A Medieval Christmas

by Jane Gilbert

When we think of medieval Christmas, our minds are filled with

images of royal banquets in halls bedecked with green, of

minstrels singing festive songs, noble lords and ladies gorging

themselves on roast goose. We imagine snow-topped hills, and

fresh bright mornings, where the differences between rich and

poor could be momentarily overlooked. Is it wrong to romanticize

like this? There is evidence to suggest that our imaginations

aren't far off the mark.

An Ancient Festival

The word 'Christes Maesse' surfaced in a Saxon book in 1038. But

the roots of this festival stretch back much earlier. In late

antiquity Christmas was not a time of revelry and fun, but

instead a time for a special mass, quiet prayer and reflection.

Until the fourth century, the church hadn't even fixed a date for

Christmas. Eventually, Pope Julius I chose December 25th. It

seems likely this was an attempt to christianize a pagan holiday

that fell on that date. Medieval folk were no strangers

to Christmas excitement. William the Conqueror was crowned King

of England in Westminster Abbey on Christmas day in 1066. This

was such a momentous occasion that the cheering inside the Abbey

made the guards outside think the king was being attacked. They

ran to his assistance and the coronation ended in a riot, with

people killed and houses burned.

But in Medieval times 25th December wasn't the most important

date: Epiphany was celebrated with more gusto. Some people say

that this day, 6th January or twelfth night, is to celebrate

Christ's baptism, others that Epiphany marked the visit of the

three kings bearing gifts to the baby Jesus. Some people forget

that Christ was born at Christmas, but they don't forget the gift

giving. While the kings may have brought gold, frankincense and

myrrh instead of Nike trainers and Playstations, the tradition

they started continues today.

The medieval holiday of Christmas is an amalgamation of Christian

and pagan, old and new. In the pagan festival of Yule, druids

blessed and burned a log and kept it burning for twelve days as

part of the winter solstice. The church has its own version of

this -- Candlemas, or the Feast of the Purification of the Virgin

held on 2nd February. Medieval parishioners came to church with a

penny and a candle to be blessed. Other candles were taken away

to comfort the sick and dying or to give hope during

thunderstorms. The Yule log gave the pagans a symbolic light to

guide them through the harsh winter, while the Candlemas candle

gave Christians solace in times of cold and hunger. The joining

of these two traditions meant ordinary people could celebrate the

birth of Christ and their own salvation, as well as enjoy

themselves with the feasting and fun associated with pagan

tradition.

The medieval holiday of Christmas is an amalgamation of Christian

and pagan, old and new. In the pagan festival of Yule, druids

blessed and burned a log and kept it burning for twelve days as

part of the winter solstice. The church has its own version of

this -- Candlemas, or the Feast of the Purification of the Virgin

held on 2nd February. Medieval parishioners came to church with a

penny and a candle to be blessed. Other candles were taken away

to comfort the sick and dying or to give hope during

thunderstorms. The Yule log gave the pagans a symbolic light to

guide them through the harsh winter, while the Candlemas candle

gave Christians solace in times of cold and hunger. The joining

of these two traditions meant ordinary people could celebrate the

birth of Christ and their own salvation, as well as enjoy

themselves with the feasting and fun associated with pagan

tradition.

But it wasn't fun for everyone. Childermass

or Holy Innocents Day was on December 28th -- the day King Herod

ordered the killing of all boys under the age of two in an

attempt to kill Jesus. While nowadays we might expect youngsters

to be playing with their new toys over the holiday season, in

medieval times they were cowering in cupboards. That's because in

medieval England, children were reminded of Herod's cruelty by

being beaten. Many thought December 28th a day of bad luck.

People were reluctant to get married on that day, or start

building something and Edward IV refused to be crowned. But it wasn't fun for everyone. Childermass

or Holy Innocents Day was on December 28th -- the day King Herod

ordered the killing of all boys under the age of two in an

attempt to kill Jesus. While nowadays we might expect youngsters

to be playing with their new toys over the holiday season, in

medieval times they were cowering in cupboards. That's because in

medieval England, children were reminded of Herod's cruelty by

being beaten. Many thought December 28th a day of bad luck.

People were reluctant to get married on that day, or start

building something and Edward IV refused to be crowned.

One example of the heady mix of Christian and pagan is the

tradition of the Lord of Misrule. This was someone appointed at

Christmas to be in charge of Christmas revelries, which often

included drunkenness and wild parties in the tradition of Yule.

Again, the church had an equivalent, called a boy bishop. This

tradition seems to come from ancient Rome, from the feast of

Saturnalia. During this time, the ordinary rules of life were

turned upside down. Masters served their slaves, and offices of

state were held by peasants. The Lord of Misrule presided over

all of this and had the power to command anyone to do

anything.

In the church, on January 1st's Feast of Fools, similar

strangeness occurred. Priests wore masks at mass, sang lewd songs

and ate sausages before the altar. It was a time of such wildness

that lords often employed special guards to protect their

property in case of rioting. Tenants of a manor belonging to

London's St Paul's Cathedral were obliged to keep watch over the

manor house, and were paid with a fire, a loaf of bread, a cooked

dish and a gallon of ale -- a sumptuous Christmas dinner.

Food for Thought

But what was medieval Christmas actually like? It was certainly

the longest holiday of the year, and brought with it cruelties as

well as privileges. Poorer people were let off work for the

festival, and sometimes were even treated to a Christmas dinner

in their landlord's great hall.

If you were lucky, that is. Some manors dished out Christmas

treats depending on status. One manor near Wells Cathedral in the

south of England invited two 13th-century peasants -- one a large

landholder and the other a small one. The first got a feast for

himself and two friends, including beer, beef and bacon, chicken

stew, cheese -- and even candles to light the feast with. The

poorer peasant did not fare so well. He had to bring his own cup

and plate. But at least he got to take home the leftovers, and he

was even given a loaf of bread to share with his neighbours. This

was used to play a traditional Christmas game. A bean was hidden

in the loaf and the person who found it became king of the feast.

This has turned into today's tradition of hiding pennies in

Christmas puddings to symbolize coming riches -- even if a penny

won't pay the dentistry bills for cracked teeth.

If you were higher on the social scale and were part of a

knight's household, or even the royal one, you would be treated

to a fabulous feast and gifts of jewels and robes. In 1482, the

famously generous King Edward IV gave a spectacular Christmas

gift to his people when he held a banquet that fed over two

thousand people each day. Even then the pressures to give at

Christmas were immense. Edward's brother, the notorious Richard

III had to sell items from the Royal household, and used items

from the treasury as pledges for loans in order to live up to his

brother's reputation. With the money he made, Richard presented

the city of London with a gold cup encrusted with jewels. He and

his wife Anne spent a staggering 1200 pounds on new clothes and

gifts for the court. He even licensed a merchant to bring jewels

into England -- as long as he had first choice so he could give

his wife impressive gifts.

But these weren't the only gifts given at Christmas. Famous

medieval chronicler Matthew Paris records that in 1249 King Henry

III got from London citizens 'the first gifts which the people

are accustomed superstitiously to call New Year's gifts.'

Portents of success for the coming year, these gifts are also

related to the modern tradition of 'first footing', where the

first person to set foot inside your house determined your

family's fortunes for the year.

On Boxing Day, rich lords often gave their tenants a small gift,

containing a moral lesson. The poor received money from their

masters in hollow clay pots with a slit in the top. You had to

break them to get the money out. Nicknamed 'piggies' these

offerings were the earliest version of a piggy bank, although it

is doubtful whether they encouraged much saving.

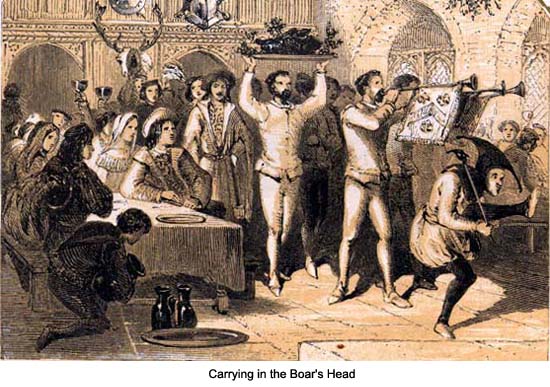

If you were lucky enough to be present at a noble Christmas

banquet, you would have your fill of sumptuous starters and tasty

treats. Medieval noblemen often had a boar's head as their main

dish, served with rosemary and an apple or an orange in its

mouth. In the countryside it was traditional to kill a wild boar,

cutting off its head and offering it to the goddess of farming to

ensure a good crop in the coming year. But if boar was elusive,

you might have goose or venison. You might even be served with

swan, smothered in butter and saffron -- with the King's

permission, that is. (They are still royal property today.)

If you were lucky enough to be present at a noble Christmas

banquet, you would have your fill of sumptuous starters and tasty

treats. Medieval noblemen often had a boar's head as their main

dish, served with rosemary and an apple or an orange in its

mouth. In the countryside it was traditional to kill a wild boar,

cutting off its head and offering it to the goddess of farming to

ensure a good crop in the coming year. But if boar was elusive,

you might have goose or venison. You might even be served with

swan, smothered in butter and saffron -- with the King's

permission, that is. (They are still royal property today.)

Less fancy tables would have to make do with whatever was left.

Though not allowed to eat the best parts of the deer, a nobleman

full of Christmas spirit might allow his poor tenants to have the

leftovers. Known as 'umbles,' these parts were usually the heart,

liver, tongue, feet, ears and brains. They were made into a pie.

It's easy to see where our modern expression about having to 'eat

humble pie' comes from. However, if you weren't into deer

entrails, the church generously offered a fixed Christmas price

of 7 pence for a ready cooked goose -- although that was about a

day's wages.

Mince pies were also eaten at medieval tables. If you made a wish

with your first bite people said it would come true. But don't

refuse if someone offers you a pie, or you might suffer bad luck.

Another big treat of the medieval table was Christmas pudding.

Called 'frumenty' -- from the Latin for corn 'frumentum' -- it

was made of thick porridge, wheat, currants and dried fruit. If

available, eggs and spices like cinnamon and nutmeg were

added.

To wash down all this rich food there were two fine festive

tipples. Lambswool was a hot concoction of mulled beer with

apples bobbing on the surface. There was also Church Ale, a

strong brew reserved only for Christmas and sold in the

churchyard or even in the church itself.

Christmas Carousing

The proximity of alcohol to the church coincides with one or two

of the more lively Christmas traditions. Carols, such a staple

part of today's Christmas diet, were prohibited in many European

churches because they were considered lewd. They were often

accompanied by dancing. The leader of the carol dance sang a

verse of the carol, and a ring of dancers responded with the

chorus. However, carol dances were suggestive of the fertility

traditions of pagan song and dance cycles, and were thus

considered too coarse for church.

A famous Christmas song of today is The Twelve Days of

Christmas, where a list of presents given to the singer by

their 'true love' is recounted. The gifts range from 'eleven

lords a-leaping' to 'a partridge in a pear tree.' In medieval

times this was a game set to music. One person sang a stanza,

then another would add his own lines to the song after repeating

the first person's verse. One tradition says it was a catechism

memory song. It helped Catholics in post-restoration England

remember facts about their faith at a time when practising it

could get them killed.

Another popular form of Christmas entertainment was 'mumming'.

Similar to modern English pantomimes, these were unceremonious

plays without words which usually involved dressing up as a

member of the opposite sex and performing comic tales. They took

place throughout the twelve days of Christmas, and involved

members of the troupe parading the streets and visiting houses

for dancing and dicing.

Of course, Christmas wouldn't be Christmas without festive

decoration. A description of twelfth century London says that

"every man's house, as also their parish churches, was decked

with holly, ivy, bay, and whatsoever the season of the year

afforded to be green." Whilst our gaudy modern decorations

would have confused a medieval person, they were still fond of a

bit of greenery to brighten up the murk of winter. Christians

believed that traditional Christmas plant, holly, had white

berries that turned red when Christ was made to wear the crown of

thorns. But holly was also important to the druids. So was

mistletoe, under which we still forge romantic encounters today.

Ivy, a plant associated with Bacchus, Roman god of wine and

carousing, was forbidden by the church because of its immorality.

(For more details, see The Holly

and the Ivy, by Julia Hickey.)

Of course, Christmas wouldn't be Christmas without festive

decoration. A description of twelfth century London says that

"every man's house, as also their parish churches, was decked

with holly, ivy, bay, and whatsoever the season of the year

afforded to be green." Whilst our gaudy modern decorations

would have confused a medieval person, they were still fond of a

bit of greenery to brighten up the murk of winter. Christians

believed that traditional Christmas plant, holly, had white

berries that turned red when Christ was made to wear the crown of

thorns. But holly was also important to the druids. So was

mistletoe, under which we still forge romantic encounters today.

Ivy, a plant associated with Bacchus, Roman god of wine and

carousing, was forbidden by the church because of its immorality.

(For more details, see The Holly

and the Ivy, by Julia Hickey.)

The story of Christmas trees also has long roots. The oak was

sacred to the druids and the Romans thought evergreens had

special powers. But for both pagans and Christians, the fact that

the fir tree kept its green needles throughout the ravages of

winter was enough for it to earn a place as a symbol of life and

renewal. This hope was vital whether you were celebrating the

birth of Christ or just desperately looking forward to the first

sign of spring. Even today we focus on them for Christmas

merriment.

Oliver Cromwell and his Puritan government tried to ban the

frivolities of Christmas and some of the more vernacular

traditions which developed during medieval times. But he didn't

succeed for long. Many of our modern traditions come from the

early mingling of the Christian and the pagan worlds. Whilst the

church secured Christmas as a truly religious Christian holiday,

peasants quietly continued with the old ways. The result is the

rich and eclectic mixture of old and new that characterizes

Christmas today. What better way to encapsulate the spirit of

Christmas than this fusion of different times, religions and

peoples to make a festival that has earned its place as one of

the favourites in our calendar.

Writer, teacher and psychologist, Jane

Gilbert comes from Devon, England, and lives by the sea in

Italy. After studying English Literature, she ran away to Brazil

where she travelled extensively and cuddled sloths. She likes

giraffes and curl reviver.

Article © 2005 Jane Gilbert

|