On the Trail of Cornwall's "Free Traders"

by Grant Eustace

Daphne du Maurier used her beloved Cornwall as a backdrop for

several of her novels, and the sea, and particularly smuggling,

was at the heart of two of them. While they may have been

fiction, they were rooted in fact, and set in real places.

Frenchman's Creek is one of the inlets on the Helford

river, in the eastern side of the Lizard peninsula. The whole of

the Helford is peaceful and attractive, with picturesque villages

of ancient lineage on its banks: Manaccan, Gweek, and Helford

itself.

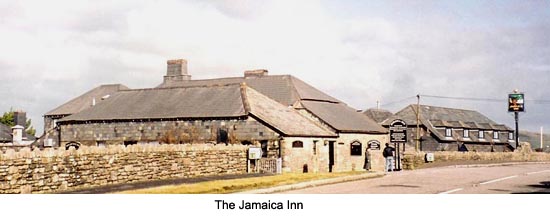

Jamaica Inn is still standing, and still functioning

with accommodation, bar and restaurant, at Bolventor on the main

A30 road as it crosses Bodmin Moor. It was built in the

mid-eighteenth century as a coaching inn, providing a haven for

travellers crossing what can still seem a forbidding stretch of

country. Daphne du Maurier herself stayed there in 1930, which

was what prompted the novel. Today there is also a collection of

smuggling artefacts at the Inn.

Each book title highlights one of the key aspects of successful

smuggling. Secluded locations, where Revenue officers patrol

only sporadically, if at all, are ideal for putting cargoes

ashore. And temporary storage, again out of choice in isolated

places, is required to hide the contraband from prying eyes until

it can be divided up and distributed. Typical of these, apart

from Jamaica Inn itself, is a farm close to a creek on the Fal

river, which was known as "a good depot, where landed kegs were

carried up a sunken road, and hidden in caves or in the

woods."

The smuggling of illegal goods -- drugs, immigrants, endangered

species -- is a relatively recent phenomenon. In the past, it

was usually the excise duties demanded by a greedy government,

even on everyday commodities like salt (as well as luxury items

such as silk clothing) which made it worthwhile for smuggler and

purchaser alike to run the risks of evading them. So it was in

the main period of Cornwall's smuggling, which was between

approximately 1700 and 1850. Its peak was in the second half of

the 18th century.

In 1783, for instance, a Government committee reported that there

were "considerable" vessels (meaning of some three hundred tons)

able to make "seven or eight voyages a yearΙ the largest of them

can bring, in one freight, the enormous quantity of three

thousand half-ankers of spirits, and ten or twelve tons of tea."

(The half-anker was a container holding four and a half gallons.)

Tobacco was another favourite commodity -- as the traditional

poem has it: "brandy for the parson, baccy for the clerk." It was

said in 1784 that for every ounce of tobacco sold legally, one

pound was smuggled.

Nor were those officials commenting on anything out of the

ordinary. Some eighteen years earlier, a legitimate tradesman

had noted that his employees encountered "sixty horses having

each three bags of tea on them of 56 or 58 pounds weight... landed

on a beach two miles to the west of Padstow." (Padstow, on the

north coast of Cornwall, is a bustling small port now best known

for its fashionable and much-frequented fish restaurants.)

The mention of beaches highlights the virtually insuperable

problem that faced those trying to enforce the law. Small

tree-lined creeks, like those along the rivers of the south coast

of Cornwall, were difficult enough to police -- and they were

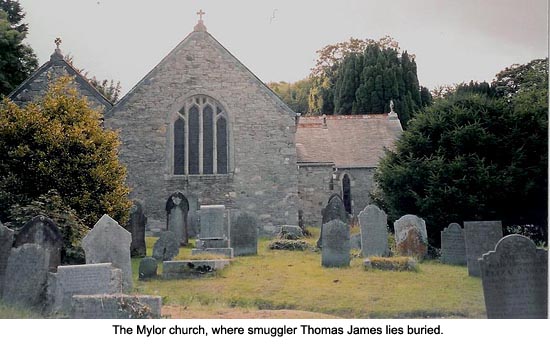

certainly used extensively for smuggling. Places such as Mylor

Creek, for example, which feeds into Falmouth's great natural

harbour of Carrick Roads. Mylor is still reached only by boat or

by a succession of descending narrow lanes off the A39, but is

worth the detour. The graveyard of its ancient church contains

the grave of one Thomas James, a smuggler shot by Customs

officers, as well as the largest Celtic cross found in Cornwall.

(Don't be misled by the mere ten feet that are visible -- there

are another seven in the ground.)

But the nub of the problem for the authorities was the long,

sparsely-inhabited Cornish coastline and its many coves. While

they had a justifiably fearsome reputation at high tide in a

gale, since there were innumerable rocks that even now will rip

steel hulls to shreds, at calm low water many of them have broad,

gently shelving stretches of sand that were ideal for bringing

small boats ashore to meet the waiting strings of ponies. Some

beaches, indeed, were employed that way for above-board commerce.

Trebarwith Strand, on the north coast between Tintagel and Port

Isaac, for example, was used in the 19th century to load slate

from the nearby quarries.

> >

Visitors can go to all of these places simply for their

breathtaking beauty, and on the north coast to surf as well. But

many of them, such as the dramatic pair Kynance and Mullion on

the Lizard peninsula, were associated with smuggling, and one or

two achieved particular notoriety. Prussia Cove, situated where

the Lizard in the north-west turns into the broad sweep of

Mount's Bay, was one. This description of it could suit a hundred

others: "a spot so sheltered and secluded that it is impossible

to see what boats are in the little harbour until one literally

leans over the edge of the cliff above".

From 1770 to 1807, the extraordinary Carter brothers -- of whom

one, John, adopted the title of King of Prussia, although he

often demurred to his sibling Captain Harry -- operated primarily

from Prussia Cove. Although their combining a real trade of

fishing with smuggling clearly put them well outside the law,

they were devout Methodists who allowed no swearing among their

crew. When one of their cargoes was seized, they 'released' it

again by raiding the Penzance Customs House. But they took only

their own cargo, leaving undisturbed the contraband that

'belonged' to others.

So daring did many smugglers become that they sometimes

ignored that requirement for an isolated place in which to land

their cargoes. Most of the coastal harbours that, again,

tourists visit now because of their attractiveness had active

smugglers among their inhabitants: Polperro, St Mawes, Fowey and

Mevagissey on the south coast, Boscastle, Newquay and Hayle on

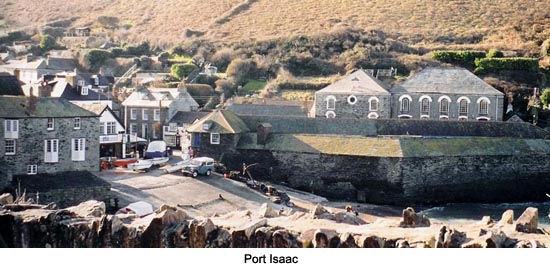

the north. Port Isaac, also on the north coast, and a port long

before the pier was built in the 16th century, has an association

with another smuggler -- but one more legend than fact,

delighting in the name of Cruel Copinger.

Nor were smugglers always as careful as they might have been when

it came to storing their contraband, often simply choosing the

public houses in which they did their regular drinking. The

'Bush' in Morwenstowe, the 'Dolphin' in Penzance, the 'Ship' in

Porth Leven and 'The Jolly Sailor' in Looe are among those where

a present-day visitor might stop for a drink and not necessarily

realise the strong associations with smugglers. In the last of

these, indeed, the landlady is supposed to have sat upon a keg of

contraband brandy while Revenue officers searched in vain.

This can make smuggling sound like a game -- especially when you

read of other stories, such as an incident in 1831. A Revenue

cutter followed a 'hot lead' and arrested a boat which they

brought into Bude (on the north Cornish coast), only to find it

was full of nothing but salt herring. But there were times when

it became deadly serious. In 1827, for example, a fairly brazen

run of contraband into the area of Falmouth harbour was

intercepted and the cargo seized. The 'free traders,' reportedly

some thirty strong, retaliated and took back their 'possessions,'

with shots exchanged and one Customs officer beaten unconscious

and left for dead.

Yet despite the mutual antagonism, humanity could still take

precedence over ancient feuds. On a freezing December night in

1805, two Excise officers were travelling on the south-western

edge of that same Bodmin Moor where Jamaica Inn is situated. They

got hopelessly lost, and eventually stopped exhausted. They

would have died of exposure if two local tin miners had not

happened across them, and brought them to safety.

Then, as now, Cornish hospitality won out.

Related Articles:

- Parsons, Scarecrows and Fear: Kent's Smuggling Heritage, by Richard Crowborough

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/country/smuggling.shtml

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Grant Eustace is a professional writer active in a

variety of fields, from film and video through print to radio

and on-line content, the last two of these principally for the

BBC World Service. He also works with -- and speaks regularly at

international gatherings of -- the Tourism and Cultural Identity

Committee of the World Trade Centers Association.

Article and photos © 2006 Grant Eustace

Coast photo courtesy of Britainonview.com

|