Hardwick Hall, "More Glass Than Wall"

by Julia Hickey

Ascend the hill towards the dramatic silhouette

on the Derbyshire skyline. Here, looking towards the patchwork

hills of the Peak District, is Hardwick Hall, an icon of Tudor

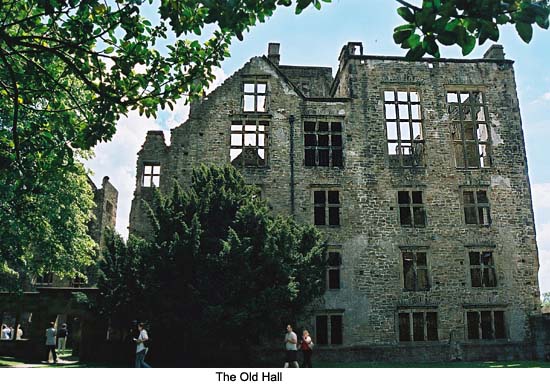

architecture. The ruins of the nearby Old Hall are an imposing

reminder of earlier times. Both buildings are part of the legacy

left by a singleminded Derbyshire lass: Elizabeth, Countess of

Shrewsbury, who began life as plain Bess of Hardwick. Ascend the hill towards the dramatic silhouette

on the Derbyshire skyline. Here, looking towards the patchwork

hills of the Peak District, is Hardwick Hall, an icon of Tudor

architecture. The ruins of the nearby Old Hall are an imposing

reminder of earlier times. Both buildings are part of the legacy

left by a singleminded Derbyshire lass: Elizabeth, Countess of

Shrewsbury, who began life as plain Bess of Hardwick.

Her mark is upon everything, from the grand ES turrets that

proclaim her ownership of the glittering symmetrical sandstone

Hall to the curling Cavendish snakes that twist around the lead

drainpipes. The house is her creation and her monument. It took

just seven years to build following the death of her estranged

husband and one-time gaoler to Mary Queen of Scots -- the Earl of

Shrewsbury -- in 1590.

Pass through the portals of the porter's lodge into a walled

garden. Its symmetry mirrors the house and it doesn't seem to

matter what the season is, for the gardeners always provide a

riot of color and texture. Walk up the path to the wide porch

with its tapering columns. It is often possible to encounter a

Tudor housekeeper here. In the summer months she relates tales of

Bess of Hardwick, who seemed driven to create the most

magnificent house in the kingdom. Little wonder she was also

called "the costly countess."

Proceed into the baronial hall dominated by Bess's coat of arms

supported by two stags, cross the creamy flags and take in the

assorted weaponry, mounted stags heads, enormous hearth and long

oak table with matching benches. This room is not only the main

entrance, but harks back to a time when servants were part of the

household dining in the hall, sleeping in the same rooms or near

their masters and mistresses rather than being kept below stairs. All of it is presided over by a portrait of Bess.

Study the delightful patchwork screens before continuing out of

the hall. The images are created from a rich patchwork of

velvets, silks and cloth of gold. Much of the material comes

from medieval ecclesiastical vestments. The colour and the

detail can only be maintained by carefully controlled lighting.

It is for this reason that Hardwick, despite the number of

windows it boasts, seems dimly lit. The needlework collection

here is of national importance -- indeed, the screens are perhaps

the most important part of the collection as they represent a

complete set of Tudor hangings. All kinds of needlework

techniques and fabrics are on display throughout the house --

many examples worked by Bess herself, others by her embroiderer

called Webb. Visitors must also wonder how Beth must have been

influenced by the other great Tudor needlewoman, Mary Queen of

Scots.

Take

advantage of the Threads of Time exhibition housed in the

ground floor nursery to see some of the needlework in more

detail, learn about the techniques that created the golden

caterpillars and butterflies that decorate much of the furniture

and find out how important the symbolism contained in the

tapestries was to Beth and her contemporaries. It is perhaps of

no surprise that much of Bess's needlework portrays family crests

and it is not hard to imagine hawk-eyed Bess selecting tapestries

from Brussels that she believed told her own story and celebrated

her own characteristics. Take

advantage of the Threads of Time exhibition housed in the

ground floor nursery to see some of the needlework in more

detail, learn about the techniques that created the golden

caterpillars and butterflies that decorate much of the furniture

and find out how important the symbolism contained in the

tapestries was to Beth and her contemporaries. It is perhaps of

no surprise that much of Bess's needlework portrays family crests

and it is not hard to imagine hawk-eyed Bess selecting tapestries

from Brussels that she believed told her own story and celebrated

her own characteristics.

Continue through the Evidence Room, where countless wooden boxes

are filled with documents detailing every aspect of Bess's

kingdom, and into a room dominated by a partially completed

hanging. Take advantage of a book or audio commentary to

discover the fascinating process from selecting and creating a

design to the countless hours of painstaking stitchery required

for a finished piece.

Walk through twisting hallways partitioned by sturdy doors fitted

with stout bolts and heavy locks to the broad stair case that

sweeps majestically up to the first floor landing and Bess's

private chapel. The arras in the chapel is as bright as the day

it was made. It is also possible from the careful seating

arrangements to see the significance that the Countess and her

descendants placed on social hierarchy. Pause on the continuing

upwards climb to admire the great glass lantern with its panes of

bull's eye glass -- it is probably the fitting mentioned in the

1601 inventory -- before continuing a stately progress to the

second floor and the magnificent great High Chamber.

This room is fit for a queen. The plasterwork frieze tells the

story of Diana the huntress -- a deliberate reference Queen

Elizabeth -- so it is possible that Bess intended that the room

be ready for a visit from her monarch. However, she herself sat

beneath the canopy with her feet on the footstool whilst her

attendants held court balanced on the needlework covered stools

around the room. The other significant feature is the Elizabeth

looking glass -- an expensive rarity. Clearly Bess had a sense

of her own importance and wanted other people to recognise her as

a wealthy and independent woman -- the queen of her own little

kingdom.

Duck through the door hidden by

tapestries to enter the Great Hall. Like the previous chamber,

it is carpeted by rush matting of the kind that Bess would have

recognised. The sweet smell of oats and meadowland lift the

atmosphere in these two rooms on the dreariest of days. The hall

is lined with portraits of Tudor, Jacobean and Carolinian

nobility. Mary Queen of Scots stares down at chattering school

children who gather beneath her picture. Her beauty is fading --

a consequence of her captivity. Despite the portrait and the

statue to the rear of the house, Mary never visited Hardwick.

There is only one piece of needlework in the hall that can be

directly ascribed to her, but it is well documented that in the

early days of Shrewsbury's wardenship Mary and Bess sat and

stitched together. Sadly the friendship withered as Mary grew

steadily more disquietened by Bess's overwhelming ambition and

the pressure of caring for the royal prisoner put a strain on the

Shrewsbury marriage best illustrated perhaps by the fact that the

earl is buried in Sheffield Cathedral whilst Bess -- ever the

builder -- is buried in Derby, commemorated by a monument of her

own design. Duck through the door hidden by

tapestries to enter the Great Hall. Like the previous chamber,

it is carpeted by rush matting of the kind that Bess would have

recognised. The sweet smell of oats and meadowland lift the

atmosphere in these two rooms on the dreariest of days. The hall

is lined with portraits of Tudor, Jacobean and Carolinian

nobility. Mary Queen of Scots stares down at chattering school

children who gather beneath her picture. Her beauty is fading --

a consequence of her captivity. Despite the portrait and the

statue to the rear of the house, Mary never visited Hardwick.

There is only one piece of needlework in the hall that can be

directly ascribed to her, but it is well documented that in the

early days of Shrewsbury's wardenship Mary and Bess sat and

stitched together. Sadly the friendship withered as Mary grew

steadily more disquietened by Bess's overwhelming ambition and

the pressure of caring for the royal prisoner put a strain on the

Shrewsbury marriage best illustrated perhaps by the fact that the

earl is buried in Sheffield Cathedral whilst Bess -- ever the

builder -- is buried in Derby, commemorated by a monument of her

own design.

Further along the great Hall is a picture of James I of England

as a young boy, and at the far end of the hall Queen Elizabeth I

keeps watch. Many of the other portraits are of Bess's family.

Her first marriage was childless; her second marriage was to an

older man who was smitten by her beauty and sold his estates to

buy land in Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire. This union was

probably Bess's happiest and it was the one that gave her

children. These children sired the lines of the Duke of

Devonshire, Newcastle and Portland. However, it was on her

grand-daughter Arbella Stuart that Bess pinned the hopes for her

family. It is also worth noting a portrait of an elderly

gentleman -- Thomas Hobbes -- was tutor to the 2nd and 3rd Dukes

of Devonshire. He died at Hardwick in 1679.

The tour continues through a warren of rooms with overmantels,

panels, distinctive furnishings and tapestries depicting

historical and mythical stories. The Green Velvet Room is large

and splendidly furnished with a massive 18th-century four-poster

bed. On the other side of this room is a tiny chamber that could

once be found in Chatsworth. When the old house at Chatsworth

was torn down to be replaced by the present house, this room was

dismantled and carted through the valleys of Derbyshire to

Hardwick. The room belonged to Mary Queen of Scots. In this

chamber stands the bed that she once slept in. It is very

heavily restored and there is no evidence to suggest that she

worked the designs on the hangings. Despite its change in

location there is no doubt that everything about the room is

authentic.

Pass through more winding corridors, down the North staircase --

a rather less grand wooden structure -- back to the first floor.

The dining room is ready for an 18th-century banquet. Further on

the drawing room has an 18th-century interior and displays family

photographs. As ever in this house the Hardwick stags are given

prominence. Look for the touching picture of a little girl in

Elizabeth dress. She is clutching her doll and staring through

the frame with a serious expression her face. This wide eyed

child in her richly embroidered dress with her gold necklace is

Lady Arbella Stuart.

At the time this portrait was painted Arbella was two

years old and her grandmother's delight. The cunning countess

had taken advantage of a meeting between her daughter Elizabeth

Cavendish and Charles Lennox (Lord Darnley's brother). The pair

had been married. Queen Elizabeth's wrath was so great that

Lennox's mother had been sent to the Tower. Somehow Bess managed

to escape similar punishment. Sadly for Arbella, she was orphaned

soon after her birth and passed into the care of Bess. Little

Arbella had a claim to the throne. The scene was set for a

tragedy. Bess was determined to capitalise on Arbella's heritage. At the time this portrait was painted Arbella was two

years old and her grandmother's delight. The cunning countess

had taken advantage of a meeting between her daughter Elizabeth

Cavendish and Charles Lennox (Lord Darnley's brother). The pair

had been married. Queen Elizabeth's wrath was so great that

Lennox's mother had been sent to the Tower. Somehow Bess managed

to escape similar punishment. Sadly for Arbella, she was orphaned

soon after her birth and passed into the care of Bess. Little

Arbella had a claim to the throne. The scene was set for a

tragedy. Bess was determined to capitalise on Arbella's heritage.

Arbella's bed chamber is a suite of rooms designed for a future

queen. Poor Arbella grew up in a confined atmosphere. She was

closely watched by her grandmother. She even slept in Bess's

room. For Arbella, Hardwick was a prison. Sadly Arbella escaped

into an inadvisable marriage and from there back into

imprisonment -- this time in the Tower of London on the orders of

James I, her cousin. The bonny little girl in the portrait

starved herself to death in 1615 after enduring years of

imprisonment. She is buried in Westminster Abbey with Mary Queen

of Scots; her aunt by marriage would have understood the mental

anguish of prolonged imprisonment.

Return through the house and down another set of stairs. A heady

aroma of food fills the air. Don't worry -- these are not the

ghostly manifestations of an old house. The kitchen with its

pewter plates, copper pans, kettles and scales has been

transformed into a restaurant serving locally inspired food. The

Bakewell tart and custard is a real treat, as is the treacle

sponge pudding that evokes cold winter evenings of childhood.

There's just as much to see outside the house. The gardens are

tranquil, lined with carefully maintained yew and holly hedges.

Wander through the herb garden and inhale the scents of mint,

thyme and lavender or admire brightly coloured tulips, irises,

poppies, roses and chrysanthemums, depending upon the season.

Continue along manicured avenues towards the house or relax in

the orchards. A small summerhouse provides a brief display

outlining the development of gardens four hundred years in the

making. A final garden at the back of the house mirrors the one

visitors first see on their entrance through the porters lodge.

The views lead towards an avenue of distant trees. Walk through

the opening in the hedge to take a closer look at the ha-ha. This

is a clever device to make it look as if the garden stretches out

into the surrounding countryside. The grazing sheep are

prevented from nibbling roses and borders by a wall that drops

into a ditch out of sight of the garden's genteel visitors.

It is also possible to visit the stone mason's yard. Hardwick

has its own quarry further down the hill. Find out how the grand

old house is maintained through the loving care of a team of

dedicated masons. And why not explore the parklands? Traces of

earthworks dating from the eleventh century can be seen in the

slopes below the hall, but as ever it is Bess's stamp that

dominates the scenery. Extensive ponds filled with water lilies

and wild life once provided the hall with a plentiful supply of

fish.

Virtually everything required for the building of Hardwick came

from Beth's estates; her self-sufficiency is well documented, so

why not round off the visit with a stop at Stainsby mill also

owned by the National Trust? A mill has stood on this site since

the Middle Ages. Its great waterwheel still turns the mill

stones and flour is still produced just as it once was for the

countess's tenants.

Before venturing to Stainsby don't forget to take a look at

the Old Hall. It is in the care of English Heritage. In Bess's

time it wasn't a ruin. She built upon and extended her childhood

home before beginning work on the new hall. The whole site was

one vast complex, the Old Hall housing servants and visitors.

Explore the empty rooms and climb the stairs to the chamber

containing the plasterwork figures of Gog and Magog. You'll be

following in the footsteps of Queen Victoria, who is said to have

surprised her entourage by reaching this point in the old

building before any of them.

Summer visitors wishing to make a full day of their excursion to

Hardwick can make use of the Heritage Coach Service -- a 1940's

bus -- which runs between Chesterfield, Bolsover Castle, Sutton

Scarsdale Hall, Stainsby Mill and Hardstoft Herb Garden on

Sundays, bank holidays and Thursdays. Other places to visit near

Hardwick include Chatsworth House and historic Chesterfield with

its famous twisting spire -- definitely worth a stop.

Visitors wishing to find out more about Mary Queen of Scots

should visit Wingfield Manor and Tutbury Castle. Chatsworth

House is much changed from the place Mary would have known

however her arbour and a hunting lodge may still be viewed here.

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Julia Hickey is passionate about England's heritage and particularly of Cumbria, where her husband comes from. In between dragging her family around the country to a variety of historic monuments, she works part-time as a senior lecturer at Sheffield Hallam University. She spends the rest of her week writing. In her spare time, she enjoys walking, dabbling in family history, cross-stitch, tapestry and photography.

Article © 2006 Julia Hickey; Photos © 2006 Adam Hewgill

|