The Lingering Power of Fountains Abbey

by Julia Hickey

Even on the most overcast day, Fountains Abbey has the power to provoke a mood of contemplation and awe, as if centuries of prayer and monastic life have been soaked into the mortar that holds the great stone blocks together. The story of the Abbey, nestling in the Yorkshire Dales, tells the tale of the rise and fall of monasticism in England.

Even on the most overcast day, Fountains Abbey has the power to provoke a mood of contemplation and awe, as if centuries of prayer and monastic life have been soaked into the mortar that holds the great stone blocks together. The story of the Abbey, nestling in the Yorkshire Dales, tells the tale of the rise and fall of monasticism in England.

Monastic life played a central role in religious life and society in Medieval England. Evidence suggests that there may have been as many as 600 monastic buildings in England alone, but in 1066 there were only 30, all following the Benedictine rule. St Benedict of Nursia first wrote his rules for monastic communities in the 6th century. These were reformed and declared to be the rule for English monasteries in the 10th century. However, by the 12th century, many monasteries had drifted away from a life of religious simplicity into a lifestyle more associated with wealth than poverty. Benedictine monasteries were often elaborate in design and the men who lived behind their walls dined well and lived like lords. Many abbots wore furs and kept hounds.

In 1132, thirteen Benedictines -- so-called "black monks" on account of their clothing -- sought to return to the life of simplicity that was closer to the Rule of St. Benedict than the current way of life in the abbeys of England. Leaving their former abbeys, they travelled into the wild landscape of the Yorkshire hills. There they found a small, sheltered valley with a fresh supply of water and hills that would yield the materials they needed to build a new abbey.

The thirteen monks in the wilds of Yorkshire were not alone in their desire for reform and a life of simplicity. The Cistercian order of monks had been founded in 1098 in Burgundy; the order -- with its commitment to austerity -- arrived in England in 1128. By 1135 the new monastery at Fountains had also become part of the Cistercian brotherhood. The ruins that visitors see today reflect the simplicity of Cistercian beliefs. The monks wanted a building that was functional and unadorned by elaborate or ornate decorations. They wanted to concentrate on their life of prayer rather than being distracted by trappings of worldly wealth. Thus, the walls of Fountains Abbey are solidly built, the mouldings around the windows and doors stark and simple in their inspiration. The grandeur that visitors see in Fountains comes from the solid clean lines of soaring walls and the majesty of the skyward curving arches.

The location of Fountains was also ideal for the contemplative life. Even now, amidst the bustle of modern life and the jostle of tourists, it is possible to find a moment of solitude to enjoy the tranquillity that Fountains Abbey exudes. Sheltered on either side by woodland and deer park, the skies around the abbey are filled by the sound of birdsong, and on a summer day it is impossible not to be enchanted by the sparkling River Skell as it passes beneath the infirmary and refectory.

Not Just Woolgathering...

The Cistercians' desire for discipline, firm monastic rule and simplicity of life was best symbolised by their rough, undyed sheeps-wool habits -- hence their nickname of "the white monks." Visitors to Fountains during the cold winter months should remember that the monks who lived here were not allowed to wear furs or warm underclothes -- just their habits.

The White Monks were so determined that their monastic lives should not become corrupted or worldly in any way that they refused to rely on gifts and patronage for their survival. Other monasteries received gifts of money and lands in return for their prayers, but the Cistercians decided that they would support themselves. Ironically, their desire for financial independence from the secular community led to Fountains Abbey being the richest monastic community in the kingdom by the middle of the 12th century.

The White Monks were so determined that their monastic lives should not become corrupted or worldly in any way that they refused to rely on gifts and patronage for their survival. Other monasteries received gifts of money and lands in return for their prayers, but the Cistercians decided that they would support themselves. Ironically, their desire for financial independence from the secular community led to Fountains Abbey being the richest monastic community in the kingdom by the middle of the 12th century.

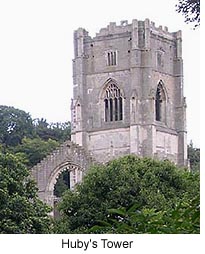

A window in Huby's Tower that lies closest to the present footpath recognises the source of the wealth that allowed the successive abbots to continue expanding the abbey complex, and for Abbot Huby to build the huge Perpendicular tower that dominates the site. Two sheep, heavy with wool, support the base of the arches that form the window. The grandeur and scale of Fountains is due to the monk's business acumen. In addition to clothing and feeding them (although meat was permitted only to the monks or lay brothers who worked in the fields) the wool of the sheep farmed on hilly wastelands around the abbey found its way across England and onto the markets of Europe. The coffers of the Cistercians were quickly filled -- although in later years poor investment resulted in the monks owing large sums of money to many people. The monks also diversified into horse breeding, lead mining and quarrying. These last two were logical developments, given the building work that the monks themselves carried out.

Another reason for the size of Fountains lies in the fact that the monks wished to spend their lives in prayful contemplation, rather than looking after the sheep that provided the wool for their habits and the funds for their buildings. Thus the Cistercians employed "lay brothers" who lived within the Abbey complex but separate from the choir monks, who spent their days in prayer and song. These lay brothers were required to take lesser vows and were allowed a better diet. They had their own sleeping, eating and infirmary quarters within the abbey precincts.

A Never-ending Building Programme

As the power of the monks at Fountains grew, the abbey received more and more wealthy visitors, who granted the abbey sizable parcels of land. The abbey's guest's lodge was built to house them. During this period of prosperity the monks naturally added buildings to the abbey, including the impressively named "Chapel of the Nine Altars". The only other chapel of this type in England can be found at Durham and Fountains is the blueprint.

Despite the building programme that continued throughout the abbey's lifetime the monks remained true to the principles of simplicity that the Burgundians and original monks had aspired to. The nave is enormous, the buttresses and columns substantial, but they are solidly crafted rather than ornate. The only ornament of the kind associated with most cathedrals and abbeys of the Norman or Gothic period is in the Chapel of the Nine Altars. At the top of one of the arched windows an angel can be found holding a shield. Visitors finding the matching location on the external walls can see a strange pagan-looking creature -- almost as if the world outside the monastery is heathen and wild whilst the prayer and songs of the monks brings heaven much closer to earth inside. The grotesque outside the walls and the angel inside were not part of the original plans, however. The stonework was only inserted when a crack appeared in the masonry in the late 15th century.

Despite the building programme that continued throughout the abbey's lifetime the monks remained true to the principles of simplicity that the Burgundians and original monks had aspired to. The nave is enormous, the buttresses and columns substantial, but they are solidly crafted rather than ornate. The only ornament of the kind associated with most cathedrals and abbeys of the Norman or Gothic period is in the Chapel of the Nine Altars. At the top of one of the arched windows an angel can be found holding a shield. Visitors finding the matching location on the external walls can see a strange pagan-looking creature -- almost as if the world outside the monastery is heathen and wild whilst the prayer and songs of the monks brings heaven much closer to earth inside. The grotesque outside the walls and the angel inside were not part of the original plans, however. The stonework was only inserted when a crack appeared in the masonry in the late 15th century.

The remains of the great east window are typical of the abbey. It is magnificent not because of its decoration but because its size and simplicity fosters a sense of space. The ribbed vaulting sprouts like so many great tulips from the sturdy columns of the cellarium (the storehouse found in the west range of the complex); light filters through narrow windows; zigzag mouldings round arched doorways; the day-stairs are worn by time and the soft pacing of monks going about their offices.

With such a large population, the monks also had to concern themselves with health and hygiene. In addition to the two infirmaries -- one of which must have been amongst the largest in England -- the abbey boasts an impressive drainage system. The River Skell, today flowing through the ruins into a series of artificial lakes built in the 18th century by John Aislabie, was redirected from its natural course to flow beneath the latrine area, carrying away monastic debris.

Plague, Rebellion -- and Bad Management

Times changed, however. The early success of the Cistercians at Fountains was followed by a period of economic upheaval that altered the way the abbey functioned. During the 14th century, the abbey was burned down during a Scottish raid, and also fell victim to bad harvests and bad financial mismanagement. The Black Death killed off the lay brothers that the White Monks relied upon for their manual labour. It also contributed to the decline of the feudal system that kept peasants tied to the land. The monks could no longer find men willing to give up family life to be lay brothers and were forced to become landlords instead, letting their land to tenant farmers.

Even so, it was after this period of decline that one of the greatest Cistercian abbots was appointed to Fountains. Marmaduke Huby, who had been a monk for 30 years before his election to abbot, sat in Parliament and drove new building projects. Under his rule, the number of monks living at Fountains rose once again. When he died in 1526, he probably felt that he had breathed new life into the great abbey. The 52 monks who lived under his rule could not have known that his death was the beginning of the end of Fountains.

Even so, it was after this period of decline that one of the greatest Cistercian abbots was appointed to Fountains. Marmaduke Huby, who had been a monk for 30 years before his election to abbot, sat in Parliament and drove new building projects. Under his rule, the number of monks living at Fountains rose once again. When he died in 1526, he probably felt that he had breathed new life into the great abbey. The 52 monks who lived under his rule could not have known that his death was the beginning of the end of Fountains.

Huby's successor, William Thirsk, was not as wise as Huby, nor as virtuous. He is said to have sold land, timber and jewels belonging to the abbey for his own use. Admittedly, however, this accusation is biased, as it relies entirely on the evidence supplied by Thomas Cromwell's agents during the Visitation of the Monasteries in 1536. Cromwelll, Henry VIII's chief minister, had begun to take account of the riches that the monks had secreted behind their monastery walls, and to look for ways to relieve them of it. Cromwell's protestant zeal and his practical desire to please the king were united behind the cause of showing the monks to be corrupt and superstitious. Thirsk was forced to resign as abbot and went to live at the nearby abbey of Jervaulx.

Instead of living quietly on the pension that he had been provided with, however, Thirsk became involved with the Pilgrimage of Grace. This was a revolt led by Northern Catholics in 1536, who sought to force Henry VIII to return to the Catholic Church, reopen the abbeys and get rid of Protestant reformers. Henry VIII, however, was not to be stopped. Thirsk and the Abbot of Jervaulx were sent to the Tower of London, where they were both found guilty of treason and suffered traitors' deaths -- hanging, drawing and quartering.

Although the monks at Fountains were innocent of complicity in the revolt, the days of the monasteries were numbered. In 1539, all the monasteries of England were suppressed, their lands and buildings sold and their contents stripped away. The greatest Cistercian abbey in the kingdom was chopped up and dispersed. Today the abbey still tells a mute tale of its butchery. The great nave is roofless, its lead sold to the highest bidder. There are holes through the masonry where lead piping once ran; sockets and corbels where timbers once rested; empty spaces once filled by glass that was transported to Ripon and York. The abbey doors can be seen in a nearby mill (the only example of a Cistercian corn mill in the country), where they were used as flooring. The Elizabethan house nearby -- Fountains Hall -- was built with stones torn from the abbey walls.

Rising from the Ruins

Despite the devastation it suffered during the dissolution of the monasteries, Fountains remains one of the most complete monastic complexes in the country -- possibly because of its remote location and also because of the River. John Aislabie, MP for nearby Ripon, purchased the ruined abbey and the land surrounding it in 1720. He and his son set about creating a water garden, incorporating the ruins into Studley Royal's classically inspired temples and vistas. The River was dammed and channeled into a canal and a series of lakes where Aislabie, his family and his friends could walk and be at one with nature. Eagle-eyed visitors may notice that some of the herbs grown by the monk remain: The edge of the river is lined with comfrey, or knit-bone as it is also known.

Today, visitors can still enjoy the tranquillity once sought by the monks and Aislabie, as they explore the ruins, walk by the River Skell or explore the deer park that surrounds the abbey. There is no other abbey quite like Fountains. Time stops from the moment Huby's tower appears on the skyline and draws visitors down into the valley. At the end of the day, after enjoying one of the National Trust's excellent meals, a leisurely picnic, or an ice-cream so indulgent that you can almost hear ghostly monks tut-tutting, visitors go away feeling relaxed and refreshed -- and knowing that one visit to Fountains is not enough.

There is always something new to discover in the grounds and amongst the extensive ruins of this World Heritage Site. Different qualities of light reveal new facets of the buildings. Floodlit and filled with the sound of hymns, the abbey seems to slip back into a time before the abbeys were dissolved and the monks dispersed.

Don't miss out on its magic!

Fountains Abbey Photo Gallery

By Moira Allen

Studley Royal

Related Articles:

- Where Emperors, Kings and Saints Have Walked: York Minster, by Julia Hickey

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/churches/minster.shtml

- Four Great Abbeys and Priories of Yorkshire, by Dawn Copeman

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/churches/abbeys.shtml

- Hidden Churches of Yorkshire, by Louise Simmons

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/churches/yorkshire.shtml

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Julia Hickey is passionate about England's heritage and particularly of Cumbria, where her husband comes from. In between dragging her family around the country to a variety of historic monuments, she works part-time as a senior lecturer at Sheffield Hallam University. She spends the rest of her week writing. In her spare time, she enjoys walking, dabbling in family history, cross-stitch, tapestry and photography.

Article © 2005 Julia Hickey

Photos © 2005 Adam Hewgill

Abbey Model photo and Photo Gallery © 2003 Moira Allen

|