Kirby Muxloe Castle -- Quadrangular Glory in Brick and Water

by Lise Hull

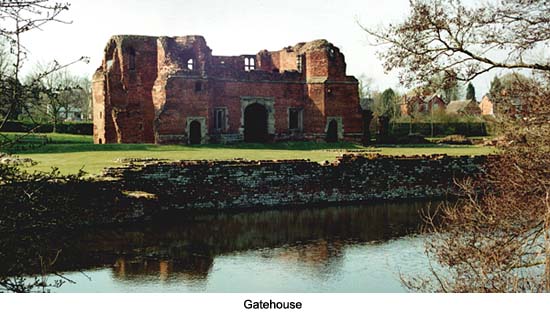

Situated just four miles due west of Leicester is Kirby Muxloe,

where one of England's most evocative ruins graces the

countryside. Constructed with 100,000 bricks fired on site rather

than with locally quarried stone, Kirby Muxloe Castle gleams a

fiery red on sun-filled days, the moat reflecting the brilliance

of the brickwork contrasted with the green lawns. Often

characterized as a fortified manor rather than a true castle,

Kirby Muxloe was one of the earliest brickwork castles erected in

England but was also one of the last of its type, a quadrangular

castle, to be built. Despite having never been completed, the

attractive site is an impressive tribute to its builder, William,

Lord Hastings, who for a time held a position of great power

within the realm.

Settled by the Danes as early as the 9th century, the spot was

identified as Carbi (Caeri's settlement) in the Domesday Book of

1086. The settlement grew gradually and by the 15th century, a

manor house stood on the site now occupied by the ruined castle.

In fact, the house may have been built in the early 14th century,

when the Hastings family first acquired the manor by right of

marriage between Sir Ralph Hastings and Margaret Herle, daughter

of Sir William Herle, who owned the manor.

Having leased the house for several years, William, Lord

Hastings, Edward IV's second cousin and Lord Chamberlain,

acquired the manor in 1474. He also obtained a license to

crenellate, but did not proceed with work on the castle until

1480. Sadly for Hastings, his political affiliations during the

Wars of the Roses, when he fought for Edward IV at the Battles of

Mortimer's Cross and Towton and even followed the king into exile

in 1471, eventually led to his downfall.

After Edward's death in 1483, Richard, Duke of Gloucester and the

king's brother, took the throne as Regent of England to rule on

behalf of the heir, Prince Edward (who was still in his

minority). Though still serving as Lord Chamberlain, within a few

months of the king's death, Hastings was charged with treason for

allegedly plotting against the Regent. Lord Hastings apparently

posed such a threat that, within a week of the arrest, Richard

had him beheaded on Tower Green. The execution was a first for

the Tower of London. Within a month, Richard seized the throne

for himself, declared the two heirs to the throne illegitimate,

and became King Richard III. Shortly after, the two boys, Prince

Edward and his younger brother, Richard, disappeared. Many

historians fault Richard III for the mysterious demise of the

"Princes in the Tower."

Despite William's execution, the Hastings family retained control

of the brickwork castle, and, for a time, continued the building

program, roofing the towers and installing floors. However, in

1484, Lady Hastings abandoned the burdensome effort. During the

reign of King Henry VII, which began the following year, Edward

Hastings, the rightful heir, regained the lordship.

Unfortunately, he never returned to complete the construction

work at the castle.

In 1630, Sir Robert Banaster acquired Kirby Muxloe Castle, but

did little to maintain it. In fact, masonry from the castle was

taken to build the neighboring farmhouse, now the Castle Hotel

(www.castlehotelkirby.com). In 1911, Major Richard Winstanley

placed Kirby Muxloe Castle under the guardianship of the Ministry

of Works, and is now managed by English Heritage. Conservation

work was done at the site during 2005.

The ruins today

Designed by master mason John Cowper, the original plan of the

quadrangular castle included towers built at the four corners and

a curtain wall surrounding the interior which linked the towers

to the gatehouse and also to other towers placed midway along

each wall. Around the entire built complex, a moat provided

defense against intrusion. A timber drawbridge originally spanned

the water-filled ditch and gave access to the gatehouse, which in

turn allowed entry into the inner ward via a single passageway.

The site now primarily consists of the gatehouse, the three-story

west tower, and the impressive moat.

The rectangular gatehouse now only rises a single story over

the gate passage. On the exterior, the red-and-black brickwork

diamond pattern and variety of carvings still illustrate the

prestige of the castle's owner. The finely crafted initials,

"WH," the Hastings coat of arms, a ship, and a male

figure still adorn the façade immediately above the

entrance. Interestingly, garderobes (latrines) emptied into

vaulted cesspits inside the gatehouse rather than into the moat,

as was typical at many castles, where the regular flow of the

water would have helped cleanse the site of waste.

Almost perfectly preserved to its original height, adorned with

battlements and composed of brickwork decorated with

red-and-black patterns, the West Tower was probably the one

structure Hastings managed to complete before his execution. The

unusual positioning of the gunports near the base of the tower

suggests that they were added more as a show of force rather than

to serve a real defensive function.

Only fragments of other building work have survived. Of

particular note, however, is the moat, which was lined with brick

and filled by water diverted from two brooks. To ensure the moat

filled and emptied properly, builders installed two masonry dams,

sluices and an intriguing set of hollow oak logs, which could be

blocked with leather-ringed wooden plugs. They also constructed a

screen across the mouth of one of the brooks to prevent blockage

from leaves and other debris. In the early 20th century, when

work was done to consolidate the site, one of the plugs, a

tapering block of wood covered with leather, was discovered in

place still doing its original job.

Terminology

- Quadrangular castle: As the designation implies,

a quadrangular castle had four sides, roughly equal in length,

which enclosed a square or rectangular courtyard (the inner

bailey). Each side may also have been fitted with wall towers

positioned along their length. A tower -- often round in plan --

dominated each corner and stood at least one story taller than

the curtain wall. The main gatehouse generally occupied a central

position on one of the sides. Many quadrangular castles were also

enclosed by a second, outer curtain wall. Although erected during

the late 13th century, quadrangular castles generally appeared

during the 14th and 15th centuries, late in the history of

British castle-building. Kirby Muxloe was quite possibly the last

quadrangular castle erected in England. Other examples include

Chillingham Castle in Northumberland, Bolton Castle, in

Yorkshire, and Bodiam and Herstmonceaux Castles in East

Sussex.

- License to crenellate: Although never mandated by the

monarchy nor a common practice until after 1200, applying for a

license to erect a castle or to fortify a standing residence

indicated not only that the applicant had the self-confidence to

approach the king, but also demonstrated that he possessed the

financial and personal status that came with the ability to build

a castle. For many lords, receiving the license to crenellate was

accomplishment enough, so they felt no urgency to complete the

process with an outlandish expenditure of money that could result

in bankruptcy. Just having the royal license proved they were

qualified to move in the circles of the rich and famous and that

the monarch recognized their social status.

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

|

Lise Hull is a recognized authority on British castles and heritage, with a Master of Arts degree in Heritage Studies from the University of Wales, Aberystwyth, as well as a Master of Public Affairs degree, specializing in Historic Preservation, from Indiana University. She is the author of several of books on Britain, including Britain's Medieval Castles (Praeger: 2005), Great Castles of Britain and Ireland (New Holland: 2005) and Castles and Bishops' Palaces of Pembrokeshire (Logaston Press, 2005). Her work has appeared in numerous publications, including Military History Quarterly, Military History, Renaissance Magazine, Family Tree Magazine and Everton's Family History and Genealogical Helper magazines; she is also a regular contributor to Faerie Magazine. Visit her website at http://www.castles-of-britain.com. Hull also writes TimeTravel-Britain.com's Finding Your Roots column.

|

Article and photos © 2005 Lise Hull

|