The Puritan Ban on Christmas

by Martha Doe

In the mid-17th century, a wave of religious reform transformed

the way in which Christmas was celebrated in England. Oliver

Cromwell -- a statesman and General responsible for leading the

parliamentary army during the English Civil War -- took over

England in 1645. Supported by his Puritan forces, Cromwell

believed it was his mission to cleanse the country of decadence.

In 1644 he enforced an Act of Parliament banning

Christmas celebrations. Christmas was regarded by the Puritans as

a wasteful festival that threatened core Christian beliefs.

Consequently, all activities relating to Christmas, including

attending mass, were forbidden. Not surprisingly, the ban was

hugely unpopular and many people continued to celebrate Christmas

secretly. In 1644 he enforced an Act of Parliament banning

Christmas celebrations. Christmas was regarded by the Puritans as

a wasteful festival that threatened core Christian beliefs.

Consequently, all activities relating to Christmas, including

attending mass, were forbidden. Not surprisingly, the ban was

hugely unpopular and many people continued to celebrate Christmas

secretly.

The Puritan War on Christmas lasted until 1660. Under the

Commonwealth, mince pies, holly and other popular customs fell

victim to the spirited Puritan attempt to eradicate every last

remnant of merrymaking during the Christmas period.

In the first half of the 17th century Christmas was an important

religious festival and a time when the English population would

indulge in a variety of traditional pastimes. The 25th December

was a public holiday, during which all places of work closed and

people attended special church services. The next eleven days

included additional masses, with businesses open sporadically and

for shorter hours than usual. During the twelve days of

Christmas, buildings were dressed with rosemary, holly and ivy

and families attended Christmas Day mass. As well as marking the

day's religious elements, there was also non-stop dancing,

singing, drinking, exchanging of presents and stage plays. The

population indulged in feasts of roast beef, plum porridge,

minced pies and special ale. Twelfth Night, the final day of

celebration, often saw a fresh bout of feasting and

carnivals.

It's no surprise that the daily celebrations often led to

drunkenness, promiscuity, gambling and other forms of excess.

Sixteenth and seventeenth century Puritans frowned on what they

saw as a frenzy of disorder and disturbance. In the Late 1500's,

Philip Stubbes, a strict protestant expressed the Puritan view in

his famed book The Anatomie of Abuses, when he noted:

'More mischief is that time committed than in all

the year besides ... What dicing and carding, what eating and

drinking, what banqueting and feasting is then used ... to the

great dishonour of God and the impoverishing of the realm.'

As well as disliking the waste and debauchery that went along

with the celebration of Christmas, the Puritans viewed the

festival (Christ's mass) as an unwanted remnant of the Roman

Catholic Church and, therefore, a tool of encouragement for the

dissentient community that remained in both England and Wales.

They argued that nowhere in the Bible had God called upon his

people to celebrate the nativity in this manner. They proposed a

stricter observance of Sundays, the Lord's Day, along with

banning the immoral celebration of Christmas -- as well as

Easter, Whitsun and saints' days. Preferring to call the period

Christ-tide, and thus removing the Catholic 'mass' element, the

Puritans reasoned that it should remain only as a day of fasting

and prayer.

King Charles I

had largely supported the existing traditions and festivities

but, as control passed to the Long Parliament in the mid 1600's,

Parliament set in motion their idea of completely eradicating the

celebration of Christmas. King Charles I

had largely supported the existing traditions and festivities

but, as control passed to the Long Parliament in the mid 1600's,

Parliament set in motion their idea of completely eradicating the

celebration of Christmas.

Shortly before the Civil War had begun in January 1642, Charles I

had accorded Parliament's request to make the last Wednesday in

each month a day of fasting.

In January 1645 parliament enlisted the help of a group of

ministers to create a Directory of Public Worship establishing a

new organisation of the church and new forms of worship that were

to be adopted and followed in both England and Wales. According

to the Directory, the population was to strictly observe Sundays

as holy days and were not to recognise other festival days,

including Christmas, since they had no biblical justification.

Parliamentary legislation embraced the Directory of Public

Worship as the only legal form of worship allowed in England and

Wales. Two years later Parliament reinstated the law by passing

an Ordinance affirming the abolition of the feasts of Christmas,

Easter and Whitsun.

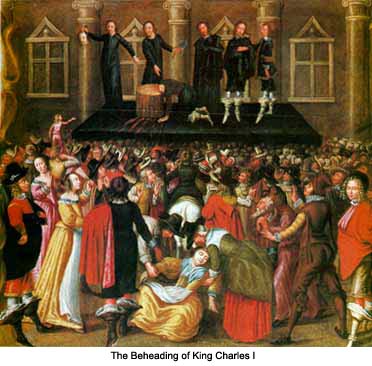

Oliver Cromwell regarded Charles I as an insurgent secret

Catholic who was subverting the Protestant faith. The Stuart King

was deposed and executed by Cromwell in 1649 and for the next

four years England was run by Parliament. But Cromwell had other

plans. He regarded the current system as ineffective and damaging

to the country. Supported by the army, on 20 April 1653 he led a

body of musketeers to Westminster and forcibly expelled

parliament. He then established himself as Lord Protector and

moved in to the Palace of Whitehall. The spectacular Banqueting

House is the only complete building of Whitehall to remain

standing to this day. The Palace was famously taken from Cardinal

Wolsey by Henry VIII and acted as the Royal residence until the

ascension of James I.

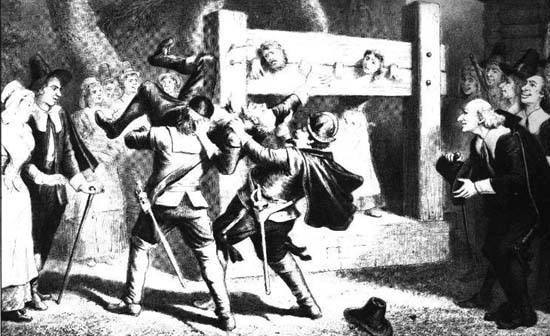

The Puritans believed that you would be welcomed in to heaven as

long as you worked hard in your lifetime, thus, enjoyment for

enjoyments sake was highly disapproved of. Cromwell ordered for

inns and playhouses to be shut down, most sports were banned and

those caught swearing would receive a fine. Women caught working

on the Sabbath could be put in the stocks. They had to wear a

long black dress, a white apron, a white headdress and no makeup.

The men had an equally sober appearance, dressed head to toe in

black and sporting short hair.

All shops and markets were to stay open throughout the 25th

December and anyone caught holding or attending a special

Christmas church service would suffer a penalty.

In the city of London things were even stricter as soldiers were

ordered to patrol the streets, seizing any food they discovered

was being prepared for a Christmas celebration.

Despite imposing such rigid measures on the common people, it

appears that Cromwell himself didn't quite live up to his

preaching. He liked music, playing bowls and hunting and, after

becoming Lord Protectorate, soon took to the high life. For his

daughter's wedding he even permitted a lavish feast and

entertainment fit for royalty.

In 1656 legislation was passed to ensure that Sundays were more

stringently observed as the Lord's Day and, thus, a day of rest.

The regular monthly fast day had always been hugely unpopular and

impossible to enforce and was subsequently dissolved.

Despite the threat of fines and punishment many people continued

to celebrate Christmas clandestinely. The ban had never been

popular and many people still held mass on the 25th December to

mark Christ's nativity also marked the day as a secular holiday.

In the late 1640s Cromwell tried to put a stop to these public

celebrations and force businesses to stay open. As a result,

violent encounters took place between supporters and opponents of

Christmas in many towns, including London, Canterbury and

Norwich.

Cromwell was Lord Protector until his death in 1658, whereby

Charles II was enthusiastically welcomed back to England to take

the throne as the country's rightful heir.

With the restoration of the monarchy in 1661, Oliver Cromwell was

once more a despised figure. Cromwell was originally buried with

great ceremony in Westminster Abbey, a famous gothic church in

London that houses the tombs of kings and queens dating back to

Edward the Confessor, as well as countless memorials to

distinguished English subjects. Upon taking the throne, one of

the King's first orders was to exhume Cromwell's lifeless body

and take it to be hung at Tyburn gallows, at the top of Hyde Park

near Marble Arch in London. This was the first permanent gallows

to be established in London in 1196 and was the main site for

public executions until 1783. This site is also famous because

105 Catholic martyrs were put to their deaths here from 1535 to

1681. A convent -- founded in 1901 -- now stands on the site, in

which around 20 nuns live and work. Visitors are welcome to visit

the church, which contains several Catholic relics.

Cromwell's body was decapitated and his head displayed at

Westminster Hall for over 20 years. Finished in 1099 this is the

oldest surviving section of the Palace of Westminster. The trials

of William Wallace, Sir Thomas More, Guy Fawkes and King Charles

I all took place here, so it was a fitting site at which to

display Cromwell's treacherous head. After changing hands over

the next three centuries, in 1960 Cromwell's head was finally

laid to rest at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, which he had

attended in 1616 to 1617.

Once Charles II was restored to the throne, all legislation

banning Christmas -- enforced from 1642 to 1660 -- was dropped

and the common people were once again allowed to mark the Twelve

Days of Christmas. Old traditions were revived with renewed

enthusiasm and Christmas was celebrated throughout the country as

both a religious and secular festival.

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Martha Doe contributes articles to a number of publications on

travel and history.

Article © 2005 Martha Doe

|