Carlisle and the Border Reivers

by Julia Hickey

Welcome to the

16th century and the frontier between England and Scotland. This

is a lawless land; rustling, murder and lynching are everyday

occurrences. This is a place where a man's safety depends upon

his prowess in arms and the power of his extended family -- not

to mention the thickness and height of his walls! For this is the

lawless realm that introduced the words 'bereave' and 'blackmail'

to the English language. In these harsh times the feuding

inhabitants -- Grahams, Armstrongs, Nixons, Maxwells and

Musgraves -- owe allegiance to no one but themselves. A traveller

falling into the clutches of an armed gang pleaded with them for

mercy. "Are ye no Christians?" he begged. Welcome to the

16th century and the frontier between England and Scotland. This

is a lawless land; rustling, murder and lynching are everyday

occurrences. This is a place where a man's safety depends upon

his prowess in arms and the power of his extended family -- not

to mention the thickness and height of his walls! For this is the

lawless realm that introduced the words 'bereave' and 'blackmail'

to the English language. In these harsh times the feuding

inhabitants -- Grahams, Armstrongs, Nixons, Maxwells and

Musgraves -- owe allegiance to no one but themselves. A traveller

falling into the clutches of an armed gang pleaded with them for

mercy. "Are ye no Christians?" he begged.

The response came, "No, we're Elliotts."

Today Cumbrians will give you a warm and friendly welcome, but

the landscapes, often stark but always stunning, resonate with

the history of a turbulent past.

Where better to begin than the administrative centre of the

Western Marches? Visit the Carlisle tourist information office in

the market place. It is situated in the predominantly

18th-century Old Town Hall, but the oldest parts of the building

survive from Queen Elizabeth's reign. Maps, books and leaflets

containing everything from opening times to walks and cycle rides

and the history of the region can be found here. Pause to admire

the market cross from where Bonnie Prince Charlie declared

himself to be king of England before visiting Tullie House, now

Carlisle's award-winning museum.

Here, a permanent exhibition, including a dramatic film show that

runs for approximately ten minutes, sets the scene for the brutal

but compelling history of the reivers who roamed the borders

between England and Scotland for more than 300 years. Reiving was

not only the passtime of outlaws and bullies; respectable men

reived their Scottish neighbours' sheep and cattle. Theft and

countertheft were so engrained in the border way of life that

rules for Truce Days and regulations for pursuing reivers were

devised to ensure some sort of established authority and code of

conduct. If a man's cattle were stolen a crown officer could

call for a "hot trod:" a sod of burning peat was hoisted on a

spear and the wronged party could travel unhindered into the

neighbouring country in search of his belongings. In theory,

law-abiding people were supposed to provide assistance to men

riding in pursuit of stolen goods, but in practice this was often

not the case.

This systematic lawlessness and violence grew from the border

wars that raged between England and Scotland during the medieval

period, when the borderers suffered the consequences of invasion

and counter-invasion. Carlisle Castle itself changed hands

between the English and the Scots on several occasions during

this period. By the time of Henry VIII, border warfare was

sporadic and Carlisle was firmly under English control. Still,

the danger of invasion, looting and pillaging remained constant

-- though more seasonal than during the years of open warfare --

because for the borderers it had become a way of life.

Living with the constant threat of violence bred a very

aggressive race of people. If they weren't fighting the Scots

they were arguing amongst themselves. They were very proud and

took offence easily, so that before many centuries had passed

whole families were at feud with one another over some ancient

vendetta. It is even said that borderers traditionally excluded

the sword hand of any male child to be christened so that in time

of raiding and blood feud he would be all the stronger in his

fighting for not having to worry too much about damnation!

The principal reivers gained a reputation for villainy

because they didn't abide by the rules and robbed from both the

Scots and the English side of the border. Many of their deeds

were handed down in legend and song before being immortalised by

Sir Walter Scott. Find out at Tullie House if you're descended

from border bandits; inspect steel bonnets, short swords and

double headed axes; hear the sad tale of Isabel Routledge left

widowed by a reiver raid. The coffee and cake served in the

cafeteria are pretty good too.

Then take a short journey through the millennium subway that

links Tullie House with the imposing red sandstone castle. The

black granite pavement is inscribed with a roll-call of riding or

raiding surnames and at the entrance stands the "Bishop's" stone

-- a huge speckled boulder testifying to one man's anger at the

reivers' misdeeds. By 1524 the church was determined to act to

stop the reivers' ungodly ways. Cardinal Wolsey described the

marches as an "evil country," but the Bishop of Glasgow was

rather more specific. The stone carries part of the extensive

curse that he had read from pulpits in neighbouring Tynedale when

he excommunicated every single reiver in the land. Unfortunately

for law abiding citizens (and there don't seem to have been many)

it doesn't seem to have had a great deal of impact on the broken

men in the Debateable Lands (patches of disputed territory that

acted as a buffer zone between England and Scotland) or the

career criminals who lived in the region. The Debateable Lands

were ideal for men who might have reason to fear the law. In

addition to being isolated and often mountainous, neither kingdom

would recognise the authority of the other in these disputed

regions. This allowed the "broken men" who lived there to play

one warden off against another with little fear of

retribution.

Broken men were reivers

who had been formally outlawed by either the Scottish or English

authorities. For example, if someone -- let's call him Jack --

was involved in a murder, the chief of Jack's family might be

asked to stand bail for him. If the head of the family refused,

then Jack would be "put to the horn." This meant that he was

declared an outlaw in the nearest convenient market square and in

theory if he was caught he could be hung. By refusing to stand

bail for Jack, the clan chief had denied that Jack belonged to

his family. In practice, of course, no one took a great deal of

notice of their broken status. One family of Armstrongs was

notable because they were all broken men! Broken men were reivers

who had been formally outlawed by either the Scottish or English

authorities. For example, if someone -- let's call him Jack --

was involved in a murder, the chief of Jack's family might be

asked to stand bail for him. If the head of the family refused,

then Jack would be "put to the horn." This meant that he was

declared an outlaw in the nearest convenient market square and in

theory if he was caught he could be hung. By refusing to stand

bail for Jack, the clan chief had denied that Jack belonged to

his family. In practice, of course, no one took a great deal of

notice of their broken status. One family of Armstrongs was

notable because they were all broken men!

As you come up out of the subway, the castle awaits. It has

stood guard over Carlisle for more than 300 years. Henry VIII,

recognizing the role of gunnery in warfare, added the half-moon

battery inside the outer courtyard. During the 16th century it

was occupied by the Warden of the Western Marches. It also

played host to Mary Queen of Scots and in 1596 to a rather less

illustrious Scotsman -- Kinmont Willie Armstrong, a notorious

headsman of an equally notorious border family.

Armstrong was arrested on a truce day when all the inhabitants of

the region could meet for markets, games and justice. He was

taken to Carlisle Castle by English officers of the crown where

the warden, Lord Scrope, threw him into prison. This was

contrary to border law. The Laird of Buccleuch, the Keeper of

Liddesdale -- a Scottish officer -- roused his forces and

together with Willie's family rode for Carlisle. They crossed

the River Eden with scaling ladders, intending to go over the top

of the castle walls. This plan went awry when the ladders

collapsed. Undeterred, the resourceful Scots kicked open the

postern gate, discovered Armstrong -- bound by chains that

rattled loudly -- and escaped back over the storm swollen river

waters. The story continues:

We scarce had won the staneshaw-bank,

When a' the Carlisle bells were rung,

And a thousand men, in horse and foot,

Cam wi' the keen Lord Scrope along

Scrope and his thousand men didn't recapture Willie

Armstrong. The crows at Harraby gallows were deprived of their

meal. No doubt Scrope, who had to explain the escape to

Elizabeth, wished that he had incarcerated Armstrong in the dark

dungeons beneath the keep where the only moisture to be had was

from the notorious "licking stone." The dungeons are open to the

public and retain a damp cold feel -- not the kind of place you'd

want to be on your own in the middle of the night. Scrope and his thousand men didn't recapture Willie

Armstrong. The crows at Harraby gallows were deprived of their

meal. No doubt Scrope, who had to explain the escape to

Elizabeth, wished that he had incarcerated Armstrong in the dark

dungeons beneath the keep where the only moisture to be had was

from the notorious "licking stone." The dungeons are open to the

public and retain a damp cold feel -- not the kind of place you'd

want to be on your own in the middle of the night.

Follow Armstrong and Buccleuch north, out of Carlisle towards

junction 44 of the M6. Scotland Road boasts a 10-foot-tall

reiver clad in steel bonnet and leather jack, gazing out towards

the hills. Follow the A689 to Brampton and continue to

Lanercost. You are at the very edge of the Debateable Lands,

where neither England nor Scotland ruled.

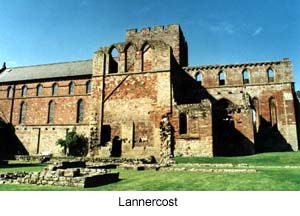

Lanercost Priory, now a ruin, was abandoned in 1535 during the

Dissolution of the Monasteries. The priory is small but

beautiful. An informative audio-tour takes visitors around the

walls, undercofts and rooms. The tour can be paused and visitors

can take time to explore on their own or sit on a bench enjoying

the sun and the sound of birdsong. This is a place that feels a

million miles from the 21st century. But in the 16th century it

wasn't so much a backwater as a frontline. So it isn't surprising

that the site should contain two pele towers.

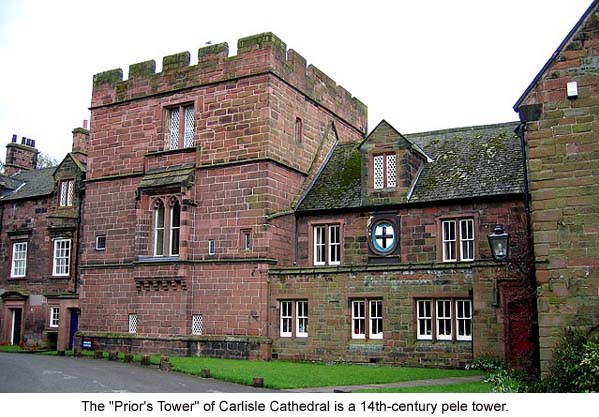

There are more than 100 pele towers and bastle houses in Cumbria.

A pele tower is a stoutly built tower, rather like a medieval

keep -- and indeed many of them date from the 13th century when

wars between England and Scotland raged. The wealthy lived in

pele towers; other borderers equipped themselves with bastle

houses. A bastle house is a basic tower with a store room at the

bottom. This could be used for livestock or it could be packed

with peat, which was then set alight, deterring reivers who were

thus denied easy access to the first and second floors of the

house. Bastle houses were used as refuges rather than permanent

living quarters. When beacon lights filled the skies, families

would gather their valuables and lock themselves in these

buildings and hope that the reivers would bypass their homes and

livestock. Pele towers and bastle houses are unique to the

British Isles.

The rest of the population, living in huts with thatched roofs,

could either find shelter with a rich relation or rely on the

thickness of their church walls for sanctuary. The fortified

church at Great Salkeld in the Eden Valley is an excellent

example, with walls six feet thick, a sturdy tower and a large

room beneath the ground floor where frightened woman and children

could hide until the danger passed.

Following the Union of England with Scotland, James I (James VI

in Scotland) ordered that these fortified buildings be demolished

in an attempt to pacify the region. The majority of surviving

towers became part of the fabric of working farms, like the one

at Askerton on the way to Bewcastle. Others were converted into

more comfortable stately homes. Two examples can be found near

Penrith: Hutton-in-the-Forest and Dalemain. Both are open to the

public. The pele tower at Dalemain lies at the heart of the

existing building. The cafeteria is situated in the medieval

hall. It is also home to a fine collection of doll's houses and

a delightful house for mice built into one of the wooden stairs.

Take a walk along the footpath from Dalemain to Dacre for a

glimpse of yet another tower. Dacre isn't open to the public and

the path can be muddy at times but the church is worth a visit

and the pub serves hearty meals.

If you want to visit an unaltered pele tower, there are several

fine examples beyond the Western Marches. The best example in

England is called Aydon Castle, near Hexham. Built in the 13th

century, it still retains its barmkin -- an enclosed courtyard

for livestock. Two others, Smailholm and Hermitage -- home of

infamous border baron Bothwell -- are in Scotland.

Follow the winding lanes deep into the hills beyond Lanercost for

a visit to Bewcastle. This isolated village is home to a Roman

fort, a castle and the Bewcastle Cross. It was also the home of

Hobbie (short for Halbert) Noble, who features in one of Scott's

border ballads: "his misdeeds they were sae great, they banished

him to Liddesdale."

Today, there is no sign of Hobbie, but a quick inspection of the

churchyard reveals many reiving names: Armstrong, Storey, Bell

and of course Noble. The East Cumbria Country Side Project

offers two walks from Bewcastle. The leaflet is called "Bastles

in the West March." It can be purchased from Carlisle Tourist

Information Office.

Head back towards Hadrian's Wall and Hexham. On the way there you

might want to stop at Housesteads, the most complete Roman fort

in Britain. Nearby are the remains of a bastle and farmhouse

owned by generations of Armstrongs who also claimed Housesteads

as theirs. The last Armstrong to own the fort -- which made an

ideal centre for his horse stealing operation -- was hung at the

beginning of the 18th century. His brothers fled to America, no

doubt to avoid a similar end.

Hexham, "the capital of Tynedale," is in the English

Middle March. This little town is built around the impressive

Saxon abbey. It also contains the first purpose-built prison in

England. Built in 1330 to contain convicted reivers, it is now

the home of the Border History Museum. Having reopened in 2005

after extensive renovations, it is well worth a visit. An

audio-visual tour leads visitors through the gaol, which depicts

tragic and terrible tales. Experience a reiver raid; listen to

the tragedy of the English lassie who loved a bonnie Scot's lad;

and relive the tale of the scabby sheep. A newly installed glass

lift carries visitors down to the dungeons for a glimpse of the

convicted reivers' quarters, and if there's time (and a volunteer

available), you can browse through some of the ballads and

stories stored in the Hexham Moothall Border Library collection

now rehoused in the old goal. Hexham, "the capital of Tynedale," is in the English

Middle March. This little town is built around the impressive

Saxon abbey. It also contains the first purpose-built prison in

England. Built in 1330 to contain convicted reivers, it is now

the home of the Border History Museum. Having reopened in 2005

after extensive renovations, it is well worth a visit. An

audio-visual tour leads visitors through the gaol, which depicts

tragic and terrible tales. Experience a reiver raid; listen to

the tragedy of the English lassie who loved a bonnie Scot's lad;

and relive the tale of the scabby sheep. A newly installed glass

lift carries visitors down to the dungeons for a glimpse of the

convicted reivers' quarters, and if there's time (and a volunteer

available), you can browse through some of the ballads and

stories stored in the Hexham Moothall Border Library collection

now rehoused in the old goal.

In addition to discovering the border reivers by car and by foot

it is also possible to take to two wheels. Follow all or part of

the 175-mile Reivers Cycle Route. Whichever mode of transport you

choose, you'll be fascinated by the life and times of the likes

of Kinmont Willie, Bold Buccleuch, Jock o'the Side, Dick o'the

Cow, Johnie Armstrong and Belted Will.

Related Articles:

- Lancaster, by Elizabeth Ashworth

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/towns/lancaster.shtml

More Information:

Books:

These resources are invaluable if your appetite for border

history has been whetted.

Durham, Keith. (1995). The Border Reivers. (Osprey

Publishing.) A good introduction to the reivers and some

dramatic colour plates including one depicting the rescue of

Kinmont Willie from Carlisle Castle.

MacDonald Fraser, George. (1971). The Steel Bonnets.

(HarperCollins.) This is the definitive book offering a

detailed history of the reivers and their unsavoury habits

Moss, Tom: Deadlock and Deliverance. The capture and rescue of Kinmont Willie Armstrong, the most notorious Scottish Reiver of the 16th century, was the last great event in the reivers' history.

It would prove to be the last time the Reivers, adhering to a society which put allegiance to the clan first and foremost, would clash with both Scottish and English authority and monarchy on a scale which would shake both nations. http://www.reivershistory.co.uk

Ordnance Survey: In Search of the Border Reivers.

A useful map for pinpointing reiver haunts in Cumbria,

Northumbria and Scotland. It also provides a timeline and a list

of reiver family names.

Reed, James (ed). (1991). Border Ballads -- A

Selection. (Carcanet Press.) In addition to a selection

of the most dramatic ballads from a variety of sources, Reed

provides a short history of the period and commentary to

accompany the ballads.

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Julia Hickey is passionate about England's heritage and particularly of Cumbria, where her husband comes from. In between dragging her family around the country to a variety of historic monuments, she works part-time as a senior lecturer at Sheffield Hallam University. She spends the rest of her week writing. In her spare time, she enjoys walking, dabbling in family history, cross-stitch, tapestry and photography.

Article and photos © 2006 Julia Hickey

Pele tower photo courtesy of Visitcumbria.com

|