Who Is Father Christmas?

by Dawn Copeman

Many

people today think that Father Christmas is just the British name

for Santa Claus. Whilst it is true that Father Christmas and

Santa are considered virtually the same today, Father Christmas

is a completely different person entirely, with a much longer

history. Many

people today think that Father Christmas is just the British name

for Santa Claus. Whilst it is true that Father Christmas and

Santa are considered virtually the same today, Father Christmas

is a completely different person entirely, with a much longer

history.

The American Santa Claus has one source. He originated from

Dutch settlers' stories about Sinter Klass, the Dutch name for St

Nicholas, and how he gave presents to girls and boys.

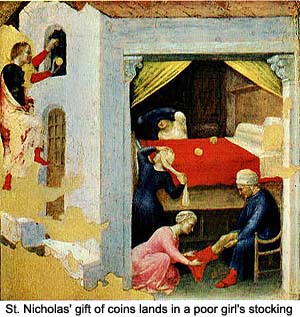

St Nicholas was Bishop of Myra, in Turkey in the 3rd century AD,

who would travel in his red bishop's robes and give gifts to the

poor. He was believed to have been particularly kind to

children. Apparently, he was also very shy. Legend has it that

one day, wanting to give money to a family in secret, he dropped

some gold coins down the chimney, where they landed in a girl's

stocking. St. Nicholas didn't 'arrive' in Britain until after

the Norman invasion, and when he did arrive his story was quickly

absorbed into the legend of Father Christmas. By this time, our

Father Christmas had already been around for centuries!

The earliest Father Christmas appeared during ancient British

mid-winter festivals. He wasn't known as Father Christmas then,

of course, but as a general pagan figure who represented the

coming of spring. He would wear a long, green hooded cloak and a

wreath of holly, ivy or mistletoe. It is the association with

holly and mistletoe, and his ability to lift people's spirits,

that we retain from this ancient Father Christmas.

When Britain fell

under Saxon rule in the fifth and sixth centuries AD, Father

Christmas took on the characteristics of the Saxon Father Time,

also known as King Frost or King Winter. Someone would dress up

as King Winter and be welcomed into homes, where he would sit

near the fire and be given something to eat and drink -- a bit

like our mince pies and whisky for Father Christmas, perhaps? It

was thought that by being kind to King Winter, the people would

get something good in return: a milder winter. Thus Father

Christmas became associated with receiving good things. When Britain fell

under Saxon rule in the fifth and sixth centuries AD, Father

Christmas took on the characteristics of the Saxon Father Time,

also known as King Frost or King Winter. Someone would dress up

as King Winter and be welcomed into homes, where he would sit

near the fire and be given something to eat and drink -- a bit

like our mince pies and whisky for Father Christmas, perhaps? It

was thought that by being kind to King Winter, the people would

get something good in return: a milder winter. Thus Father

Christmas became associated with receiving good things.

This association was strengthened when the Vikings invaded

Britain and brought their own midwinter traditions with them.

The 20th through the 31st of December is known as Jultid -- the

time when the Norse God Odin takes on the character of Jul, one

of his twelve characters, and visits the earth. The name lives on

today as Yuletide. During Jultid Odin, a portly, elderly man with

a white beard and a long, blue, hooded cloak was said to have

ridden through the world on his eight-legged horse Sleipnir,

giving gifts to the good and punishments to the bad. Our Father

Christmas became fat like Odin and developed the ability to

automatically know whether people had been bad or good. Also like

Odin, Father Christmas could travel magically and be in lots of

places in a short space of time.

Then with the arrival of the Normans and the story of St Nicholas

the creation of the British Father Christmas was complete. Our

first written reference to the entity of Father Christmas is

found in a 15th century carol, which includes the line "Welcome,

my lord Christëmas." From this point onwards, Father

Christmas is seen to represent the spirit of Christmas: that of

good cheer and benevolence to all. In Tudor and Stuart times Sir

Christmas or Captain Christmas was called upon to preside over

the Christmas entertainment in large houses. In 1638, we got our

first image of Father Christmas courtesy of Thomas Nabbes, who

illustrated him as an old man in a furred coat and cap.

But this reverence of a pagan figure

and revelry was too much for the Puritans, and so in 1644 they

banned Christmas and Father Christmas as well. Father Christmas

then went underground and took a greater role in Mummers Plays,

often striding onto the stage at the beginning of the play to say

"In comes I, old Father Christmas, be I welcome or be I not? I

hope old Father Christmas, will never be forgot." He also

appeared in underground newspapers under the name of Old

Christmas, where he was used as a representation of what people

felt about Christmas and what they missed about it. But this reverence of a pagan figure

and revelry was too much for the Puritans, and so in 1644 they

banned Christmas and Father Christmas as well. Father Christmas

then went underground and took a greater role in Mummers Plays,

often striding onto the stage at the beginning of the play to say

"In comes I, old Father Christmas, be I welcome or be I not? I

hope old Father Christmas, will never be forgot." He also

appeared in underground newspapers under the name of Old

Christmas, where he was used as a representation of what people

felt about Christmas and what they missed about it.

Yet it was not until the Victorian age that Father Christmas was

truly revived as the spirit of Christmas. The Victorian Father

Christmas embodied elements of all his predecessors and was

usually drawn as a jolly, pagan figure in a long, hooded coat --

the colour of which could be red, blue, green or brown. The

Ghost of Christmas Present in A Christmas Carol as

illustrated by John Leech, is very pagan indeed; with his green

cloak and holly wreath he is a direct link to the most ancient

Christmas Spirit of all.

By the middle of the 20th century, our Father Christmas had

changed again. This time he was heavily influenced by America --

by Clement C. Moore's 1822 poem "The Night before Christmas", by

the illustrations it inspired Thomas Nash to draw for Harper's

Weekly, and by the Coca Cola Company. In Moore's

poem we see a St Nick who combines all the characteristics of

Odin, St Nicholas and our Father Christmas. From Nash's drawings,

which were heavily influenced by Moore's poem, we got the idea

that Santa lives at the North Pole, has a list of good and bad

children and reads letters from children -- letters which in

Britain were posted up the chimney! And although Father

Christmas had worn red before, to represent St Nicolas' Bishop's

Robes, it was the Coca Cola Company's advert of 1931 that helped

to make red the standard colour for Father Christmas's coat.

Thus Santa and Father Christmas became one. But although they

are similar today, Father Christmas is not Santa; he is much,

much more than that.

In this medley of Victorian cards, the robes of Santa or Father Christmas range

from blue and turquoise to purple and green, sometimes trimmed with fur or flecked

with stars. In most cases, Santa has not developed the "bowl full of jelly"

belly that Clement Moore ascribed to him.

|

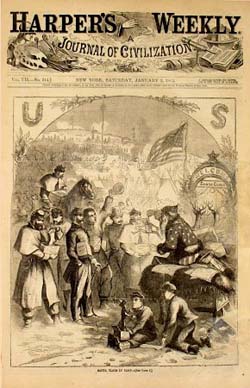

In Harper's Weekly in 1863, Santa Claus (whose robe seems

to be covered with stars) gives gifts to Union troops.

|

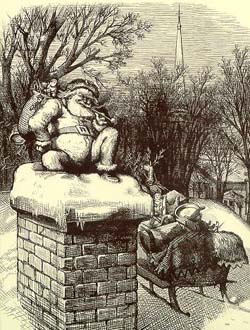

By 1874 in Harper's Weekly, Santa's

costume seems to becoming closer to what we're familiar with

today.

|

Dawn Copeman is a freelance writer and commercial writer who has had more than 100 articles published on travel, history, cookery, health and writing. She currently lives in Lincolnshire, where she is

working on her first fiction book. She started her career as a freelance

writer in 2004 and has been a contributing editor for several publications, including TimeTravel-Britain.com and Writing-World.com .

Article © 2005 Dawn Copeman

|