Wakes Weeks: From the Saints to the Sea

by Elizabeth Ashworth

It wasn't very long ago that the mill towns of Lancashire used to close down completely for a week or even a fortnight during the summer. Even today some shops, offices and factories still close for the local holiday, some newspaper deliveries cease and the schools 'break up' in time for the majority of the population to take their annual summer holiday.

In my home town of Blackburn, the wakes weeks holiday always begins on the third Saturday in July. Last year, for the first time, the schools did not begin their long summer break that weekend and the outcry and confusion that resulted was enormous -- resulting in many schools having only a fraction of their pupils present for the last week of term.

Many people believe that the wakes weeks began with the introduction of factory work, especially the cotton weaving mills, but in fact their origin lies much further back in history.

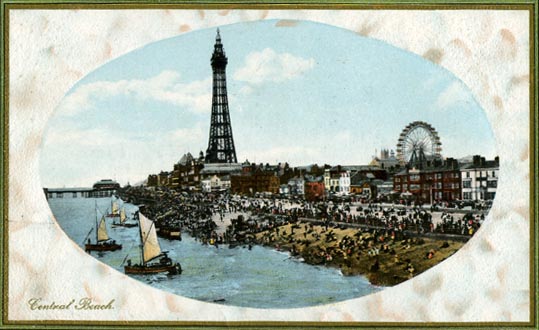

A postcard from Blackpool, prior to 1929 (when the Big Wheel was dismantled for not being exciting enough!)

Feasts of the Saints

The wakes have their beginnings in the middle ages. They were originally a religious festival when villagers would hold a feast of dedication of their local parish church. It is interesting that many of the usual saints to whom parish churches are dedicated have their feast days in the summer months: St Barnabas on 11th June, St John on 24th June, St Philip and St Paul on 29th June, St Thomas on 3rd July, St Christopher on 25th July, St Mary on 15th August and St Bartholomew on 24th August.

The name 'wakes' is the same as the one applied to funerals and refers to the custom of holding an all-night vigil in the church on the eve of the festival.

The main custom of the festival was the 'rushbearing', when all the old rushes that were strewn on the church's packed-earth floor were swept out and fresh ones were ceremoniously carried in. The rest of the day was then a holiday.

During the 16th century, the wakes holidays came under attack from the Puritan population, who had many strongholds in the Lancashire area. They disapproved of the drinking and revelling that took place and in 1571 the festivities were banned from churchyards in the archdiocese of York, which at that time included the county of Lancashire. Yet in 1633, King Charles 1 wrote:

"Of late, in some counties of our kingdom, we find that, under the pretence of taking away abuses, there hath been a general forbidding... of the feasts of the dedication of churches, commonly called wakes. Now our express will and pleasure is, that these feasts, with others, shall be observed... "

However, it was only a few years later that the civil war erupted and Oliver Cromwell and his puritan followers completely banned all festivities.

When the monarchy was restored in 1660, wakes and rushbearing festivals were quickly revived. In a description of the festival at Warton in North Lancashire where the church is dedicated to St Oswald whose saint's day falls on the 9th August, John Lucas, writing in the early 18th century, said:

"The feast of dedication... is now annually observed on the Sunday nearest to the first of August, and the vain custom of dancing, excessive drinking, etc., on that day being for many years laid aside, the inhabitants and strangers duly spend the day in attending the service of the church and preparing good cheer within the rules of sobriety in private houses... They cut hard rushes from the marsh, which they make up into long bundles, and then dress them in fine linen, ribbons, silk, flowers, etc.; afterwards the young women take the burdens upon their heads and begin the procession... which is attended with a great multitude of people, with music, drums, ringing bells and all other demonstrations of joy..."

But although this sounds very idyllic, the wakes holidays still drew much criticism for their drunkenness and unseemly behaviour, and in Rochdale in 1780 Dr Hind, a local vicar, forbade the rushes to be brought into his church.

The custom of rushbearing, however, did not die out. It thrived in many areas and also gave rise to the custom of morris dancing, when dancers became a part of the procession that followed the rushes to the church. It is still practised in some local churches today and in other areas of the country, notably Derbyshire, the festival is associated with well dressing.

The traditional wakes holiday too continued and often was accompanied by the arrival of a travelling fairground. Writing about Middleton in the 19th century, Samuel Bamford records that:

"On the Monday there began a fair of 'dealers in nuts, oranges and Eccles cakes... and shows, flying boxes(swing boats) and whirl-a-gigs'... "

The Rush to the Sea

Even with the coming of the industrial revolution the wakes survived because many workers simply didn't turn up when the traditional holiday came. So mill owners decided that they might as well close their factories down for a few days at this time to allow them to clean and overhaul the machinery.

With the coming of the railways in Victorian times, the traditional wakes weeks were when millworkers would travel to seaside resorts like Blackpool for their annual holiday. The whole of one town and its surrounding area would grind to a halt and the workers would all board the trains for the coast. Resorts such as Blackpool -- and for the slightly more discerning, Morecambe -- would be filled with holidaymakers. Families and whole streets of people would simply move their lives from the grimy industrial cotton towns to the coast for one week of the year. The wakes festivities and fairs continued in Blackpool with the building of the Big Wheel and the Pleasure Beach, the greatest wakes fair of all! In 1884 an article in the Pall Mall Gazette describes the arrival of holiday makers in Blackpool.

"Every train brings crowds of them, with huge carpet bags, tin boxes and bundle handkerchiefs... It is the habit of half a dozen families to go to the seaside together, and take tea at each other's lodgings."

It was because of this overwhelming exodus of people to the seaside that neighbouring towns grew into the habit of holding their wakes weeks holiday at different times. Blackpool simply could not have accommodated the whole of Lancashire in one week.

Even with the decline of the cotton industry, the holidays of Lancashire towns continue in their traditional pattern. The schools in Burnley still begin their summer holiday two weeks before the schools in Blackburn. The Darwen schools used to begin their holiday a week before Blackburn and it was only after government re-organisation a few years ago that the school holidays of the neighbouring towns now coincide.

Some people believe that the wakes weeks have now outlived their usefulness and should be consigned to history, but a tradition that has continued for so long will not be easy to push aside. In Blackburn at least, there continues to be a holiday feeling throughout the town during the last two weeks in July, and this year the schools will close in time to enjoy it.

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Elizabeth Ashworth writes fiction and nonfiction for both adults and children. Her short stories have appeared in such publications as Christian Herald, People's Friend, Take a Break Fiction Feast, My Weekly and Parentcare; her nonfiction has appeared in a variety of magazines, including The Lady, Lancashire Life and My Weekly. She is also a regular contributor to Lancashire Magazine. Her books include Champion Lancastrians (Sigma Press, 2006) and Tales of Old Lancashire (Countryside Books, 2007); she is currently working on a book on Lancashire Graves, and a novel titled "The De Lacy Inheritance."

Article © 2005 Elizabeth Ashworth

|