A Victorian Christmas

by Pearl Harris

On

December 18, 1988, Britain's Sunday Telegraph proclaimed Charles

Dickens as "the man who invented Christmas." And it is surely

true that no other writer has left the world with a clearer

picture of Christmas in Victorian England than Dickens. On

December 18, 1988, Britain's Sunday Telegraph proclaimed Charles

Dickens as "the man who invented Christmas." And it is surely

true that no other writer has left the world with a clearer

picture of Christmas in Victorian England than Dickens.

Dickens might not have invented Christmas, but he is

credited with the great revival of Christmas traditions in the

Victorian era, which have continued in one form or the other to

the present day in all English-speaking countries around the

globe.

Dickens was born in 1812 in Portsmouth, and his childhood was far

from easy, coming as he did from a large family with rather

unconventional parents. From his mother, Elizabeth, he inherited

a keen sense of the ridiculous. The disastrous financial

affairs of John, his father, resulted in the young Charles being

put to work at the age of 12 and the entire family, except for

Charles and one sister, being incarcerated in a Debtors Prison.

For someone whose formal education ended at such a tender age,

the eternal magic and genius of his prose seem nothing short of

the miraculous.

Out of his five Christmas Books, A Christmas Carol

(published on 17 December, 1843) is surely one of his best-loved

works. The uplifting tale of the heartless miser Ebenezer

Scrooge and his reform at Christmas time have been immortalized

in countless film and theatrical productions.

Just as A Christmas Carol profoundly influenced Victorian

readers, its simple message of love, goodness and charity

continues to touch modern readers in the same way. However, A

Christmas Carol is not only an uplifting moral tale, but one

of great historical importance due to Dickens' brilliant, witty

and detailed description of a Victorian Christmas.

From its pages we are able to soak in the atmosphere of a cold,

frosty Christmas Eve. Workers scurry home with the eager

anticipation of a rare day off work. Shopkeepers close up their

shutters. Fires are lit in hearths throughout the country.

Families, both poor and wealthy, gather around the Christmas tree

("That pretty German toy", as it is referred to by Dickens).

The Christmas Tree tradition began in the

Victorian era, with the custom of a lighted evergreen

(Tannenbaum) originating in Germany. German-born Prince

Albert, Consort of Queen Victoria, brought the idea to England

and by the mid-19th century, Christmas Trees at Windsor Castle

were decorated with wax candles and laden with presents. As

citizens copying the Royal tradition spread this custom, the

Christmas Tree soon became a popular English tradition. The Christmas Tree tradition began in the

Victorian era, with the custom of a lighted evergreen

(Tannenbaum) originating in Germany. German-born Prince

Albert, Consort of Queen Victoria, brought the idea to England

and by the mid-19th century, Christmas Trees at Windsor Castle

were decorated with wax candles and laden with presents. As

citizens copying the Royal tradition spread this custom, the

Christmas Tree soon became a popular English tradition.

It was (and still is) considered bad luck to remove the Christmas

Tree and other Christmas decorations before Twelfth Night (6th

January). Superstition stated that it was also bad luck to put

up a Christmas Tree before Christmas Eve, although other

Christmas decorations might appear some time before

Christmas. The mistletoe, holly and ivy were considered

magical plants because of their winter berries. Mistletoe, with

its pagan origin, was not allowed inside churches. The English

custom of kissing under the mistletoe had the restriction that

there could only be as many kisses as berries. Every time a

couple kissed beneath the mistletoe, a berry was to be removed

from the sprig. Holly was used as a decoration and also

to decorate the Christmas Pudding. The red "male" berry was

meant to protect the household from witchcraft and could only be

brought into the home by a male. The "female" ivy, with its

leaves that remained green throughout the winter, was a symbol of

immortality. Some time before Christmas, Christmas cards

were mailed. The first Christmas card was designed in 1846 by J.

Calcott Horsley for Sir Henry Cole, Chairman of the Society of

the Arts. In that first year, a mere 1000 cards were printed.

By 1870, with postage reduced to one penny per ounce and cheaper

color lithography having been introduced, the popularity of

sending friends and family members Christmas cards rapidly

increased. The most common designs of Victorian Christmas cards

were plum puddings and church bells.

Prince Albert imported many other German Christmas

traditions besides the tree. As he was particularly partial to

rich pudding, the flamed Christmas Pudding was given Royal pride

of place at Christmas, beside German cookie-cutter cookies and

gingerbread. Prince Albert imported many other German Christmas

traditions besides the tree. As he was particularly partial to

rich pudding, the flamed Christmas Pudding was given Royal pride

of place at Christmas, beside German cookie-cutter cookies and

gingerbread.

Dickens describes the streets of London

with its shops gaily decorated with sprigs of Holly and Christmas

Day as being the one day off work in the year. On Christmas Eve,

Scrooge grumbles to his clerk as he reluctantly gives him the

following day off: "A poor excuse for picking a man's pocket

every twenty-fifth of December! But I suppose you must have the

whole day. Be here all the earlier next morning".

The

Victorian custom of carol-singing on Christmas Eve and Christmas

Day is also given life by Dickens thus: Scrooge was too miserly

to open his door to any carolers, so one young caroler "stooped

down by Scrooge's keyhole to regale him with a Christmas Carol.."

and was given short shrift! Carols were also sung at home, with

some families going from door to door singing. The wassailers

were usually the poor, who offered others a drink from their

wooden bowls and expected donations of food, drink or money in

return.

We soak in the wintry atmosphere of Christmas Eve as Dickens

writes of the bitter cold, frost and fog in the streets of London

in contrast to the cozy fires burning in the hearths of most

homes as families gather together to celebrate Christmas.

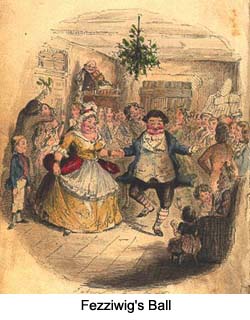

In many Victorian firms, it was customary for employers to

entertain employees and apprentices on Christmas Eve. Dickens

vividly describes one such "Domestic Ball" in a warehouse: "lamps

were trimmed, fuel was heaped upon the fire; and the warehouse

was as snug, and warm, and dry, and bright a ball-room as you

would desire to see upon a winter's night." The employees are

entertained by a fiddler, they dance, eat cake, cold roast and

mince pies and drink beer and negus" (hot, spicy mulled

wine). In many Victorian firms, it was customary for employers to

entertain employees and apprentices on Christmas Eve. Dickens

vividly describes one such "Domestic Ball" in a warehouse: "lamps

were trimmed, fuel was heaped upon the fire; and the warehouse

was as snug, and warm, and dry, and bright a ball-room as you

would desire to see upon a winter's night." The employees are

entertained by a fiddler, they dance, eat cake, cold roast and

mince pies and drink beer and negus" (hot, spicy mulled

wine).

In addition to negus, common drinks at Christmas were various

kinds of Gin Punch, including Purl (heated beer, flavored with

gin, sugar and ginger) and Bishop (a Punch made with heated red

wine, flavored with oranges, sugar and spices).

The Victorian Christmas was a merry, joyous, family celebration

with "the brightness of the roaring fires in kitchens, parlors,

and all sorts of rooms". Again, in Dickens's unique prose: "Here,

the flickering of the blaze showed preparations for a cozy

dinner, with hot plates baking through and through before the

fire, and deep, red curtains, ready to be drawn to shut out cold

and darkness. There, all the children of the house were running

out into the snow to meet their married sisters, brothers,

cousins, uncles, aunts, and be the first to greet them."

Christmas Day was celebrated with Mass, heralded by the peal of

Church bells. "But soon the steeples called good people all to

church and chapel, and away they came, flocking through the

streets in their best clothes, and with their gayest faces". The

traditional Christmas Church service consisted of carol-singing

and scripture readings.

Christmas Dinner was a

sumptuous occasion. Turkey was not traditionally served in

England until the late 19th century. Instead goose, chicken or

roast beef took pride of place on the Christmas table, followed

by Christmas Pudding made from beef, raisins and prunes. Christmas Dinner was a

sumptuous occasion. Turkey was not traditionally served in

England until the late 19th century. Instead goose, chicken or

roast beef took pride of place on the Christmas table, followed

by Christmas Pudding made from beef, raisins and prunes.

Mince Pies -- made with mincemeat and spices -- were also

traditional Christmas fare and were eaten for the 12 days of

Christmas, ensuring good luck for the next 12 months of the year.

According to custom, each of the twelve mince pies had to be

baked by someone different.

Even in humbler households, Christmas Dinner was a very special

occasion, with a goose, apple sauce and mashed potatoes followed

by Christmas Pudding being enjoyed by the poor Cratchit family.

It was common for the poor family without proper cooking

facilities to carry their Christmas dinners to the baker's shops

to be cooked at Christmas. Dickens mentions this custom: "And at

the same time there emerged, from scores of by-streets, lanes,

and nameless turnings, innumerable people carrying their dinners

to the bakers' shops".

The Sunday before Advent, known as Stir-up Sunday, was the day to

mix the Christmas Pudding so that it could be well matured by

Christmas Day. Each family member had to take it in turns to

stir the Pudding with a wooden spoon (to honor the wooden crib of

the Christ Child). Stirring was to be done clockwise to ensure

good luck! As Mrs. Cratchit proudly carries in the Christmas

Pudding, the importance of this once-a-year treat is highlighted

by Dickens:

"A great deal of steam! The pudding was out of the copper. A

smell like a washing-day! That was the cloth. A smell like an

eating-house and a pastry cook's next door to each other, with a

laundress's next door to that! That was the pudding! In half a

minute Mrs. Cratchit entered -- flushed, but smiling proudly --

with the pudding, like a speckled cannon-ball, so hard and firm,

blazing in half of half-a-quartern of ignited brandy, and bedight

with Christmas holly stuck into the top. O, a wonderful

pudding!"

After Christmas dinner, the poor Cratchit family settles down

around their hearth, enjoying together some fruit, hot negus and

chestnuts roasted on the fire. In more prosperous families,

Christmas dinner usually ended with gift-giving and pulling of

Christmas Crackers (an invention in 1847 by the Londoner Tom

Smith). The day would be rounded off with music, carol-singing

and parlor games such as Forfeits and Blind Man's Buff.

At Christmas, it would be most appropriate for us all to heed the

immortal wisdom of Charles Dickens as penned in the 1850

Christmas issue of Household Words:

"And I do come home at Christmas. We all do, or we all

should. We all come home, or ought to come home, for a short

holiday -- the longer, the better -- from the great

boarding-school, where we are for ever working at our

arithmetical slates, to take, and give a rest. As to going a

visiting, where can we not go, if we will, where have we not

been, when we would, starting our fancy from our Christmas Tree!"

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Pearl Harris, whose ancestors hail from Britain, was born in South Africa, where she lived for most of her life until emigrating to the Czech Republic in 2002 with her husband, their dog and cat. She is now a teacher of English as a second language and freelance travel writer. Pearl has travelled extensively in Africa, Europe, the USA and Britain. Recently she undertook a car journey through England and Northern Ireland, visiting major sites of historical interest. Her main interests are travel, photography, reading and writing. Besides a qualification as a Diagnostic Radiographer, Pearl has a B.A. in English and Linguistics and post-graduate Diploma in Translation.

Article © 2005 Pearl Harris

Plum Pudding photo courtesy of BritainOnView.com

|