The Inspiring Walls of Kenilworth Castle

by Lise Hull

Situated on the western side of the sprawling yet attractive town of the same name in Warwickshire, Kenilworth Castle's hulking ruins dominate its surroundings. In its heyday, this skillfully engineered combination of water defenses and walls-within-walls made it one of England's most powerful castles -- and the inspiration for Britain's greatest concentric castle, at Caerphilly, Wales. Today, the sharp contrast between the rugged red walls against the green grassland at their base startles visitors' senses just as it did in 1821, when those walls inspired Sir Walter Scott to write a novel of the same name.

Originating in the late 11th or early 12th century, Kenilworth's massive stone enclosure castle (see "Castle Terminology," below) features elements from nearly every era of British castle-building. The basic shape of the site and the the massive rectangular keep reflect the castle's medieval origins, while the skillfully carved mullion windows and showy Leicester Gatehouse demonstrate the flamboyance of the Elizabethan era. The marshy grassland that now surrounds the ruins was once a scenic lake and giant moat known as the Great Mere, created in the early 13th century by damming the waters of the neighboring Finham and Inchford Brooks. This Great Mere was a key part of the castle's defensive system.

In the early 13th century, Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, led a group of noblemen in a rebellion against his brother-in-law, King Henry III, and used Kenilworth Castle as his main headquarters. Though de Montfort died during the Battle of Evesham in 1265, his son, also named Simon, continued the uprising. Enraged by the rebels' defiance, Henry's son, Prince Edward, led the royalist army to Kenilworth and besieged the castle in 1266. Kenilworth Castle's stone and water defenses were so powerful, however, that even though the attackers assaulted the stronghold with eleven siege engines (or catapults), hundreds of archers and a fleet of barges, the enormous size of the 111-acre Great Mere made it virtually impossible to conquer the castle. When Prince Edward's army finally achieved victory after nine months, it was not not firepower, but disease, that overcame the castle's defenders.

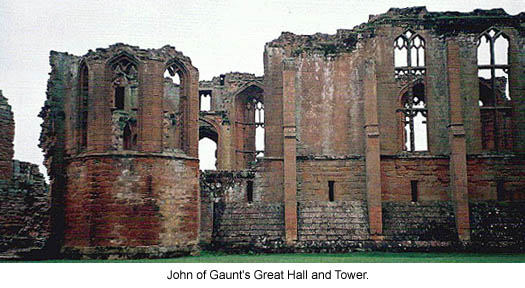

In the late 14th century, John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster and father to King Henry IV, began converting the castle into a palatial dwelling that melded grandeur and comfort with powerful defenses. In 1553, Edward VI granted the castle to John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland and Earl of Warwick. After the king's untimely death the same year, Dudley unwisely supported Lady Jane Grey as queen of England (for a brief nine days), but lost his head when the rightful queen, Bloody Mary Tudor, seized the throne and reclaimed Kenilworth Castle for the monarchy. Ten years later, Mary's sister, Queen Elizabeth I, made amends by awarding the grand fortress to her favorite courtier, Robert Dudley, John's heir and Earl of Leicester. Dudley completed the castle's transition into one of England's greatest palatial fortresses.

In 1575, Robert Dudley honored Elizabeth (and her entourage of several hundred people) with 19 days of festivities, including feasts and a fantastic water spectacle. Using the Great Mere as the backdrop, Dudley organized masques, fireworks, hunting and bear-baiting, musical entertainment, dancing, mystery plays (based on biblical stories), and plenty of food and wine. The enormous expense of entertaining the queen actually bankrupted the earl, but he undoubtedly thought it money well spent.

In 1575, Robert Dudley honored Elizabeth (and her entourage of several hundred people) with 19 days of festivities, including feasts and a fantastic water spectacle. Using the Great Mere as the backdrop, Dudley organized masques, fireworks, hunting and bear-baiting, musical entertainment, dancing, mystery plays (based on biblical stories), and plenty of food and wine. The enormous expense of entertaining the queen actually bankrupted the earl, but he undoubtedly thought it money well spent.

After Dudley's death in 1588, the castle changed hands several times and soon began to decay. Yet it remained strong enough that, after the end of the English Civil War in 1649, Oliver Cromwell's parliamentarian troops "slighted" the stronghold, demolishing large portions of the masonry walls to make it useless for further military service. The castle that survives today looks much as it did when Cromwell's men ravaged the defenses and drained the Great Mere.

Exploring Kenilworth Castle

When visiting the grand ruins, be sure to look beyond the castle itself for relics of Kenilworth's medieval and renaissance past. Wander the footpaths and enjoy the parkland that now occupies the landscape once flooded by the Great Mere. Explore the earthworks known as the Brays and note the traces of the castle fishponds, which mark the site's medieval boundaries near the car park. And, almost due east of the castle and closer to the town of Kenilworth, visit the remains of a medieval abbey destroyed by Henry VIII during the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1536. Partly rebuilt by Robert Dudley, the abbey's chancel (the section containing the altar and seats for the clergy and choir) was used by Queen Elizabeth I.

When visiting the grand ruins, be sure to look beyond the castle itself for relics of Kenilworth's medieval and renaissance past. Wander the footpaths and enjoy the parkland that now occupies the landscape once flooded by the Great Mere. Explore the earthworks known as the Brays and note the traces of the castle fishponds, which mark the site's medieval boundaries near the car park. And, almost due east of the castle and closer to the town of Kenilworth, visit the remains of a medieval abbey destroyed by Henry VIII during the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1536. Partly rebuilt by Robert Dudley, the abbey's chancel (the section containing the altar and seats for the clergy and choir) was used by Queen Elizabeth I.

Today, Kenilworth Castle is managed by English Heritage. The site is open to the public on most days of the year, for a fee. Kenilworth and its palatial fortress sit in the heart of the English Midlands, about eight miles north of Warwick in the county of Warwickshire, and less than ten miles southeast of Birmingham.

What to See

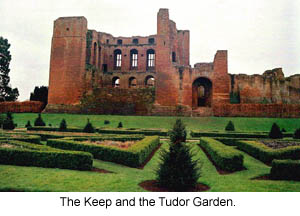

- The 12th century rectangular keep features 17-foot thick walls and four 100-foot high towers.

- Additions by John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster: the huge great hall complex and immense residential block.

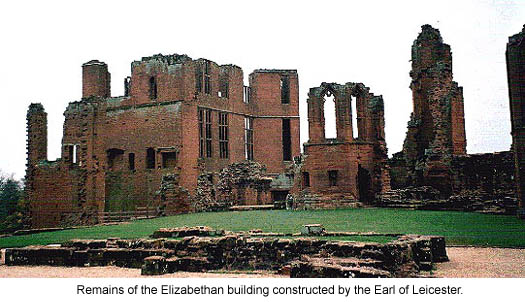

- Alterations by Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester: Leicester's Gatehouse (presently being restored), Leicester's Building (which probably housed his queen in 1575) and the half-timbered stable block.

- The reconstructed Tudor garden, originally planted by Robert Dudley.

- Stone balls fired during the siege of 1266, mounted on brick walls alongside the garden.

- Henry V's pleasaunce, or banqueting house - only earthworks and the moats survive; located northwest of the main castle site.

Castle Terminology

- Stone enclosure castle: Often erected on top of an earlier, more simply constructed castle or within the defenses of an abandoned Roman fortress or Iron Age hillfort, stone enclosure castles generally featured reasonably strong masonry walls equipped at intervals with rectangular or cylindrical mural towers. The curtain wall enclosed a bailey, or courtyard, which held the most vital residential and military structures. Stone enclosure castles typically contained a moat or dry ditch, at least one drawbridge and gatehouse, the circuit of towered walls, and, often, as at Kenilworth, the great keep.

- Keep: a self-sufficient, fortified tower containing living quarters that could also used as a refuge in a siege.

- Siege engines: timber machines for firing missiles at a castle or for scaling walls.

- Mullion: vertical bar of stone or wood dividing a window into smaller openings.

- Garrison: a group of soldiers stationed at a castle.

- Great hall: a castle's entertainment center, where the lord and his family dined and guests feasted; also used as the main administrative chamber.

- Parliamentarian: supporters of the English Parliament who fought against the Royalists during the English Civil War in the 17th century. At the time, Charles I was king and the Parliamentarian leader was Oliver Cromwell.

- Royalist: supporters of the monarchy.

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

|

Lise Hull is a recognized authority on British castles and heritage, with a Master of Arts degree in Heritage Studies from the University of Wales, Aberystwyth, as well as a Master of Public Affairs degree, specializing in Historic Preservation, from Indiana University. She is the author of several of books on Britain, including Britain's Medieval Castles (Praeger: 2005), Great Castles of Britain and Ireland (New Holland: 2005) and Castles and Bishops' Palaces of Pembrokeshire (Logaston Press, 2005). Her work has appeared in numerous publications, including Military History Quarterly, Military History, Renaissance Magazine, Family Tree Magazine and Everton's Family History and Genealogical Helper magazines; she is also a regular contributor to Faerie Magazine. Visit her website at http://www.castles-of-britain.com. Hull also writes TimeTravel-Britain.com's Finding Your Roots column.

|

Article and photos © 2005 Lise Hull

|