Well-Dressing in Derbyshire

by John Ravenscroft

The man I saw pressing flower petals into damp

clay back in 1974 was a giant. He had shoulders like a prize

bull, hands like a pair of hams, and it was hard to believe he

could handle those fragile flower petals with such delicacy. But

when he stepped away from the frame and showed the watching crowd

the results of his efforts, there was a warm buzz of admiration.

He'd done an excellent job, and knew it. In my memory, he's still

taking his bow. The man I saw pressing flower petals into damp

clay back in 1974 was a giant. He had shoulders like a prize

bull, hands like a pair of hams, and it was hard to believe he

could handle those fragile flower petals with such delicacy. But

when he stepped away from the frame and showed the watching crowd

the results of his efforts, there was a warm buzz of admiration.

He'd done an excellent job, and knew it. In my memory, he's still

taking his bow.

Thinking back over thirty years to that pleasant, late-May,

Derbyshire afternoon, I'm aware that memory is unreliable. In

reality, I don't suppose my Flower Man was really seven feet

tall, and no doubt his fingers were only half the size they've

since become in my imagination -- but he was certainly big enough

to create a lasting impression. The contrast between his great

size and the delicate nature of his task that afternoon made me

grin -- and remembering it now, I'm grinning again. I

never found out who my large friend was -- probably a local

resident -- but whoever he was I'd just happened to catch him

taking part in a ceremony that's been a feature of Derbyshire's

Peak District for hundreds of years, and one that continues to

this day: the time-honoured custom of Well Dressing.

Water is one of our most basic requirements, so it's no

surprise that springs and wells have long been venerated by the

ordinary people who've used them for generations. The custom of

Well Dressing is an attractive demonstration of that

veneration.

During the Black Death of 1348-1349, when perhaps one third of

the population of England died, some Derbyshire villages escaped

untouched. One theory regarding the origin of Well Dressing in

Derbyshire suggests that local people who had been spared felt

their water supply was the cause of their good fortune, and began

decorating their village wells as an act of thanks. However a

pagan root seems more likely, especially given the fact that a

feature of many of these Dressings is the crowning of the 'Well

Queen' Ñ a probable echo of ancient fertility rights.

In Pagan

times it was the norm to make sacrifices to the water gods.

Without their good favour the precious sources of water might

stop flowing, and if that happened the land would become

infertile. Famine would swiftly follow. So for centuries

chickens, goats and even human beings were offered up as a

sacrifice to the water gods, but over time these gory practices

died out and the far more civilized custom of hanging green

branches and garlands of flowers over the spring or the well was

adopted instead. In Pagan

times it was the norm to make sacrifices to the water gods.

Without their good favour the precious sources of water might

stop flowing, and if that happened the land would become

infertile. Famine would swiftly follow. So for centuries

chickens, goats and even human beings were offered up as a

sacrifice to the water gods, but over time these gory practices

died out and the far more civilized custom of hanging green

branches and garlands of flowers over the spring or the well was

adopted instead.

In this way, Well Dressing was born.

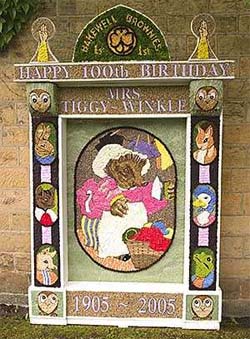

The arrival of Christianity was initially bad news for

well-dressers. Water-worship was strictly forbidden -- so much so

that Henry VIII's Chancellor, Thomas Cromwell, oversaw the

destruction of all the well dressing equipment his men could

find. During Henry's reign, a number of crippled

water-worshippers visiting the well at Buxton in Derbyshire in

hopes of a cure had their crutches confiscated and destroyed.

Gradually, however, the ancient springs and wells lost their

pagan associations and were rededicated to one or another of the

Christian Saints (or more recently to other beloved and

"acceptable" characters, such as Beatrix Potter's Miss

Tiggy-Winkle, left). The people could once again decorate their

wells with flowers and greenery, as long as they did it in a

Christian fashion, and as an act of thanksgiving to God for the

gift of water.

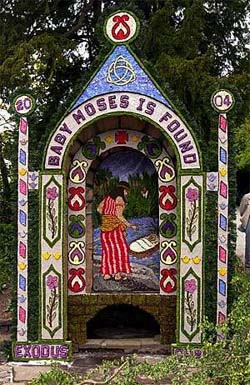

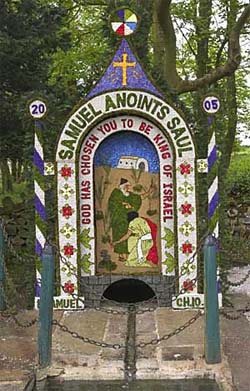

It's not surprising, therefore, that when well-dressing became

rather more arty and pictures began to appear, many of the

subjects of those pictures had a religious theme. That remains

the case to this day, and in most of the villages that still

practice the custom the decorated wells are still blessed by

church officials. There's a carnival atmosphere, and a brass band

often provides a little music to add to the sense of

occasion.

So what are the practicalities? How do you go

about dressing a well? So what are the practicalities? How do you go

about dressing a well?

In pagan times, it was a simple affair. You gathered flowers,

berries and greenery and fashioned them into garlands, and you

used these garlands to pretty-up your well. But from about 1818

something new began to happen. Wooden frames some five feet wide

and six feet high appeared. They held a base of moist clay

perhaps one inch deep, which was prevented from drying out by

immersing the entire frame in water for a week before it was due

to be used. This was a process known as 'puddling'.

The construction of these clay-holding frames was the first stage

in creating the new-style Well Dressings. The next steps in the

process are the same now as they were back in the 1800s. The

chosen design is drawn on sheets of paper the same size as the

frame, and the paper is carefully placed on top of the damp clay.

By pricking through with a skewer, the design is transferred to

the clay, and then the paper is peeled off.

The resulting outline is marked out with black wool, which is

pushed into place with a knitting needle, and a team of

well-dressers then begins the long, slow process of building up

the design. Working from the base of the frame upwards, the team

presses flower-petals, leaves, berries, bark etc. into the clay

and gradually the picture takes shape. Obviously, because designs

vary in size and shape, the time taken to construct a Well

Dressing varies -- but an average example may take a team of

twenty people seven days to complete.

Once finished, the Well Dressing has to be transported to the

well site, where it stays in place for a week or so, although its

actual life depends very much upon the English weather. Hot,

windy conditions can do a great deal of damage to these delicate,

flower-petal pictures, despite the water-spraying efforts of

locals like my oversized Flower Man who have worked so hard to

create them. If memory serves I last saw Flower Man

sharing a pint of bitter with his friends outside one of the

village pubs, and as you'd expect the landlords are always keen

to offer refreshment to the many visitors drawn to the area by

Derbyshire's Well Dressings. After all, flower-arranging can be

pretty thirsty work!

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

John Ravenscroft is a teacher-turned-writer who lives in Lincolnshire, England. He spends much of his time struggling to write fiction and co-editing Cadenza Magazine. His short stories have won prizes in various literary competitions and been published in numerous magazines, and his work has also been broadcast on the BBC. In 2005 he is planning to write more nonfiction articles. Visit his website at http://www.johnravenscroft.co.uk.

Article © 2006 John Ravenscroft

Photos © Edward Rokita

|