Bateman's: Kipling's Sussex Jacobean Home

by Jean Bellamy

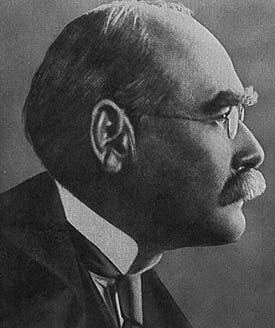

Years ago I had the privilege of being acquainted with a lady who

had been a governess to the children of Rudyard Kipling. Miss

Dorothy Ponton (or Dolly, as we knew her) subsequently became the

great man's private secretary, and at the time of her arrival at

'Bateman's', his famous Jacobean house near Burwash on the Sussex

Weald, he was 46 years of age. 'Short but well proportioned',

was how she described him, 'with a pronounced cleft in his chin,

his eye glowing through his spectacles beneath very dark bushy

eyebrows'. As well as teaching his daughter, Elsie, Miss Ponton

also coached his son, John, in Maths and English, her teaching

methods being quite unusual but very effective.

During her stay at 'Bateman's', Dorothy resided in Park Mill

Cottage, a converted hop-kiln separated from the garden proper by

a wooden gate. The cottage, which had a maid in attendance,

consisted of a small sitting room and kitchen with a bedroom

above, and was fronted by a well -- the sole source of water

supply. Sometimes the governess's duties took her abroad, as on

the occasion when she travelled to Switzerland where the family

were on holiday at Engleberg, so that John's coaching cold be

continued.

Sadly, and to his father's great grief, his son, who at 17 had

begged to be released from his studies to enter the army on the

outbreak of World War I, was killed at the Battle of Loos. He

was by then a 2nd Lieutenant in the newly-formed Second Battalion

Irish Guards, and his body was never recovered.

During the 1914-1918 war, Rudyard Kipling began to farm his own

land and bought some Guernsey cows. These successfully produced

Bateman's Baby, Bateman's Blizzard, Bateman's Bunting and

Bateman's Butterpat, amongst others. Some, to his great delight,

gained prizes at the Tunbridge Wells Cattle Show. In addition he

introduced a Sussex herd of red Shorthorns and two dray-horses,

the latter working on the farm to supplement the mechanical

appliances. There were piggeries too, which produced very

profitable litters, as well as a poultry farm and orchards

yielding good crops.

A new cottage behind Park Mill Cottage housed the gardener and

his wife who acted as dairymaid, and an elderly cowman occupied

Old Mill House. The latter, Sussex-bred and almost stone deaf

was nevertheless alert and always up betimes in the morning. His

speech was practically unintelligible to most folk, but the

reverse was also the case. After being given an order by Mrs.

Kipling which he appeared to have understood perfectly, two

minutes later he would tap on Miss Ponton's window and explain

apologetically, 'They do tawk so funny up theer. What do she

want?' Following which he would sidle up to her and place a very

large ear close to her mouth. When a calf was born he would

report the event with the words, 'Tell the master and the missus,

will'ee, she be a beauty!' -- regardless of the sex of the new

arrival.

In the summer of 1919, the Kipling's introduced a pedigree

bull, and as he appeared gentle enough, he was allowed to roam at

will in the pastures occupied by the Sussex herd. One morning

however, as the foreman's wife crossed the field to feed the

poultry, he tossed his head and followed her. Not liking his

demeanour, she promptly took to her heels and sought refuge in

one of the poultry-houses, much to the alarm of the inmates. The

playful beast then proceeded to trundle the poultry-house along

for some distance, his intermittent bellows in competition with

the shrieks of the foreman's wife and the cackling of the

terrified hens. Finally, angered by the noise, he charged in

real earnest, by which time the unaccustomed sight and sounds

having attracted the attention of some farm-labourers, he was

secured and condemned to solitary confinement.

At Harvest time, Bateman's Farm became a hive of industry, the

carting of the crops being performed by the dray-horses, Captain

and Blackbird. Captain had a sense of humour which sometimes led

him astray. One hot summer's day, Miss Ponton was returning to

her office when she came face to face with Captain trampling

around in the vegetable garden, his harness loose and jingling.

Before she could shut the gate, he pushed her aside with his nose

and plodded ponderously up the lane. A shout from one of the

farm-hands, from whom he had escaped during the dinner-hour,

reminded him of work so he jogged cheerfully on his way and tried

to dispose of his harness by rolling in a very muddy pond, much

to the alarm of the geese and ducks. Soon the enraged farm-hand

caught up with him, and at the crack of the whip, Captain stood

up. Finding that he was just out of reach of the lash, however,

and that his master had no intention of wetting his feet, he

remained standing in the cool water till working hours were

over.

Rudyard Kipling evinced a talent for

writing from his school days, and by his second year had begun to

make up verse -- chiefly limericks on his school-teachers and

fellow pupils. His headmaster advised him to take up journalism

and so it was that in the autumn of 1891, Kipling set sail for

Bombay (where he had been born on 30th December 1865), and

visited Lahore. Restlessness gave him a desire to see more of

the world and he travelled extensively, storing in his memory

information about the places he visited and the customs and

characters, information which proved useful to him in his future

writings. He owed his unusual Christian name to the place where

his father, John Kipling, first met his mother, Alice MacDonald,

on the shore of Lake Rudyard in Staffordshire. Rudyard Kipling evinced a talent for

writing from his school days, and by his second year had begun to

make up verse -- chiefly limericks on his school-teachers and

fellow pupils. His headmaster advised him to take up journalism

and so it was that in the autumn of 1891, Kipling set sail for

Bombay (where he had been born on 30th December 1865), and

visited Lahore. Restlessness gave him a desire to see more of

the world and he travelled extensively, storing in his memory

information about the places he visited and the customs and

characters, information which proved useful to him in his future

writings. He owed his unusual Christian name to the place where

his father, John Kipling, first met his mother, Alice MacDonald,

on the shore of Lake Rudyard in Staffordshire.

At the age of twenty-five, Kipling revealed himself as the future

Empire Poet, and was encouraged to continue his writing by Lord

Tennyson, the Poet-Laureate at that time. In 1907, he won the

Nobel prize for literature, and many of his writings were

amazingly prophetic, foretelling events long before they took

place. As he died three years before the outbreak of hostilities

in 1939, his verse on the subject of the Second World War is

quite remarkable.

The family had moved to 'Bateman's' from Rottingdean to escape

from the day-trippers who constantly peered through the windows

of their double-fronted Georgian rectory known as 'The Elms'. At

'Batemans', screened by a yew hedge from inquisitive eyes,

Kipling found privacy, and here he wrote 'If', 'Puck of Pook's

Hill' and 'The Glory of the Garden'.

'Bateman's' is now owned by the National Trust and is open to the

public (ground floor only). Kipling's rooms and study remain

just as they were during his lifetime, as do the gardens and

ground where may be seen the turbine he installed. One of the

oldest working water-driven turbines in the world., it stands

alongside the watermill grinding corn for flour. 'Batemans' may

be visited from April to the end of October.

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

|

Jean Bellamy has been writing since 1970, and is the author of over 300 published articles and short stories. She has written three children's novels (all with a "West Country flavour"). A resident of Dorset, she is the author of several local history books, including Treasures of Dorset, A Dorset Quiz Book, Second Dorset Quiz Book, Dorset Tea Trail, Dorset as she was spoke, Little Book of Dorset, 101 Churchces in Dorset, and Cornwall: A Look Back. Jean loves to explore and write on all things British.

|

Article © 2008 Jean Bellamy

(Originally published in Freelance Informer of Sutton, Surrey)

Bateman's photos courtesy of Britainonview.com; Kipling photo courtesy of Wikipedia.org

|