The Canterbury Tales

The Canterbury Tales is a collection of stories written by

Geoffrey Chaucer in the 14th century (two of them in prose, the

rest in verse). The tales, some of which are originals and others

not, are contained inside a frame tale and told by a group of

pilgrims on their way from Southwark to Canterbury to visit the

shrine of Saint Thomas à Becket at Canterbury Cathedral.

The Canterbury Tales are written in Middle English.

The themes of the tales vary, and include topics such as

courtly love, treachery and avarice. The genres also vary, and

include romance, Breton lai, sermon, and fabliau. The characters,

introduced in the General Prologue of the book, tell tales of

great cultural relevance.

Some of the tales are serious and others humorous; however,

all are very precise in describing the traits and faults of human

nature. Religious malpractice is a major theme as well as

focusing on the division of the three estates. Most of the tales

are interlinked with similar themes running through them and some

are told in retaliation for other tales in the form of an

argument. The work is incomplete, as it was originally intended

that each character would tell four tales, two on the way to

Canterbury and two on the return journey. This would have meant a

possible 120 tales, which would have dwarfed the 26 tales

actually written.

People have sought political overtones within the tales,

particularly as Chaucer himself was a significant courtier and

political figure at the time, close to the corridors of power.

There are many hints at contemporary events, although few are

proven, and the theme of marriage common in the tales is presumed

to refer to several different marriages, most often those of John

of Gaunt. Aside from Chaucer himself, Harry Bailly of the Tabard

Inn was a real person and the Cook has been identified as quite

likely to be Roger Knight de Ware, a contemporary London

cook.

The Canterbury Tales can also tell modern readers much

about "the occult" during Chaucer's time, especially in

regards to astrology and the astrological lore prevalent during

Chaucer's era. There are hundreds if not thousands of

astrological allusions found in this work; some are quite overt

while others are more covert in nature.

The idea of a pilgrimage appears to have been mainly a useful

device to get such a diverse collection of people together for

literary purposes. The Monk would probably not be allowed to

undertake the pilgrimage and some of the other characters would

be unlikely ever to want to attend. Also all of the pilgrims ride

horses, there is no suggestion of them suffering for their

religion. None of the popular shrines along the way are visited

and there is no suggestion that anyone attends mass, so that it

seems much more like a tourist's jaunt.

Chaucer does not pay that much attention to the

progress of the trip. He hints that the tales take several days

but he does not detail any overnight stays. Although the journey

could be done in one day this speed would make telling tales

difficult and three to four days was the usual duration for such

pilgrimages. The 18th of April is mentioned in the tales and

Walter William Skeat, a 19th century editor, determined 17 April

1387 as the probable first day of the tales. Chaucer does not pay that much attention to the

progress of the trip. He hints that the tales take several days

but he does not detail any overnight stays. Although the journey

could be done in one day this speed would make telling tales

difficult and three to four days was the usual duration for such

pilgrimages. The 18th of April is mentioned in the tales and

Walter William Skeat, a 19th century editor, determined 17 April

1387 as the probable first day of the tales.

The work was begun some time in the 1380s with Chaucer stopping

work on it in the late 1390s. It was not written down fully

conceived: it seems to have had many revisions with the addition

of new tales at various times. The plan for 120 tales is from the

general prologue. It is announced by Harry Bailly, the host, that

there will be four tales each. This is not necessarily the

opinion of Chaucer himself, who appears as the only character to

tell more than one tale. It has been suggested that the

unfinished state was deliberate on Chaucer's part.

The structure of The Canterbury Tales is easy to find in

other contemporary works, such as The Book of Good Love by

Juan Ruiz and Boccaccio's Decameron, which may have been

one of Chaucer's main sources of inspiration. Chaucer indeed

adapted several of Boccaccio's stories to put in the mouths of

his own pilgrims, but what sets Chaucer's work apart from his

contemporaries' is his characters. Compared to Boccaccio's main

characters -- seven women and three men, all young, fresh and

well-to-do, and given Classical names -- the characters in

Chaucer are of extremely varied stock, including representatives

of most of the branches of the middle classes at that time. Not

only are the participants very different, but they tell very

different types of tales, with their personalities showing

through both in their choices of tales and in the way they tell

them.

It is sometimes argued that the greatest contribution that this

work made to English literature was in popularising the literary

use of the vernacular language, English (rather than French or

Latin). However, several of Chaucer's contemporaries -- John

Gower, William Langland, and the Pearl Poet -- also wrote major

literary works in English, making it unclear how much Chaucer was

responsible for starting a trend rather than simply being part of

it.

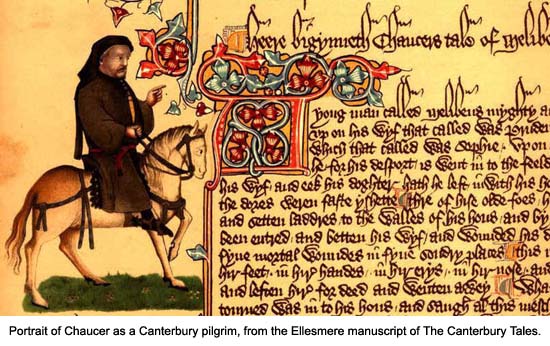

Two early manuscripts of the tale are the Hengwrt manuscript and

the Ellesmere manuscript. Altogether, the Tales survives in 84

manuscripts and four printed editions dating from before 1500.

In 2004, Professor Linne Mooney was able to identify the

scrivener who worked for Chaucer as an Adam Pinkhurst. Professor

Mooney, working at the University of Cambridge, was able to match

Pinkhurst's signature on an oath he signed to his lettering on a

copy of The Canterbury Tales that was transcribed from Chaucer's

working copy.

Scholars divide the tales into ten fragments. The tales that make

up a fragment are directly connected, usually with one character

speaking to and handing over to another character, but there is

no connection between most of the other fragments. This means

that there are several possible permutations for the order of the

fragments and consequently the tales themselves. The listing

below is perhaps the most common in modern times. It is assumed

that Chaucer would have amended his manuscript or inserted more

tales to fill the time.

The Tales:

- The General Prologue

- The Knight's Tale

- The Miller's Prologue and Tale

- The Reeve's Prologue and Tale

- The Cook's Prologue and Tale

- The Man of Law's Prologue and Tale

- The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale

- The Friar's Prologue and Tale

- The Summoner's Prologue and Tale

- The Clerk's Prologue and Tale

- The Merchant's Prologue and Tale

- The Squire's Prologue and Tale

- The Franklin's Prologue and Tale

- The Physician's Tale

- The Pardoner's Prologue and Tale

- The Shipman's Tale

- The Prioress' Prologue and Tale

- Chaucer's Tale of Sir Topas

- The Tale of Melibee

- The Monk's Prologue and Tale

- The Nun's Priest's Prologue and Tale

- The Second Nun's Prologue and Tale

- The Canon's Yeoman's Prologue and Tale

- The Manciple's Prologue and Tale

- The Parson's Prologue and Tale

- Chaucer's Retraction

Related Articles:

- Canterbury: Still the Perfect Pilgrimage!, by Julia Hickey

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/towns/canterbury.shtml

- Canterbury Cathedral, by John P. Seely

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/churches/canterbury.shtml

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Article reprinted from Wikipedia.org

|