The Hidden Treasures of Chester Cathedral

by Julia Hickey

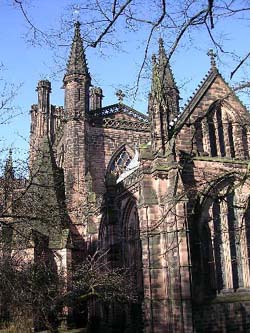

From a distance, the cathedral church of Christ and the Blessed Mary seems to lack the grandeur and awe of some of the larger churches containing a Bishop's seat or "cathedra". The church of the bishops of Chester is a compact red sandstone building that looks more Victorian than medieval. From a distance, the cathedral church of Christ and the Blessed Mary seems to lack the grandeur and awe of some of the larger churches containing a Bishop's seat or "cathedra". The church of the bishops of Chester is a compact red sandstone building that looks more Victorian than medieval.

Yet as a visitor draws closer, the cathedral's treasures begin to reveal themselves. A frieze of flowers, grotesque faces, impossible monsters and startled birds run around the building at eye level in hues ranging from deep red to a subtle pink. Look higher to discover coiled lizards, grimacing figures, haughty lords and ladies, and angels peering down from the masonry. These carvings spring from the bases of window arches, hide in sheltered corners and under copings, or perch on cornices. The small size of the cathedral makes these delightful creatures easy to view. The cathedral also boasts a fine crop of gargoyles -- a gurgling, stiff-necked species that funnel water from the roof and away from the walls.

The greeting at Chester is warm and a guidePORT audiotour helps unravel some of the cathedral's story. The one thing visitors shouldn't do is keep their eyes at one level, or they'll miss corbels, intricate bosses and carvings created by some long-dead mason. And Chester Cathedral isn't a mausoleum: craftspeople are still offering their creativity to the glory of God here. The windows in the south-nave aisle were created to mark the ninth centenary of the cathedral and are a riot of colour.

The story of Chester Cathedral begins, somewhat unusually, with the Vikings. These bold, bad warriors sailed their dragon-prowed boats up the River Dee to Chester's shores. The people of old Deva were terrified and turned to the church for protection as the Vikings began to settle in the Wirral. Chester's defence came in the form of the relics of St Werburgh. Werburgh, the daughter of a Saxon king, was supposed to have many healing powers. She is often portrayed with a goose that she is said to have returned to life after it had not only died but been cooked and eaten! After her death she was buried in Staffordshire at a monastic house that she founded, but in the 10th century her relics were moved to Chester. Her shrine can still be seen, though it is badly battered by Tudor iconoclasts who wished to rid England of Popish influences at the time of the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The stone shrine was broken up and the saint's bones dispersed around the cathedral, while the saints that once adorned the niches were smashed to pieces.

Long before Henry's thugs got to work, however, the Saxon Minster began to grow. Hugh Lupus, a relation of William the Conqueror, was granted Chester in recognition of his services to the Norman king. He decided that Chester Minster should be transformed into a Benedictine Abbey. He sought the help of Anselm and his Norman monks, and before many years had passed, black-cowled figures moved quietly between stoutly carved pillars and sat in the draughty cloisters working with vellum and goose quills to produce beautifully written manuscripts. One of these can still be seen in the chapter house. Long before Henry's thugs got to work, however, the Saxon Minster began to grow. Hugh Lupus, a relation of William the Conqueror, was granted Chester in recognition of his services to the Norman king. He decided that Chester Minster should be transformed into a Benedictine Abbey. He sought the help of Anselm and his Norman monks, and before many years had passed, black-cowled figures moved quietly between stoutly carved pillars and sat in the draughty cloisters working with vellum and goose quills to produce beautifully written manuscripts. One of these can still be seen in the chapter house.

Since then the cathedral has undergone many transformations. The nave is lighter and larger now and the tower is much higher. But the monastic imprint remains. Visitors looking up to the windows west of the screen may spot the Chester imp -- a devil bound by chains. The quire originally built by Edward I's architect may be much altered, but the wooden quire stalls date from the 13th century. The stalls are a treasure-house of Baltic oak carved into misericords, canopies and benches. The ends of the benches are all worked into different figures, and close inspection of the richly waxed surfaces reveal faces, hounds, biblical representations, angels, dragons and an elephant carrying a castle. The craftsman who created this piece obviously listened to descriptions of the exotic beast and then blended it with the largest creature he could imagine -- for the Chester elephant rejoices in horse's legs and hooves! Even the floor tiles of the quire are filled with faces. and don't forget the gilded angels on the ceiling encouraging the choristers with their own heavenly chorus. Time slips by here. The more you look. the more you find.

The original quire building was constructed during the 13th century by Richard of Chester. Richard was Edward I's engineer and more used to military projects. King Henry III, Edward's father, took the earldom of Chester into his keeping when first Ranulf and then John -- previous earls of Chester -- died. Edward, at that time Prince, was made Earl of Chester in 1254 (a title still retained by the eldest son of England's monarch). Edward was keen to ensure that Chester remained in good defensive order because it lay on the borders between Wales and England and was often plagued by warfare between the two nations. This perhaps helps explain Chester Cathedral's stout walls and businesslike proportions. The original quire building was constructed during the 13th century by Richard of Chester. Richard was Edward I's engineer and more used to military projects. King Henry III, Edward's father, took the earldom of Chester into his keeping when first Ranulf and then John -- previous earls of Chester -- died. Edward, at that time Prince, was made Earl of Chester in 1254 (a title still retained by the eldest son of England's monarch). Edward was keen to ensure that Chester remained in good defensive order because it lay on the borders between Wales and England and was often plagued by warfare between the two nations. This perhaps helps explain Chester Cathedral's stout walls and businesslike proportions.

The Lady Chapel can be found behind the Quire, along with the chapel dedicated to St Werburgh. Today the Lady Chapel has been restored to something approaching the brightness that medieval monks might recognise, a color lost for many centuries. The abbey was dissolved in 1541 by Henry VIII; when the shrine to St Werburgh was broken, the bright colors that decorated the walls were also whitewashed.

The King, anxious that no martyrs should be encouraged during this time of religious, social and political upheaval gave instructions that the cult of Thomas a Becket should be dismantled wherever it was found. Consequently there are very few original ornaments containing any references to the troublesome bishop in the larger and more influential churches of this country. Yet in the Lady Chapel of Chester Cathedral, if visitors look up they will see a richly decorated boss showing Thomas being murdered for daring to defy his king. Clearly Henry VIII's men were so busy destroying masonry and decoration at ground level that they failed to look up.

Chester Abbey escaped the fate that lay in wait for so many of England's monasteries because of its remoteness: until that time the area had been administered by a distant bishopric. Henry concluded that Chester needed its own bishop. So the abbey was returned to the townspeople of Chester in a relatively undamaged state as their cathedral. Thomas Clark, the last abbot, was the first dean. The story of the dissolution and the role of King Henry is told in the glass of the Chapter House windows. Today the evidence of the cathedral's monastic past can be seen most readily in the cloisters and cloister gardens, as well as in the form of the wooden altar in St Werburgh's chapel. Chester Abbey escaped the fate that lay in wait for so many of England's monasteries because of its remoteness: until that time the area had been administered by a distant bishopric. Henry concluded that Chester needed its own bishop. So the abbey was returned to the townspeople of Chester in a relatively undamaged state as their cathedral. Thomas Clark, the last abbot, was the first dean. The story of the dissolution and the role of King Henry is told in the glass of the Chapter House windows. Today the evidence of the cathedral's monastic past can be seen most readily in the cloisters and cloister gardens, as well as in the form of the wooden altar in St Werburgh's chapel.

Having escaped serious damage during the Tudor period, the cathedral was to suffer more damage at the hands of Cromwell's Puritans the following century. Anything within hammer's reach was defaced. Even the memorial to John Green, a Tudor mayor (to be found at the crossing of the Cathedral) was damaged. John and his two wives are without hands because their attitude of prayer smacked of popishness. Miraculously, the quire survived unscathed and St Werburgh's shrine lay unnoticed thanks to the fact that it had been scattered around the cathedral by Henry's assault.

During 19th century restoration works, various parts of Werburgh's shrine were relocated and in 1888 reassembled in the Lady Chapel. Very few examples of this type of shrine remain as the majority were more thoroughly destroyed by England's reformers. The wooden figure representing Werburgh was placed there in 1993.

The cathedral underwent a major rebuilding programme in the 19thn century. Not only did it grow, it became much lighter as more windows were added in the nave. The north aisle also saw the return of colour in the form of delightful mosaic panels retelling Bible stories. Ancient and modern were blended together. In the baptistery, for example, the arches were heightened and the peacock font added. Yet the lamp that hangs above it dates from the 17th century and a board for nine men's morris scratched in one of the stones supporting the pillars was etched by a bored monk many centuries previously. The cathedral underwent a major rebuilding programme in the 19thn century. Not only did it grow, it became much lighter as more windows were added in the nave. The north aisle also saw the return of colour in the form of delightful mosaic panels retelling Bible stories. Ancient and modern were blended together. In the baptistery, for example, the arches were heightened and the peacock font added. Yet the lamp that hangs above it dates from the 17th century and a board for nine men's morris scratched in one of the stones supporting the pillars was etched by a bored monk many centuries previously.

The cathedral also contains the only complete example of an ecclesiastical court dating from the 17th century; an unusual cobweb picture; and a memorial to the sailors aboard HMS Chester, who died during the Battle of Jutland in 1916. Poignantly, a number of the sailors are recorded as boys, including a 16-year-old who received a posthumous Victoria Cross.

After browsing among Chester Cathedral's treasures and perhaps finding a few minutes for silent contemplation, it is time to go to the refectory for a cup of fair trade tea and a Danish pastry. The refectory was built in the 13th century for the monks. Today's visitors are not required to enforce the rule of silence! A relaxing half hour can be spent chatting in the warmth of the sun that pours through the many windows, illuminating the graffiti that has been etched into the walls by distant visitors and long-gone school boys. One name, dated 1669, is particularly striking. The modern Creation window sends its colours spinning downwards from one end of the refectory while at the other end of the room saints and kings tell their tale. It is impossible to miss the unusual stone canopied pulpit with its stone steps built into the wall where a monk once read chapters from the Bible.

Then it's out into the tiny cathedral precinct with its cobbled surface and Georgian houses before passing beneath an arch and away from the peace of Chester Cathedral back into the bustle of Chester's shoppers.

Related Articles:

- Chester, by Sue Wilkes

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/towns/chester.shtml

- Timeline: Chester, by Darcy Lewis

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/towns/chestime.shtml

- Hidden Churches of Cheshire, by Louise Simmons

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/churches/cheshire.shtml

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Julia Hickey is passionate about England's heritage and particularly of Cumbria, where her husband comes from. In between dragging her family around the country to a variety of historic monuments, she works part-time as a senior lecturer at Sheffield Hallam University. She spends the rest of her week writing. In her spare time, she enjoys walking, dabbling in family history, cross-stitch, tapestry and photography.

Article © 2005 Julia Hickey

Photos © 2005 Adam Hewgill

|