Thomas Becket: Canterbury's Martyred Saint

St Thomas Becket (December 21, 1118 - December

29, 1170) was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1162 to 1170. He

engaged in a conflict with King Henry II over the rights and

privileges of the Church and was assassinated by followers of the

king in Canterbury Cathedral. He is also commonly known as Thomas

à Becket, although some consider this incorrect. St Thomas Becket (December 21, 1118 - December

29, 1170) was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1162 to 1170. He

engaged in a conflict with King Henry II over the rights and

privileges of the Church and was assassinated by followers of the

king in Canterbury Cathedral. He is also commonly known as Thomas

à Becket, although some consider this incorrect.

Thomas Becket was born in London sometime between 1115 and 1120,

though most authorities agree that he was born December 21, 1118,

at Cheapside, to Gilbert of Thierceville, Normandy, and Rosea or

Matilda of Caen. His parents were of the upper-middle class near

Rouen, and Thomas never knew hardship as a child.

One of Thomas's father's rich friends, Richer de L'aigle, was

attracted to the sisters of Thomas. He often invited Thomas to

his estates in Sussex. There, Thomas learned to ride a horse,

hunt, behave, and engage in popular sports such as jousting. When

he was 10, Becket received an excellent education in "Civil

& Canon Law" at Merton Priory in England, and then

overseas at Paris, Bologna, and Auxerre. Richer was later a

signer at the Constitution of Clarendon against Thomas.

Upon returning to the Kingdom of England, he attracted the notice

of Theobald, Archbishop of Canterbury, who entrusted him with

several important missions to Rome and finally made him

archdeacon of Canterbury and provost of Beverley. He so

distinguished himself by his zeal and efficiency that Theobald

commended him to King Henry II when the important office of Lord

Chancellor was vacant.

Henry, like all the Norman kings, desired to be absolute ruler of

his dominions, both Church and State, and could find precedents

in the traditions of the throne when he planned to do away with

the special privileges of the English clergy, which he regarded

as fetters on his authority. As Chancellor, Becket enforced the

king's danegeld taxes, a traditional medieval land tax that was

exacted from all landowners, including churches and bishoprics.

This created both a hardship and a resentment of Becket among the

English Churchmen. To further implicate Becket as a secular man,

he became an accomplished and extravagant courtier and a cheerful

companion to the king's pleasures. Young Thomas was devoted to

his master's interests with such a firm and yet diplomatic

thoroughness that scarcely anyone, except perhaps John of

Salisbury, doubted his allegiance to English royalty.

King Henry even sent his son Henry, later the "Young

King", to live in Becket's household, it being the custom

then for noble children to be fostered out to other noble houses.

Later that would be one of the reasons his son would turn against

him, having formed an emotional attachment to Becket as a

foster-father. Henry the Young King was reported to have said

Becket showed him more fatherly love in a day than his father did

his entire life.

Archbishop Theobald died April 18, 1161, and the chapter learned

with some indignation that the king expected them to choose

Thomas his successor. That election took place in May, and Thomas

was consecrated on June 3, 1162, in accordance with the king's

wishes.

At once there took place before the eyes of the astonished king

and country an unexpected transformation in the character of the

new archbishop. Having previously been a merry, pleasure-loving

courtier, Becket became an ascetic prelate in simple monastic

garb, fully devoted to the cause of the hierarchy and prepared to

do his utmost to defend it. Most historians agree that Becket

begged the king not to appoint him archbishop, knowing that this

would occur, and even warning the king that he could not be loyal

to two masters. Henry could not believe that his closest friend

would forsake their friendship, and appointed him to the

archbishopric anyway -- something he came to regret the rest of

his life.

In the schism which at that time divided the Church, Becket sided

with Pope Alexander III, a man whose devotion to the same strict

hierarchical principles appealed to him, and from Alexander he

received the pallium at the Council of Tours.

On his

return to England, Becket proceeded at once to put into execution

the project he had formed for the liberation of the Church in

England from the very limitations which he had formerly helped to

enforce. His aim was twofold: the complete exemption of the

Church from all civil jurisdiction, with undivided control of the

clergy, freedom of appeal, etc., and the acquisition and security

of an independent fund of church property.

The king

was quick to perceive the inevitable outcome of the archbishop's

attitude and called a meeting of the clergy at Westminster

(October 1, 1163) at which he demanded that they renounce all

claim to exemption from civil jurisdiction and acknowledge the

equality of all subjects before the law. The others were inclined

to yield, but the archbishop stood firm. Henry was not ready for

an open breach and offered to be content with a more general

acknowledgment and recognition of the "customs of his

ancestors." Thomas was willing to agree to this, with the

significant reservation "saving the rights of the

Church." But this involved the whole question at issue, and

Henry left London in anger. The king

was quick to perceive the inevitable outcome of the archbishop's

attitude and called a meeting of the clergy at Westminster

(October 1, 1163) at which he demanded that they renounce all

claim to exemption from civil jurisdiction and acknowledge the

equality of all subjects before the law. The others were inclined

to yield, but the archbishop stood firm. Henry was not ready for

an open breach and offered to be content with a more general

acknowledgment and recognition of the "customs of his

ancestors." Thomas was willing to agree to this, with the

significant reservation "saving the rights of the

Church." But this involved the whole question at issue, and

Henry left London in anger.

Henry called another assembly at Clarendon for January 30, 1164,

at which he presented his demands in sixteen constitutions. What

he asked involved the abandonment of the clergy's independence

and of their direct connection with Rome; he employed all his

arts to induce their consent and was apparently successful with

all but the Primate.

Finally even Becket expressed his willingness to agree to the

constitutions, the Constitutions of Clarendon; but when it came

to the actual signature, he defiantly refused. This meant war

between the two powers. Henry endeavoured to rid himself of his

antagonist by judicial process and summoned him to appear before

a great council at Northampton on October 8, 1164, to answer

allegations of contempt of royal authority and malfeasance in the

Lord Chancellor's office.

Becket denied the right of the assembly to judge him, appealed to

the Pope, and, asserting that his life was too valuable to the

Church to be risked, went into voluntary exile on November 2,

1164 embarking in a fishing-boat which landed him in France. He

went to Sens, where Pope Alexander was, while envoys from the

king hastened to work against him, requesting that a legate

should be sent to England with Denary authority to settle the

dispute. Alexander declined, and when Becket arrived the next day

and gave him a full account of the proceedings, he was still more

confirmed in his aversion to the king.

Henry pursued the fugitive archbishop with a series of edicts,

aimed at all his friends and supporters as well as Becket

himself; but Louis VII of France received him with respect and

offered him protection. He spent nearly two years in the

Cistercian abbey of Pontigny, until Henry's threats against the

order obliged him to move to Sens again.

Becket regarded himself as in full

possession of all his prerogatives and desired to see his

position enforced by the weapons of excommunication and

interdict. But Alexander, though sympathizing with him in theory,

favoured a milder and more diplomatic way of reaching his ends.

Differences thus arose between pope and archbishop, which became

even more bitter when legates were sent in 1167 with authority to

act as arbitrators. Disregarding this limitation on his

jurisdiction, and steadfast in his principles, Thomas treated

with the legates at great length, still conditioning his

obedience to the king by the rights of his order. Becket regarded himself as in full

possession of all his prerogatives and desired to see his

position enforced by the weapons of excommunication and

interdict. But Alexander, though sympathizing with him in theory,

favoured a milder and more diplomatic way of reaching his ends.

Differences thus arose between pope and archbishop, which became

even more bitter when legates were sent in 1167 with authority to

act as arbitrators. Disregarding this limitation on his

jurisdiction, and steadfast in his principles, Thomas treated

with the legates at great length, still conditioning his

obedience to the king by the rights of his order.

His firmness seemed about to meet with its reward when at last

(1170) the pope was on the point of fulfilling his threats and

excommunicating the king, and Henry, alarmed by the prospect,

held out hopes of an agreement that would allow Thomas to return

to England and resume his place. But both parties were really

still holding to their former ground, and the desire for a

reconciliation was only apparent.

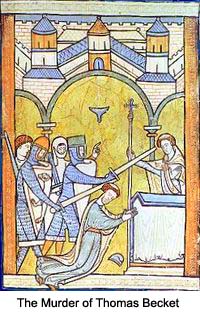

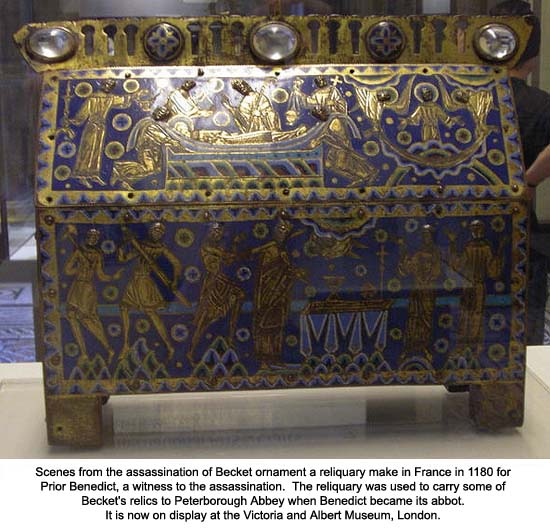

The tension between the two men would only be relieved by

catastrophe. Passionate words from the angry king (reputedly

"Will no one rid me of this meddlesome priest?",

"Who will rid me of this low-born priest?", "Who

will rid me of this turbulent priest?", or even "What a

band of loathsome vipers I have nursed in my bosom who will let

their lord be insulted by this low-born cleric!") were

interpreted as a royal command, and four knights -- Reginald

Fitzurse, Hugh de Moreville, William de Tracy, and Richard le

Breton -- set out to plot the murder of the archbishop. On

Tuesday, December 29, 1170, they carried out their plan,

murdering Thomas Becket at the entry of the Quire in Canterbury

Cathedral as he was leading the monastic community in

Vespers.

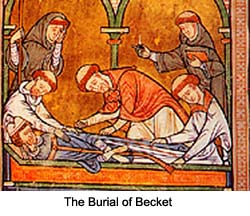

Most historians agree that Henry didn't actually intend for

Becket to be murdered, despite his harsh words. Following his

murder, it was discovered Becket wore a hairshirt under his

archbishop's garments. Soon after, the faithful throughout Europe

began venerating Becket as a martyr, and in 1173 -- barely three

years after his death -- he was canonized by Pope Alexander. On

July 12, 1174, in the midst of the Revolt of 1173-1174, Henry

humbled himself with public penance at Becket's tomb, which

became one of the most popular pilgrimage sites in England until

it was destroyed during the Dissolution of the Monasteries (1538

to 1541).

In 1220, Becket's remains were relocated from

this first tomb to a shrine in the recently completed Trinity

Chapel. The pavement where the shrine stood is today marked by a

lighted candle. Modern day archbishops celebrate the Eucharist at

this place to commemorate Becket's martyrdom and the translation

of his body from his first burial place to the new shrine.

Local legends in England connected with Becket arose after his

canonization. Though they are typical hagiographical stories,

they also display Becket's particular gruffness. Becket's Well,

in Otford, Kent, is said to have been created after Becket had

become displeased with the taste of the local water. Two springs

of clear water are said to have bubbled up after he struck the

ground with his crozier. The absence of nightingales in Otford is

also ascribed to Becket, who is said to have been so disturbed in

his devotions by the song of a nightingale that he commanded that

none should sing in the town ever again. In the town of Strood,

also in Kent, Becket is said to have caused that the inhabitants

of the town and their descendants be born with tails. The men of

Strood had sided with the king in his struggles against the

archbishop, and to demonstrate their support, had cut off the

tail of Becket's horse as he passed through the town.

Local legends in England connected with Becket arose after his

canonization. Though they are typical hagiographical stories,

they also display Becket's particular gruffness. Becket's Well,

in Otford, Kent, is said to have been created after Becket had

become displeased with the taste of the local water. Two springs

of clear water are said to have bubbled up after he struck the

ground with his crozier. The absence of nightingales in Otford is

also ascribed to Becket, who is said to have been so disturbed in

his devotions by the song of a nightingale that he commanded that

none should sing in the town ever again. In the town of Strood,

also in Kent, Becket is said to have caused that the inhabitants

of the town and their descendants be born with tails. The men of

Strood had sided with the king in his struggles against the

archbishop, and to demonstrate their support, had cut off the

tail of Becket's horse as he passed through the town.

St. Thomas of Canterbury remains the patron saint of Roman

Catholic secular clergy. In the Roman Catholic calendar of

saints, his annual feast day is 29 December.

Related Articles:

- Canterbury: Still the Perfect Pilgrimage!, by Julia Hickey

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/towns/canterbury.shtml

- Canterbury Cathedral, by John P. Seely

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/churches/canterbury.shtml

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Article and images reprinted from Wikipedia.org (stained glass photo courtesy of Britainonview.com).

|