Where Robin Wed Marian: St. Mary's of Edwinstowe

by Julia Hickey

This is the church where legend says that Robin Hood married Maid Marian. Situated at the heart of Sherwood Forest, less than a mile from the Major Oak -- Robin's reputed hiding place -- it is easy to see how the tale took root in popular imagination.

This is the church where legend says that Robin Hood married Maid Marian. Situated at the heart of Sherwood Forest, less than a mile from the Major Oak -- Robin's reputed hiding place -- it is easy to see how the tale took root in popular imagination.

Yet the story of St Mary's is far older than that of the outlaw who stole from the rich to give to the poor. In 633 AD, King Edwin of Northumbria, the second Christian king of England was killed at the Battle of Heathfield by Penda, King of Mercia. Edwin's followers carried the body of their king from the battlefield; decapitated it; buried the body where Penda would not find it; then took the head of their monarch back to York, where it was buried in St Peter's Cathedral.

By the time Edwin's supporters were able to return for the body, which was eventually buried at Whitby Abbey, Edwin was revered as a saint. The place where his body had lain was hallowed ground. A small wooden chapel was built on the spot and Edwinstowe -- or Edwin's place -- was born.

Of the wooden structure there remains no sign. The story of the stone church begins with the death of another saint -- Thomas á Becket, who was martyred in Canterbury in 1170 by four knights. Henry II may well have rid himself of a turbulent priest, but he was to pay a heavy price for the deeds of his men at arms. The king's barefoot penance and public scourging at the tomb of the saintly archbishop is history. Less well known is the building programme that Henry undertook as part of his act of contrition. Edwinstowe, in the Royal Forest of Sherwood, is within three miles of the ruins of the Royal Hunting Lodge at Clipston, and by 1175 Edwinstowe possessed a church built from stone. The debt that St Mary's owes to Thomas á Becket and Henry II is recognised by the addition of two carved stone heads in the nave of the church depicting the king and his archbishop.

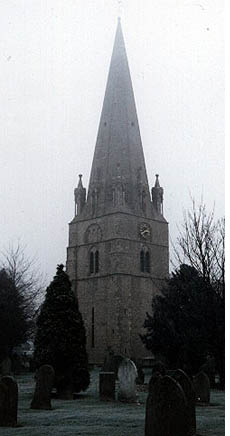

Visitors can still see the ghostly shadow of that first modest stone church by looking up at the wall of the stoutly built bell tower. Evidence of a sloping roof can be seen in the stonework. And don't forget to look at the two columns nearest the tower. Each of the columns is capped by a stone corbel shaped into a grimacing face. One seems to be crosseyed, whilst the second, a rather unladylike character, is sticking her tongue out at her companion.

Visitors can still see the ghostly shadow of that first modest stone church by looking up at the wall of the stoutly built bell tower. Evidence of a sloping roof can be seen in the stonework. And don't forget to look at the two columns nearest the tower. Each of the columns is capped by a stone corbel shaped into a grimacing face. One seems to be crosseyed, whilst the second, a rather unladylike character, is sticking her tongue out at her companion.

The north aisle was added to the nave at the end of the 12th century. It is here that visitors can find the grave slab -- sometimes called a body stone -- of a priest. It is partially concealed by the organ chamber, but one can still see the cross and chalice that denote the occupation of the person it commemorates.

This aisle also houses the Forest Measure, which can be found to the left of the Rigley memorial. Traditionally this measure was used as a standard foot. It was originally placed outside the church, but was removed from its position next to the Priest's Door in 1911 for fear of weathering. Evidence suggests that it is in fact a piece of broken string course, but this did not prevent it from being used as the standard by which land was measured to calculate rent as recorded in the register of Newland Abbey in the time of Edward I.

Visitors can also see the anguished figure of Christ upon the cross. This bronze crucifix is a memento of the First World War. Soldiers returning from the horrors of Flanders brought this symbol of suffering and redemption, which once stood at some wayside shrine, back to the peace of the parish church where their ancestors had worshipped for over 700 years.

The south aisle was built in the 14th century by Henry de Edwinstowe, who founded a chantry chapel dedicated to Our Lady and St Margaret of Antioch -- a female dragonslayer. The evidence for this is well documented but is also testified to by the architecture that can be viewed. There are two aumbries (priest's cupboards) built into the wall near the altar and a piscina (a kind of hand basin).

The stone altar with its dedication crosses was once hidden beneath the floor of the bell tower. One suspects that the people of Edwinstowe, or at least some of them, did not wish to cast aside their old beliefs with the coming of the Reformation and Elizabeth I's edict commanding the use of plain wooden tables rather than the old stone altars. Interestingly. the vicar of Edwinstowe -- one Henry Tinkar -- had gained the living of the parish during the reign of Elizabeth's Catholic sister Mary. He continued in this role throughout his life, so it is probable that he hid the altar, turning it face down to look like a grave slab.

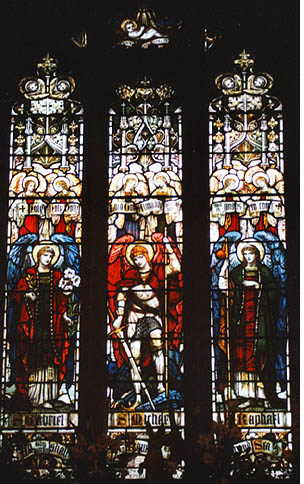

The 19th-century window above the altar in the south aisle is vibrant and easily the most beautiful window in the church. It is a memorial to Captain Alexander of the 17th Lancers. Moving to the chancel, the east window is also 19th-century in design, but makes use of older glass. Look for a painted face peeping out from a pane of glass towards the bottom of the central section on what should be an undecorated area!

The 19th-century window above the altar in the south aisle is vibrant and easily the most beautiful window in the church. It is a memorial to Captain Alexander of the 17th Lancers. Moving to the chancel, the east window is also 19th-century in design, but makes use of older glass. Look for a painted face peeping out from a pane of glass towards the bottom of the central section on what should be an undecorated area!

The chancel also contains a pillar piscina. Essentially a piscina is a hand basin for priests. Piscina is Latin for "reservoir of water". Piscinas were either wall-mounted like the one in the south aisle or were placed on columns -- a bit like a modern wash basin. Edwinstowe's pillar piscina is unusual not only because of its size but also because it is the only known example of the Early English period. Before leaving the chancel, take a moment to note the oak alter rail, which is a memorial to the Reverend F Day-Lewis, father of the poet laureate Cecil and grandfather of the actor Daniel Day-Lewis.

The font, by the south door, is 14th-century. Behind it is a remnant of the old christening and churching seat -- a reminder of the times when a cleansing was an essential ritual for women who had just given birth. Alongside this twisted piece of wood with its curious history is a list of Edwinstowe's priests.

The solid-looking octagon-shaped font shows signs of having taken a real battering during its life. Much of the damage was probably done when the spire came crashing down after being struck by lightening. The broach spire -- added to the top of the bell tower in the 15th century -- has been struck by lightening at least three times in its life. The first strike, in 1672 or 1673, caused the most damage, causing the spire to topple down into the nave. The people of Edwinstowe had to write to Charles II seven years later to ask for funds to complete the restoration. Charles allowed them to fell 200 oaks, provided the trees were unsuitable for naval vessels. The spire was damaged again in 1815 and in 1871.

Outside the church, there are three graves that visitors may want to take time to find. One tells the tragic tale of John Birdsall and Richard Neil, who drowned in Thoresby Lake in 1800. The second belongs to a Bow Street Runer -- an early policeman -- who died in 1841. The third grave, to the west of the tower, is the grave of the Rev. Dr. Ebenezer Cobham Brewer, an incumbent of Edwinstowe who died in 1897 and famous for his Dictionary of Phrase and Fable.

Disappointed that there is no further mention of Robin or his Merry Men? Why not walk down the High Street to find the statue of Robin and Marian, or tarry awhile in the Green Wood, which offers some pleasing walks of varying lengths as well as a glimpse of that famous oak?

The Major Oak

The Major Oak is a huge Oak tree near the village of Edwinstowe in the heart of Sherwood Forest, England. According to local folklore, it was Robin Hood's headquarters. It weighs an estimated 23 tons, has a waistline of 33 ft and is about 800-1000 years old.

There are several theories concerning why it became so huge and oddly shaped:

- The Major Oak is, in fact, several trees that fused together when saplings.

- The tree was pollarded, a system of tree management that enabled foresters to grow more than one crop of timber from a single tree causing the trunk to grow large and fat.

It took its present name from Maj. Hayman Rooke's description of it in 1790.

The Major Oak is probably the most famous tree in the western world. In 1998 a local Mansfield resident was cautioned by the Nottinghamshire Police for selling alleged Major Oak acorns (including a certificate of authenticity) to unsuspecting Americans via an Internet based mail-order company.

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Julia Hickey is passionate about England's heritage and particularly of Cumbria, where her husband comes from. In between dragging her family around the country to a variety of historic monuments, she works part-time as a senior lecturer at Sheffield Hallam University. She spends the rest of her week writing. In her spare time, she enjoys walking, dabbling in family history, cross-stitch, tapestry and photography.

Article & photos © 2005 Julia Hickey

Major Oak text and photo courtesy of Wikipedia.org.

|