A History of Britain in Its Pub Signs

by Elaine Saunders

As far as

time-travel goes, a walk down any High Street in Britain can take

an explorer back across centuries. As far as

time-travel goes, a walk down any High Street in Britain can take

an explorer back across centuries.

Few people realise that two thousand years of history is hanging

over their heads, and that the humble pub sign can hold the key

to a town's past. Pubs were rarely named by accident but were

inspired by religion, royalty, heroes and the occasional scandal.

Knowing how to read the signs means that any visitor can

unlock the history of the inn and learn a great deal about its

former customers.

When the Romans invaded Britain in AD43 they brought hot baths,

straight roads and the first real pubs with them. In Rome,

landlords of these tabernae hung bunches of vine leaves

outside as a simple sign but, upon reaching Britain, they had to

improvise. They used any evergreen plant and it's still possible

to find pubs called The Bush or The Hollybush up

and down the country.

Roman roads such as Fosse Way and Ermine Street opened up Britain

to long-distance travel and large numbers of troops moving around

the country needed to be fed and watered along the way. Roadside

inns opened at regular stages -- much like today's motorway

service stations -- where travellers could find food, drink and

sometimes a bed for the night. Modern roads still follow the

route of these ancient highways and it's not inconceivable that

some of the roadside inns have been on the same site for

centuries.

By the 12th Century large groups were once more taking to the

roads, this time in pursuit of pilgrimage. Following the murder

of Thomas à Beckett in Canterbury, pilgrimages to his

shrine, and other cathedrals around the country, became

fashionable. One such journey was described by Chaucer in his

Canterbury Tales in which pilgrims set out from the

Tabard in London, a real inn of the time.

Traditionally, travellers sought overnight accommodation in the

many monasteries along the way but the numbers became so great

that the monks could no long cope with the influx. Enterprising

locals therefore set up private inns and took religious names to

imply a monastic connection. However, the population was largely

illiterate so pictorial signs were used to advertise the inns

instead of lettering. The images were probably copied from

churches' stained glass windows -- the pictures of saints, angels

and arks being both familiar and easy to reproduce.

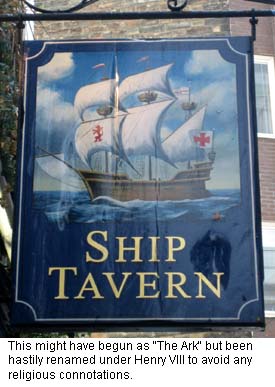

These religious influences

on British pub names would have continued indefinitely had Henry

VIII not been desperate for a male heir. Realising that Catherine

of Aragon could not give him a son, he sought to divorce her and

marry Anne Boleyn. When the Pope refused, Henry broke from the

Catholic faith and established his new Church of England in the

16th Century. He systematically destroyed the monasteries and

confiscated their wealth whilst pubs rushed to change their names

to eradicate any Catholic links. Arks became Ships

and St Peter, the guardian of the gates of Heaven,

became the Crossed Keys. Many more landlords played safe

by adopting loyal names like the Kings Arms or Kings

Head. These religious influences

on British pub names would have continued indefinitely had Henry

VIII not been desperate for a male heir. Realising that Catherine

of Aragon could not give him a son, he sought to divorce her and

marry Anne Boleyn. When the Pope refused, Henry broke from the

Catholic faith and established his new Church of England in the

16th Century. He systematically destroyed the monasteries and

confiscated their wealth whilst pubs rushed to change their names

to eradicate any Catholic links. Arks became Ships

and St Peter, the guardian of the gates of Heaven,

became the Crossed Keys. Many more landlords played safe

by adopting loyal names like the Kings Arms or Kings

Head.

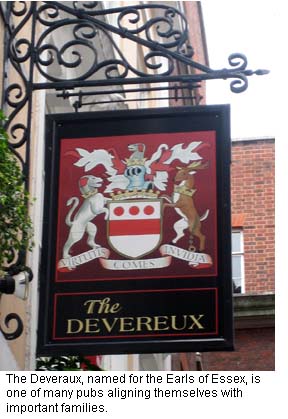

Henry VIII sold off the monastery lands to the highest bidder and

granted peerages to his supporters so some landlords aligned

themselves with the new incoming lord of the manor, giving us

names like the Devereux Arms or the Duke of

Norfolk.

The king was also a great sportsman, a fact celebrated in pub

signs. Near hunting grounds there are plenty of pubs called

The Greyhound (Henry's favourite hunting dog) or The

Bird in Hand for his love of falconry. Other common sporting

signs include the Fox & Hounds, Dog & Duck or

Hare & Hounds.

Landlords soon realised that pub signs could also advertise the

entertainment on offer. Ye Olde Fighting Cocks in St

Albans is a perfect example and claims to be the oldest pub in

Britain. It used to be the dovecot for St Albans Abbey but after

the Dissolution of the Monasteries, a clever businessman realised

its circular shape would make it the perfect venue for

cock-fighting. Many pubs with cock in the title would have

held cock fights whilst the Bull advertised bull-baiting

and the Bear bear-baiting.

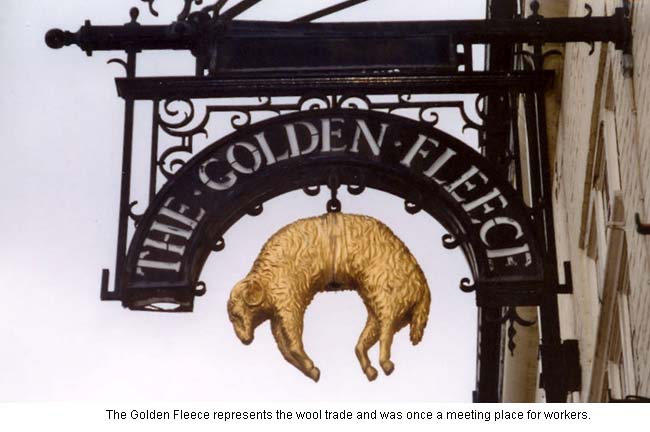

Yet more pubs associated themselves with the area's predominant

trade as a way of gathering custom, such as the Golden

Fleece (for the local wool trade). Bricklayers,

Blacksmiths and Carpenters Arms were meeting places

for local tradesmen and often acted as unofficial employment

exchanges. A craftsman moving to the area would seek out such a

pub where the landlord could introduce him to an employer or

extend credit until he established himself in business.

Landlords regularly offered banking services to customers and

allowed employers to pay their workers on the premises. By the

18th century, the larger inns on stage-coach routes had become

sophisticated commercial centres with strong rooms, storage

facilities and lines of credit for businessmen.

Pub signs now began advertising the services on offer to the

hundreds of passenger coaches and commercial vehicles. Coach

& Horses, Horse & Groom, Wheelwrights and Farriers

Arms sprang up along the major routes. It's easy to recognise

a former coaching inn as many still have high arches from the

street to the stable-yard behind, where grooms, porters,

coach-repairers and blacksmiths worked hard to keep traffic

moving.

However, not only the

tavern owners flourished -- highwaymen made the most of the rich

pickings and are occasionally remembered on pub signs. One such

was Lady Katharine Ferrers of Markyate, Hertfordshire, who turned

to highway robbery out of boredom and to repay her gambling

debts. She preyed on the main London to Birmingham road,

relieving one traveller of today's equivalent of £60,000.

Most highwaymen would kill for a few coins, however. The

Wicked Lady at Wheathampstead, Hertfordshire, stands on

the spot where she was fatally wounded in 1660. However, not only the

tavern owners flourished -- highwaymen made the most of the rich

pickings and are occasionally remembered on pub signs. One such

was Lady Katharine Ferrers of Markyate, Hertfordshire, who turned

to highway robbery out of boredom and to repay her gambling

debts. She preyed on the main London to Birmingham road,

relieving one traveller of today's equivalent of £60,000.

Most highwaymen would kill for a few coins, however. The

Wicked Lady at Wheathampstead, Hertfordshire, stands on

the spot where she was fatally wounded in 1660.

The Industrial Revolution brought untold wealth to Britain and

commercial traffic increased hugely. Industrialists abandoned the

roads and built canals to carry coal and raw materials to their

factories. Pubs like the Waterway or the Navigation

were built along the banks to serve the watermen, many of whom

lived on their boats with their families. But by 1850, the

faster, cheaper railways had superseded the canals and every town

soon boasted its Railway Tavern or Station Arms.

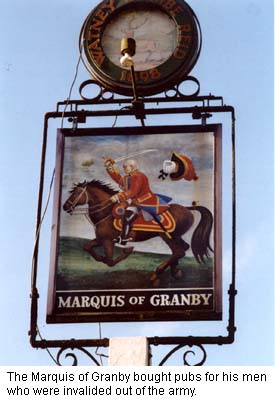

Pub signs have also been used as affectionate tributes and

commemoration. Heroes like Nelson and Wellington

have pubs named after them, as do famous battles, ships and naval

engagements. One affectionate tribute is reserved for the

Marquis of Granby, a British army commander much loved by

his men. In the 18th century there were no army pensions and,

rather than let his men starve, he bought pubs for every one of

his disabled non-commissioned officers. He died over

£37,000 in debt (£4million today) but the many pubs

bearing his name are a fond memorial.

Pubs are a familiar sight in town and country but many of

the names crop up more often then others. Every town has its own

Crown, Red Lion and Royal Oak but what's the

particular history behind them? Why are they so popular? Pubs are a familiar sight in town and country but many of

the names crop up more often then others. Every town has its own

Crown, Red Lion and Royal Oak but what's the

particular history behind them? Why are they so popular?

Compared with many of Britain's pub names, The Crown is

relatively new, having become popular as late as 17th century. At

that time, King Charles I's disputes with Parliament had spilled

over into civil war, the Parliamentary army being commanded by

Oliver Cromwell. Despite fleeing to Scotland, King Charles was

eventually captured, tried and executed in 1649, his son was

exiled and Cromwell assumed power.

Cromwell was a Puritan and deeply religious, and he effectively

prohibited most forms of enjoyment. Pubs and theatres closed,

sports were banned and colourful clothing and cosmetics were

forbidden. The country wore black, as if in mourning for the

entertainments it had once enjoyed and even Christmas was

outlawed.

Cromwell's death and the restoration of King Charles II heralded

a new era of indulgence. Theatres reopened for the performance of

the new, bawdy, comic Restoration plays whilst ale flowed in

taverns once more. Landlords were so relieved at the return to

business that pubs were renamed The Crown in Charles'

honour.

Crown also appears in another popular name -- Rose

& Crown. There are two theories behind this name, the

first coming from another civil war, the Wars of the

Roses. Sibling rivalries in the 14th century lead to war

between the houses of Lancaster (whose supporters wore red roses)

and York (who wore white). In the Battle of Bosworth in 1485,

Lancastrian Henry Tudor defeated and killed the Yorkist King

Richard III and crowned himself Henry VII. He then married the

old king's beautiful niece, Elizabeth the Rose of York, and they

went on to found the great Tudor dynasty. Pubs were named in the

couple's honour, Rose & Crown.

The last Tudor monarch, Elizabeth I, may

unwittingly have influenced the second explanation of this name.

When she died, she appointed King James of Scotland as her heir.

It is said that pubs called the Crown added an English

rose to their signs, implying that their loyalty to a Scottish

king must always take second place to their Englishness. The last Tudor monarch, Elizabeth I, may

unwittingly have influenced the second explanation of this name.

When she died, she appointed King James of Scotland as her heir.

It is said that pubs called the Crown added an English

rose to their signs, implying that their loyalty to a Scottish

king must always take second place to their Englishness.

The Tudors may also have influenced the next pub sign, the

Swan. Anne of Cleves, the fourth wife of Henry VIII, had a

white swan as her family crest and pubs are said to have adopted

this name as a tribute to her. As the marriage was annulled after

six months however, it's unlikely to be the true explanation.

Henry IV's wife, Mary de Bohun of Hereford, also had a white swan

in her coat of arms, as did Margaret of Anjou, wife of Henry VI.

However, this sign could easily have been connected with the

ancient trade guilds. The reigning monarch still owns all swans

on open water but, in the 15th Century, the Worshipful Companies

of Dyers and of Vintners were both granted rights of ownership.

The Swan could have been a meeting place for workers in

either of these trades. Roasted swan was also served at

ceremonial banquets so a pub by this name could have implied fine

dining.

As well as royal associations, many pub names have religious

connections. Masons building a church would have stayed at the

local inn and many took an ecclesiastical name upon completion.

The ones rebuilding St Brides church after the Great Fire of

London stayed in the Old Bellin Fleet Street. Bells were

believed to have magical powers, protecting against evil spirits

and lightning. Before today's urban noise, bells ringing out to

summon the faithful to prayer or sounding curfew would have been

far more noticeable. No wonder names like Bell, Old Bell, Six

Bells and Eight Bells are so often seen.

The ark has also been symbol of the church: a ship's masts are in

the shape of a cross and the centre of the church is the

nave, which comes from the same word root as

navigation. When Henry VIII renounced the Catholic faith

in the 16th Century to create his new Church of England, many

pubs abandoned names implying Catholic allegiance. Kings Head

or Kings Arms suddenly became very popular and any pub

called the Ark could have become the Ship.

However, a ship was also a very easy image for

signwriters to draw and would also have been popular in coastal

areas or naval ports.

Some ships even had pubs named after them, like the Royal

George, which sank in 1782 with massive loss of life, or the

Royal Oak, torpedoed in the first weeks of World War II

with 833 fatalities.

Most pubs called the Royal Oak

usually show a painting of a tree with a crown resting in the

branches. This takes us back once more to the English Civil War

when the future Charles II was on the run from Cromwell's army.

He remained undiscovered for a day in the branches of an oak tree

in Boscobel wood, even though Cromwell's men were on ground

below. On Charles II's restoration, this became a popular story

and a great number of pubs took the name. Most pubs called the Royal Oak

usually show a painting of a tree with a crown resting in the

branches. This takes us back once more to the English Civil War

when the future Charles II was on the run from Cromwell's army.

He remained undiscovered for a day in the branches of an oak tree

in Boscobel wood, even though Cromwell's men were on ground

below. On Charles II's restoration, this became a popular story

and a great number of pubs took the name.

A far less popular king was George IV, who reigned from 1820 to

1830, and lived an excessively extravagant lifestyle. He was

hugely overweight, addicted to laudanum and father of several

illegitimate children. He married Caroline of Brunswick to

discharge his debts but was hateful to her and they separated

within a year of marriage. He was once described by the Duke of

Wellington as "selfish, ill tempered and without one redeeming

quality." It's strange therefore that there should be so many

pubs called the George showing a handsome Regency dandy on

their signs.

Another figure widely disliked was John of Gaunt, the fourth son

of Edward III and the richest man in England in the 14th Century

(his annual income exceeded £5 million at today's rates).

He founded the House of Lancaster, was part of the feud that led

to the Wars of the Roses and crushed the Peasants' Revolt of

1381. It's highly unlikely therefore that he inspired the Red

Lion so often seen.

Another theory is that James I decreed that the Red Lion

of Scotland should be displayed outside all public buildings, but

that would surely have lead to almost every pub adopting the

name. In fact, lions were a popular heraldic device in black,

blue, red, gold and white, and all have appeared on pub signs.

Landlords might have given their pubs the name Red Lion to

gain the patronage of the local lord, or a dignitary with this

crest could have visited the inn at one time.

The final sign is connected with neither religion nor royalty but

was inspired by the Victorians' love of innovation. The

Industrial Revolution brought economic and technological success

to Britain, and in the 1830s the construction of a vast railway

network began. Soon most towns in the country had a station, and

hotels were built to cater for the new passengers. Like those on

the old coaching routes, the pubs took names like the Railway

Tavern or Station Arms as a way of attracting the

travelling public.

Defining the origins of pub names is not an exact science because

history is open to a great deal of interpretation (and

misinterpretation). However, pub signs are like snapshots from

time, every one of them capturing an historical event or era.

These pictures have been handed down to us across the centuries

and carry these stories forwards even if, most of the time, the

stories literally pass over our heads.

Pub signs are collectively a unique record of Britain's history

-- religious, industrious and scandalous. Many are also

beautifully-crafted works of art on public view. So the next time

you're walking down the High Street, make sure you stop, look up

and read the signs. There's a world of stories hanging over your

head.

Related Articles:

- The Historic Pubs of London, by Pearl Harris

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/london/pubs.shtml

- Haunted Pubs of England, by Dr. Gareth Evans

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/history/hauntedpubs.shtml

- A Beginner's Guide to British Pubs, by Graham Hughes

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/travel/pubs.shtml

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

|

Elaine Saunders is a freelance writer based near London. Find out more about the history of pubs and pub names in her e-book, A Book About Pub Names, which contains over 100 illustrations together with dozens of links to specialist websites. It's a comprehensive guide to the history of Britain's pubs and pub signs with chapters on their history, old trades and occupations and drinking measures.

|

Article and photos © 2008 Elaine Saunders

|