England Expects: Nelson and the Battle of Trafalgar

by Dawn Copeman

Thanks to ABBA, we all know that in 1815 "at Waterloo Napoleon did surrender", yet in Britain the Battle of Trafalgar is the most celebrated of the Napoleonic battles. So why do the British make such a big deal of Trafalgar? Well, firstly, it was at the close of this battle that a national hero, Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson, died. Secondly, the Battle of Trafalgar secured for Britain supremacy of the seas and ensured that the French could not proceed with their intended invasion of Britain.

Yes, you read that right. In 1804 when Napoleon crowned himself Emperor of the French he also drew up plans for an invasion of Britain and assembled his "Army of England" at Boulogne. Napoleon tried to invade England on several occasions, but was thwarted each time. The first attempt in February 1804 was abandoned due to a royalist plot against Napoleon. The second planned invasion in summer 1804 was cancelled when Admiral Latouche-Treville, the commander of the French fleet in Toulon, died and had to be replaced with Admiral Pierre de Villeneuve. The third planned invasion early in 1805 failed due to bad weather.

It was because of the threat of a French invasion that the 74 Martello Towers that line the South Coast of England -- from Folkestone to Seaford -- were constructed. The towers were built every quarter of a mile except where cliffs protected the coast. They were named after the Tower of Mortella in Corsica which, despite being manned by only 38 men, survived an attack by two ships and a detachment of troops in 1794.

Napoleon was determined to invade Britain in 1805, but many of his fleets had been blockaded in their ports by the British fleets. So he tried to lure the British out to the east, which would enable his fleets to escape and converge on Britain. Whilst he was a brilliant military strategist, however, he was no naval man and had no real understanding of naval warfare. He expected his ships to be at specific locations by certain dates and made no allowances for winds or for the British fleet anticipating his moves. Thus in reality his elaborate plans were impractical. Napoleon was determined to invade Britain in 1805, but many of his fleets had been blockaded in their ports by the British fleets. So he tried to lure the British out to the east, which would enable his fleets to escape and converge on Britain. Whilst he was a brilliant military strategist, however, he was no naval man and had no real understanding of naval warfare. He expected his ships to be at specific locations by certain dates and made no allowances for winds or for the British fleet anticipating his moves. Thus in reality his elaborate plans were impractical.

Nevertheless Nelson was kept busy throughout most of 1805 chasing the French fleet around the Mediterranean. In fact Nelson had been at sea almost continuously from 1803 to 1805, a mammoth achievement considering the lack of British bases at which to take on supplies. This alone helped to raise Nelson's profile amongst the normal British population, as this letter to Nelson from Hugh Elliot of Naples shows: "to have kept your ships afloat, your rigging standing, and crews in health and spirits is an effort such as was never realized in former times, nor I doubt, will ever again be repeated by any other admiral. You have protected us for two long years, and you have saved the West Indies."

Nelson was renowned for ensuring the health and welfare of his men. He insisted that all sailors suck lemons, oranges or limes every day to prevent scurvy -- which is why British sailors were known as limeys. And he was very good at keeping their morale up -- all this despite suffering almost continuously from sea-sickness, an ailment he was determined not to let stand in the way of his naval career. That career was an odd choice for a son of a Norfolk village parson!

Horatio Nelson was born on the 29th September 1758 in the village of Burnham Thorpe in Norfolk. He entered the navy in 1770 aged just twelve and progressed quickly through the ranks. He was made admiral in 1797. Nelson paid dearly for his rank: he lost his right eye at Corsica in 1794, suffered an internal rupture at St Vincent in February 1797, lost his right arm at Tenerife in July, and finally suffered a head wound in 1798 during the Battle of the Nile.

Some historians believe this head wound caused a mental imbalance in Nelson that resulted in his affair with Lady Emma Hamilton. She was the wife of Sir William Hamilton, the British representative at the court of Naples. A confidant of Queen Maria Carolina, Emma managed to ensure that Nelson's ships had supplies before the Battle of the Nile. From then on, Nelson was captivated by her. He went on to father two daughters with her whilst remaining married to Frances Nisbet, whom he had married in 1787 but with whom he had no children. Some historians believe this head wound caused a mental imbalance in Nelson that resulted in his affair with Lady Emma Hamilton. She was the wife of Sir William Hamilton, the British representative at the court of Naples. A confidant of Queen Maria Carolina, Emma managed to ensure that Nelson's ships had supplies before the Battle of the Nile. From then on, Nelson was captivated by her. He went on to father two daughters with her whilst remaining married to Frances Nisbet, whom he had married in 1787 but with whom he had no children.

The affair scandalized British society and for a short while Nelson was out of favour with the population. But his success at winning the Battle of the Nile in 1798, followed by the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801, not only brought him honours from King George III, but also forgiveness from the British population. Nelson was made a baron after the Battle of the Nile and a Viscount after the Battle of Copenhagen

By 1805, because of his relentless hunt for Napoleon's fleets, Nelson was more popular than ever and considered to be the hero of the hour. As Nelson himself commented "I had their huzzas before, I have their hearts now!"

Meanwhile, Napoleon had become impatient with Villeneuve's failures to meet deadlines and decided to replace him with Admiral Rosily. Villeneuve had reached Cadiz in Spain in August 1805, where he hoped to repair his ships and take on fresh supplies. His ships were allowed into Cadiz by Admiral Collingwood, who only had three ships with which to blockade the port. Villeneuve was doubly unlucky: firstly, an epidemic had just raged through Cadiz and no supplies were forthcoming until a direct order came from Madrid; and secondly, no sooner had he begun to re-stock his ships than he received Napoleon's orders to leave Cadiz at once. By the time this order had arrived, so had Nelson on the 100-gunned HMS Victory with the rest of the British fleet.

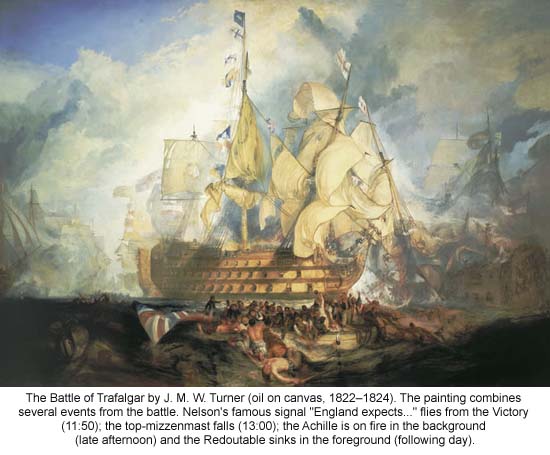

Nelson knew now that battle was inevitable. He spent hours with the commanders of his fleet, explaining to them in intricate detail how the battle would be fought. Normally naval battles of that time consisted of two lines of ships facing each other and firing their guns at one another. Since the fleet consisted of 22 ships of the line (big, gunned sailing ships) and six frigates, it could take a whole day just to get the ships into fighting position. Nelson preferred to sail in the order of battle and to get as close as possible to the enemy. This tactic, known by the British fleet as the Nelson Touch, was to cut the French line into three parts and then use his entire fleet to attack half the French fleet and destroy or capture the ships before the remainder of the French fleet could turn around and join battle.

Unfortunately for Villeneuve, the French fleet of 33 ships included 15 Spanish ships, which had been given orders to assist the French but were not under his direct command. It was difficult enough for Villeneuve to get the Spanish to agree on the order of sail, never mind battle tactics. Villeneuve had been present at the Battle of the Nile, when the Nelson Touch had first been used in a sea battle. He warned his captains not to expect a straightforward line battle but told them "he will try to double our rear, cut through the line and bring against the ships thus isolated groups of his own to surround and capture them." Fortunately for us, but not for them, no-one listened to him.

Nelson went through his plan constantly in the days leading up to battle to ensure that everyone knew exactly what to do. He summed it up by saying "In case Signals can neither be seen nor perfectly understood, no Captain can do very wrong if he places his ship alongside that of an Enemy." Villeneuve issued his captains with a similar sounding call: "The captain who is not in action is not at his post."

On 19 October 1805, British frigates reported that the French fleet was on the move and heading for Gibraltar. Nelson set sail immediately and by the 20th he lay in wait for them midway between Cape Trafalgar and Cape Spartel. The French had had difficulty leaving Cadiz due to poor winds and didn't arrive until the early hours of the 21st of October. When he saw the British fleet waiting for him, Villeneuve signalled for a change of course; seeing this, Nelson gave the orders for immediate attack, worried that the French might escape. The signal ended with Nelson's famous rousing words, "England expects that every man will do his duty."

These weren't however, Nelson's actual words. The original words were "England confides (i.e. has confidence) that every man will do his duty", but 'confides' was not in the code book and therefore would have to have been spelled out, which would take time. 'Expects', however, was in the code book and so the message was changed.

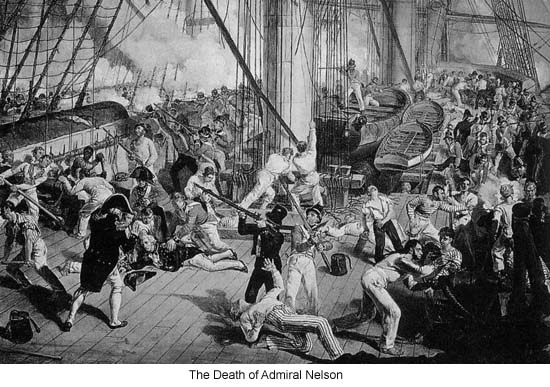

The battle began at midday when Admiral Collingwood's ship, the Royal Sovereign, sailed in close to the French fleet. All the British ships engaged in close battle or "pell mell", and it was at 13.15, whilst the Victory was in close battle with the Redoutable, that Nelson was hit by a marksman from the mizzentop of the French ship. He was hit in the chest and the ball lodged in his spine. He was carried below decks and died three hours later. The battle ended shortly after at 5pm.

The combined French and Spanish fleet lost 18 ships and over 5800 lives, and 20,000 of them were taken prisoner. The British lost 1690 lives, but suffered no loss of ships.

Nelson was given a state funeral at St. Paul's Cathedral and a posthumous earldom. Trafalgar is now recognised as an epic sea battle and Nelson as an outstanding leader and tactician and every year on the 21st October, Britain and particularly the Royal Navy celebrate Trafalgar Day.

HMS Victory, now moored at the Historic Dockyard in Portsmouth, is still on the navy roll, which means it is still on active service, is still maintained by the Navy and still has sailors posted to it.

Related Articles:

- Horatio Nelson: A Norfolk Hero, by Zoe King

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/country/nelson.shtml

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Dawn Copeman is a freelance writer and commercial writer who has had more than 100 articles published on travel, history, cookery, health and writing. She currently lives in Lincolnshire, where she is

working on her first fiction book. She started her career as a freelance

writer in 2004 and has been a contributing editor for several publications, including TimeTravel-Britain.com and Writing-World.com .

Article © 2005 Dawn Copeman

Photos courtesy of Wikipedia.org

|