Old Sarum: A Layer-Cake of History

by Moira Allen

If you're looking for a site that typifies the multi-layered

nature of British history, look no farther than Old Sarum.

Situated just north of the city of Salisbury and west of Castle

Road (A345), the mound known today as Old Sarum has been the site

of a Neolithic settlement, an Iron Age Hillfort, a Roman military

station, and a Norman palace and cathedral, before fading into

history on a final sour note as a "rotten borough."

In Roman times, the hill was known as Sorvioduni or

Sorbiodoni. It is referred to as Searobyrg in the

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, and Sarisberie in the Domesday

Book. The name "Sarum," which begins to appear in the early 13th

century, seems actually to be the result of a sort of medieval

typo. In medieval manuscripts, the name "Sarisberia" or

"Sarisburia" was often abbreviated as simply "Sa" -- but a mark

at the end of this abbreviation (and others like it) was often

incorrectly taken for an "r" and believed to indicate the suffix

"rum." In the case of Sarum, the typo stuck, causing the site to

be known both as Sarum and Salisbury.

At first glance, Sarum may seem an unlikely (or at least

unpleasant) location for a settlement, let alone a royal castle.

A 13th-century poem by Henry d'Avranches describes it as "a

windy, rainswept place without flowers or birds... the bare chalk

dazzled the eyes... There was a shortage of water, and a tiring

climb to the top of the hill." The Victoria County History of

Wiltshire, however, expands upon this grim picture to explain

its appeal:

Yet it had one supreme advantage. In time of war, and

rumour of war, its quality as a fortress was unrivalled in the

neighborhood. It commanded the whole area; none could approach

without being observed; it was protected on three sides by steep

banks; and it dominated the River Avon and the Roman roads. Yet it had one supreme advantage. In time of war, and

rumour of war, its quality as a fortress was unrivalled in the

neighborhood. It commanded the whole area; none could approach

without being observed; it was protected on three sides by steep

banks; and it dominated the River Avon and the Roman roads.

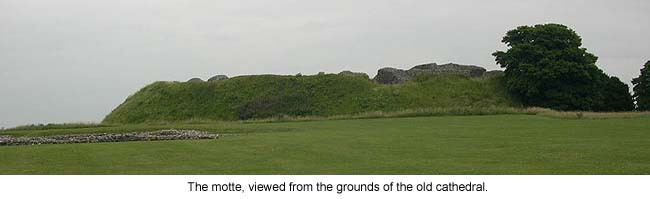

Today, the bareness of chalk no longer dazzles the eye; instead,

all is covered with a deceptively lush carpet of grass. But the

wind and rain can still be troublesome, so when visiting Old

Sarum (even in summer!), dress warmlyĐand prepare yourself for

some truly spectacular scenery, for the hilltop does indeed

command an unparalleled view of the surrounding countryside in

every direction.

As a visitor, you enter Old Sarum through an opening in the

earthworks that surround the Iron Age hillfort and now,

prosaically, guard the car-park. From there you'll proceed to

the Norman motte that rises from the center of its ditch. A

wooden bridge leads up to the location of the former gatehouse,

where you'll pay your entrance ticket and be enticed to pick up

a souvenir or two in the shop. (It must be said that the

pickings are fairly slim.) From there, you wander amidst the

ruins of gray stone walls and across the grassy sward that covers

an array of interesting-looking, but largely unexcavated, lumps

and outcroppings.

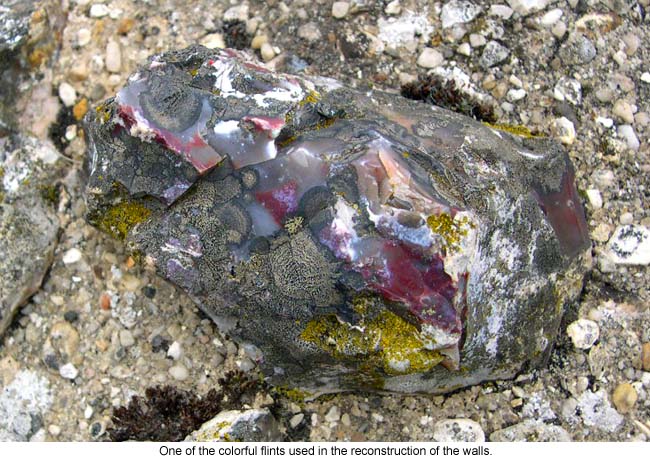

If it strikes you that the stones in these ruined walls seem just

a bit too regular, you'd be right: The "ruins" are an illusion.

They aren't actually the remains of Old Sarum's Norman keep;

they're modern reconstructions, based upon the locations of the

castle's foundations. They're still worthy of closer inspection,

however, for embedded within this gray, dreary rubble are chunks

of flint that display an amazing array of colors.

The first occupants of the site were Stone Age hunters, who

left stone tools that can be seen in the Salisbury museum. These

were followed by farmers, whose field systems eventually extended

across the plains and who, as they moved into the Iron Age,

constructed the original hill-fort on the site. The Romans

followed, but left few traces on Old Sarum; the site seems to

have been more of a way-station than a fort. After the Romans

left, it appears that the Britons returned to their hillfort,

only to be driven out once and for all by Cynric, king of the

West Saxons, in 552. The site then remained abandoned until

around 900 AD, when it was given to the Saxon bishopric of

Sherborne. In the late 900s, when the Saxons were facing the

threat of Viking invasions, the hillfort's banks and ditches were

strengthened. This seems to have been effective, for when Sweyn

the Danish Viking sacked and burned the town of Wilton in 1003,

he apparently made no attempt to attack nearby "Sarisburia."

The first Norman castle upon the site was built of

timber and constructed at some time before 1070, for it was

already present when William the Conqueror chose this location to

pay off his troops and disband his army. Old Sarum was not simply

another Norman fortress, however; it was a royal castle, the

property ("juris proprium") of the king. In 1086,

according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, all landowners "of any

account" throughout England were required to come to Salisbury to

pay homage to William, who held additional councils here in 1088

and 1096. The first Norman castle upon the site was built of

timber and constructed at some time before 1070, for it was

already present when William the Conqueror chose this location to

pay off his troops and disband his army. Old Sarum was not simply

another Norman fortress, however; it was a royal castle, the

property ("juris proprium") of the king. In 1086,

according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, all landowners "of any

account" throughout England were required to come to Salisbury to

pay homage to William, who held additional councils here in 1088

and 1096.

It wasn't until the reign of Henry I, however, that the keep

itself was built in 1100. Henry then handed over the building

project to Roger, Bishop of Salisbury, who was apparently a great

builder of castles (and who owned several). It was Roger who

oversaw the construction of a new stone palace between 1130 and

1139. But Roger's real masterpiece was the construction of a new

cathedral below the castle, constructed on the site of an earlier

cathedral built by Bishop Osmund between 1075 and 1092. This

first cathedral lost its tower to a storm only five days after it

was consecrated (did I mention it was windy?). Rather than

repairing the building, Roger erected a replacement that was

twice the size of the original, and that stood taller than the

castle on the hill above it! Modeled on churches in Rome, the

interior walls were covered in red porphyry and green marble,

while the floor was made of slabs of white and green stone.

While Roger was popular with Henry I, however, he seems to have

ended up on the wrong side of the quarrel between Stephen and

Maud, and in 1139 Stephen arrested him and seized the treasure he

had put aside for rebuilding the cathedral. Roger died of a

fever shortly thereafter, whereupon Stephen plundered the

cathedral itself; in 1153, he also gave the order for the castle

to be destroyed, but this was never carried out.

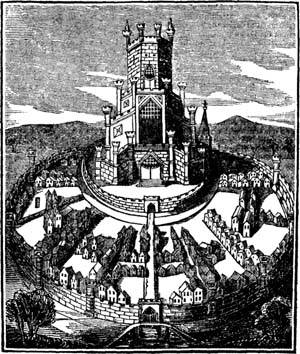

As Henry d'Avranches says in his poem about Salisbury, in Old

Sarum "the city was in the castle, and the castle, in the city.

The castle was subject to the laws of Caesar, the city to those

of God. The king's followers plundered the clergy."

Historically, Old Sarum is considered a castle, not a town; the

area between the motte and the outer earthworks, with its houses

and shops and cathedral and bishop's palace, was considered the

castle's "outer ward." When the king was not in residence (which

was pretty much most of the time), a guard was left to defend the

castle; in 1166, for example, one Earl Patrick owed the crown the

service of 40 knights, 20 of which were to be used in the defense

of Sarum. Royal visits occurred sporadically in the 12th and

13th centuries, and Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine was even

imprisoned in the castle for a period of time.

As d'Avranches' poem suggests, quite a bit of conflict

arose between castle and cathedral. The monks didn't enjoy

having to rent dwellings from the soldiers, and since the

soldiers controlled the gates, the monks complained that they

often prevented worshippers from entering. On one occasion, the

soldiers locked the monks themselves out of the castle precinct,

refusing to admit them to their own cathedralĐand this,

apparently, was the last straw for the current bishop, Herbert

Poore. It was time to leave Old Sarum and build a new cathedral

for Salisbury -- a plan approved by both King Richard I and the

pope. As d'Avranches' poem suggests, quite a bit of conflict

arose between castle and cathedral. The monks didn't enjoy

having to rent dwellings from the soldiers, and since the

soldiers controlled the gates, the monks complained that they

often prevented worshippers from entering. On one occasion, the

soldiers locked the monks themselves out of the castle precinct,

refusing to admit them to their own cathedralĐand this,

apparently, was the last straw for the current bishop, Herbert

Poore. It was time to leave Old Sarum and build a new cathedral

for Salisbury -- a plan approved by both King Richard I and the

pope.

But where? According to legend, the bishop decreed that an arrow

would be fired from the walls of the keep, and the new cathedral

would be built wherever it fell. Miraculously, however, the arrow

struck a passing deer, who fled a full two miles to the banks of

the Avon ("and that," as my husband muttered under his breath on

hearing the tale, "was where the second arrow hit it...").

Needless to say, this location was perfect for the new cathedral,

which was founded in 1220. The old cathedral was completely

dismantled for building stone; you can walk among its

foundations, or view them from the motte above.

By this time, most of the townsfolk had left Old Sarum, though

the castle remained, and was garrisoned and provisioned through

most of the 13th century. Thereafter it seems to have fallen

into disrepair, though periodically it would be repaired and

re-garrisoned in the face of some new threat, such as the threat

of a French invasion in 1339 and 1360. In the mid-1400's, the

town was still listed as having a mayor, but practically no

inhabitants; in 1514, Henry VII ordered the castle

demolished.

And there the history of Old Sarum might have ended, save for one

last shameful entry in the booksĐas the most notorious of all

"rotten boroughs." The term "rotten borough" was applied to

Parliamentary constituencies that were controlled by a single

person. Since the reign of Edward II, Old Sarum had the right to

send two members to the House of Commons, and the landowners

retained this right even though, by the 17th century, no one

actually lived in the borough. Thus, a handful of

absentee landowners were able to use Old Sarum as a means of

voting their own representatives into the House of Commons. The

borough's last election was held in 1831; "rotten boroughs" were

abolished by Reform Act of 1832.

Today, the blazing white chalk, said to have been bright enough

under the summer sun to blind the onlooker, is covered with soft

green grass. The wind still blows, but no longer drowns out the

songs of the monks in the cathedrals; now it seems a peaceful

sound. The hilltop is quiet, except for the laughter of children

scampering up and down the hillocks or climbing the walls, and

it's hard to imagine the strife that once beset this site, strife

that came more from within than from any threat outside the

walls. When you buy your ticket, you'll be invited to take a

"walking tour" of the site with a guide, but you'll find the same

information in the booklet available at the counter. (Our guide's

idea of a "walking tour" was to stand in one spot and

occasionally wave his hand vaguely in the direction of a distant

wall; hopefully other guides are more lively.) Whether you read

the guidebook or take the tour, you may feel, as you walk back to

the carpark, that you're walking through layers of time.

Related Articles:

- Salisbury: Designed to In-Spire, by Moira Allen

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/towns/salisbury.shtml

- Timeline: Salisbury, by Darcy Lewis

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/towns/saltime.shtml

- The Eternal Mystery of Stonehenge, by Pearl Harris

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/stones/stonehenge.shtml

- Stonehenge: The Giants' Dance, by Sue Kendrick

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/stones/stonehenge1.shtml

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Moira Allen has been writing and editing professionally for more than 30 years. She is the author of seven books and several hundred articles. She has been a lifelong Anglophile, and recently achieved her dream of living in England, spending nearly a year and a half in the history town of Hastings. Allen also hosts the Victorian history site VictorianVoices.net, a topical archive of thousands of articles from British and American Victorian periodicals. Allen currently resides in Maryland.

Article and photos © 2007 Moira Allen

|