden and John Shakespeare. Two sisters

had been born before him; one died at birth, the other at four

months of age. The town's bell would ring by July, mourning the

children struck down by the deadly epidemic, but Shakespeare

survived.

His father worked as a yeoman farmer, a craftsman, a glover, a

merchant, a constable and one of the borough's two chamberlains

in charge of property and finances. His mother was the youngest

and most favored of eight daughters of a farmer, who named her

executor of his will and left her his most valuable property.

Most scholars believe that both parents could read and do sums.

Educated at the local grammar school, young Will Shakespeare

would be transported by the traveling players who performed

"pastymes," or plays in Stratford-on-Avon. The townspeople were

entertained by dramas and spectacles presented in markets, the

Bridge Street innyards and the Gild Hall. The first plays

Elizabethan audiences attended were performed in inns and

courtyards. There was no gas lighting, limelight, electricity,

incandescent lamps or computer controlled light-boards.

Performances took place outdoors during daylight hours, allowing

eye contact between the actor and the observer. The players

presented medieval and religious plays as well as new works.

Stratford also had amateur mummers and a Lord of Misrule, the

master of revels, from Christmas to 12th Night. During John

Shakespeare's tenure as bailiff, two companies, The Queen's men

and the Earl of Worcester's men, played Stratford's Guild

Hall.

Accounts of Shakespeare's life between 1583 and 1588, the year

he arrived in London, are rather hazy. As John Shakespeare's

oldest son, William should have been apprenticed to his father's

business, but John's fortunes were in decline during this period

and Will, according to some, was apprenticed to a butcher. Then

there is the oft-repeated scuttlebutt that claims Shakespeare

left Stratford under a cloud after he was caught poaching in the

deer park of Sir Thomas Lucy, a local Justice of the Peace. Lucy

is portrayed as Justice Shallow in The Merry Wives of

Windsor. Other chronicles have Shakespeare spending some

time as a schoolmaster. The strongest possibility is a that

traveling theatre company passed through Stratford and invited

Shakespeare to join the troupe. As a dramatist or "scriviner"

and minor actor, he would be of great use to the players.

Shakespeare's

London was a city of contrasts. London Bridge, the Tower of

London, tall buildings, royal palaces and rows of shops competed

with streets littered with the rotting corpses of animals and

body wastes tossed indiscriminately into alleys. The sights, the

sounds, the energy of the city must have nourished his talents;

he began working as an actor and playwright with several

companies including The Queens Men, Pembroke's Men and Lord

Strange's Men. The troupes often disbanded and regrouped.

Shakespeare joined James Burbage and his sons, Richard and

Cuthbert, offering his talents as a dramatist and actor.

To avoid the restrictions imposed by authorities, theatres

were built outside the walls of London. In 1576, James Burbage,

an actor/manager, built a playhouse at Shoreditch, a leased site

in Finesbury Fields. He called it The Theatre. Over the next 60

years, 17 other playhouses were built around the city. At

Southwark, across the River Thames and easily reached by boat or

bridge, the theatres were close to bull- and bear-baiting rings,

prisons, cockpits and brothels. When flags were raised and

trumpets blasted the air announcing a performance, workers were

lured away from jobs -- which was just of the many reasons

London's Lord Mayors disapproved of plays. Plays encouraged

lust, sacrilege and sloth.

The Lord Mayors tried and failed to get the plays banned, but

the companies were protected by the Royal's Privy Council and

appeared by Royal Command. Shakespeare was a charter member of a

new theatre company under the patronage of Lord Hunsdon,

Chamberlain to Queen Elizabeth and an officer of the Privy

Council, in charge of Her Majesty's entertainment. Known as the

Lord Chamberlain's Men, they performed at The Theatre. Needing

money, the Burbages, who owned half the lease, offered shares in

The Theatre to five leading actors. Shakespeare accepted and

received a share of one eighth.

Perhaps his success led to a critique published in 1592 by

actor and dramatist Robert Greene, in Greene's "Groatsworth of

Wit," one of the earliest known references to Shakespeare.

Greene, one of a group of dramatists known as wits, who had

earned degrees at Oxford and Cambridge, attacked the Bard as "An

Upstart Crow." Greene was soon proved wrong; half of

Shakespeare's plays were published during the playwright's own

lifetime and by the time Shakespeare entered his early thirties,

he was established as a man of property.

In 1593 plague once again closed London's theatres, and over

10,000 deaths were reported. By 1594, the Lord Mayor succeeded in

reaching an agreement with the Lord Chamberlain. All companies,

except for the Lord Chamberlain's (who performed at The

Theatre), and The Lord Admiral's (who performed at the Rose),

were banned. Christopher Marlowe's plays were performed at the

Rose, Shakespeare's at The Theatre.

In 1597, the Burbage's landlord, Giles Allen, a Puritan who

disapproved of theatre, refused to renew the lease at the

Finesbury site. The company tried to build a theatre in a hall

at the Blackfriar's near St. Paul's Cathedral, but were stopped

by a petition circulated by residents of that upscale district.

The petition sited... "A general inconvenience to all the

inhabitants... All manner of vagrant and lewde persons that... will

come thither and worke all manner of mischeefs." His plan for an

indoor theatre thwarted, James Burbage died three months later,

leaving his two sons to carry on. The company rented a

playhouse, the Curtain, for two years, but 1597 and 1598 brought

a reversal in their fortunes and the company was forced to sell

the playbooks of Richard III, Richard II, Henry IV and

Love's Labor Lost.

In 1598, the Burbages took a 31-year lease on a plot of land

on Bankside. Then, late at night, during a heavy snowfall, the

Burbages transported timber and whatever else could be salvaged

from The Theatre across London Bridge to Southwark, and the first

Globe theatre was built. Henry the Fifth and As You

Like It were performed that year, and on September 21 a Swiss

visitor, Thomas Platter, "in the house with the thatched roof

witnessed an excellent performance of the first Emperor Julius

Caesar."

In Shakespeare's day, plays were written for

particular companies, becoming their exclusive property. The

playwrights -- then known as poets -- received a flat fee and

possibly a portion of the second day's receipts unless, like

Shakespeare, the poet owned a share. Shakespeare probably agreed

to write two plays a year for the company. Richard Burbage, the

leading tragedian, gained from his working friendship with

Shakespeare, originating the title roles in Hamlet, Lear,

Othello and Macbeth and becoming the foremost actor of

his time. Their arrangement was unusual and highly successful;

the Globe became "the glory of the Banke."

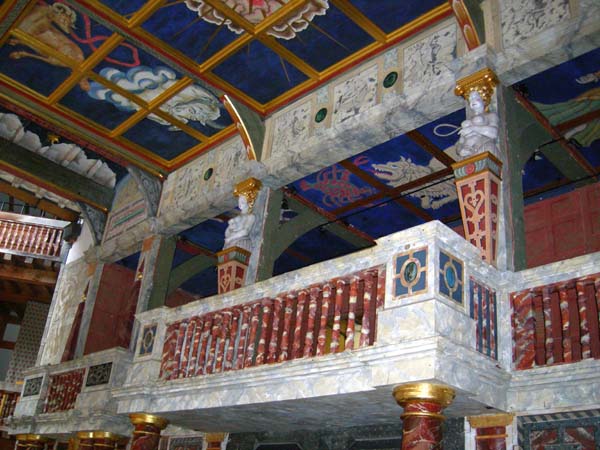

The Globe had a central "discovery place." Double

doors, covered with finely embroidered hangings, a curtain or

both enabled the actor to reach the upper level for balcony

scenes. Above that was a room with machinery for special

effects; cannon were fired, angels or ghosts descended and a trap

door in the floor led to hell. Wooden stage posts, painted to

look like marble, supported a canopy that represented heaven,

filled with clouds, stars, moons and the sun. The canopy did

double duty, protecting the actors and their costumes from the

sun.

Elizabeth I enjoyed masques -- a dramatic entertainment based

on mythological or allegorical themes -- and plays at Christmas.

She appointed A Master of Revels, who acted as a

producer/director and guardian of morals, in addition to

providing extra costumes and a hall to be used for the

performance. When Elizabeth died in 1603, James VI of Scotland

became James I of England and succeeded her. James loved the

arts, particularly theatre and the Chamberlain's Men. He

demanded they come under his patronage and granted a royal

patent. Their name changed to the King's Men. Shakespeare's

company played the Globe in winter and summer until 1608, when

the company began to play winters indoors at the Blackfriar's

theatre. When plague caused the closing of theatres, James

provided the troupe with engagements, playing for royalty outside

London until the danger had passed.

Today, as the doors open at the Globe, the audience is

transported back to the 16th century. Spectators, engrossed in

conversation, are barely aware of the faint throb of a drum;

music from the Elizabethan period underscores the play just as it

did in Shakespeare's day. The beat becomes deliberate as the

Musicians of the Globe appear, playing trumpet, cornet, sackbut

and percussion. The sound becomes intense as the Players fill

the stage. A stave pounds the floor. Excitement reaches a

crescendo as every onlooker melds with this "band of brothers"

appearing within the Globe, described by Shakespeare in Henry

the Fifth as the "Wooden O."

Fire destroyed the Globe during a performance of Henry

VIII. A piece of wadding fired from one of the stage cannons

landed on the thatched roof, smoldered, smoked -- ignored by a

group of spectators totally involved in the performance --and

finally burst into flame. The Globe burned to the ground in less

than an hour, but the audience of three thousand managed to

escape through the two exits. One patron's pants caught fire but

a quick-thinking friend extinguished the flames with a bottle of

ale. The second Globe, built on the foundations of the first,

was rebuilt immediately; this time it sported a tiled roof and

was thought to be "the fairest that ever was in England."

Shakespeare retired to Stratford-upon-Avon in 1613 and died in

1616; he bequeathed a ring to Richard Burbage as a token of

friendship. The Globe prospered until the Civil War of 1642,

when the Puritans closed all theatres. By 1644, the theatre had

been torn down, its foundations entombed by tenements.

Sam Wanamaker, a young American stage and motion picture actor

and director, searched for the site of the old Globe when he

arrived in London in 1949. All he found was a blackened bronze

plaque on the wall of a brewery. He founded the Shakespeare

Globe Trust and the rest of his life was dedicated to rebuilding

Shakespeare's Globe as a living memorial to the greatest

playwright of all time. His dream was realized: today's

enthusiastic audience enjoys the same excitement and pleasure

that Elizabethan patrons participated in so many centuries ago.

The Globe is the centerpiece of the Shakespearean Globe

Centre. It now has two more exits; fireboards are between the

walls and under the thatched roof. A close look at the thatch,

treated with a chemical fire retardant, will disclose nozzles of

a sprinkler system. Composed of water reed and lime, the

thatched roof of the Globe is the first to be seen in London

since 1666.

In addition to the theatre, the Centre also houses an autumn

education programme with staged readings, a lecture series and an

exhibition on the London where Shakespeare lived and worked.

William Shakespeare is the most widely read author in English

speaking countries; his work is revered all over the world. Ben

Jonson proved prophetic when he wrote of his friend, "Thou art a

monument, without a tomb, and art alive still, while thy book

doth live."

Related Articles:

- Visiting Shakespeare's Stratford-upon-Avon, by Pearl Harris

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/towns/stratford.shtml

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Elise Warner's articles have been published in The Travel Section of The Washington Post and in magazines such as Rock & Gem, Historic Traveler, Animal Watch, Kaleidoscope, 50 and Forward and Pennsylvania and on-line at literarytraveler.com and internationalliving.com.

Article © 2006 Elise Warner

Photos © 2008 Moira Allen

|