The Treasures of Arundel Castle

by Michael Magras

In the early 1800's, many of the owners of the Treasure Houses of England decided, in admirable recognition of noblesse oblige, to open their castles to the public. It appears, however, that the challenge of getting these properties ready for company varied greatly. Chatsworth House, the home of William Spencer Cavendish, the "Bachelor" 6th Duke of Devonshire, was in splendid condition even before he hired Joseph Paxton in 1826 to design its beautiful gardens. But consider Charles, the "Drunken" 11th Duke of Norfolk. His ancestral home, Arundel Castle in West Sussex, was largely in disrepair at the time of his ascendancy. Coincident with Chatsworth's relatively modest facelift, Charles had to initiate an ambitious restoration scheme that turned Arundel into the popular attraction that is now a regular fixture in the out-of-town excursions section of most London travel guides.

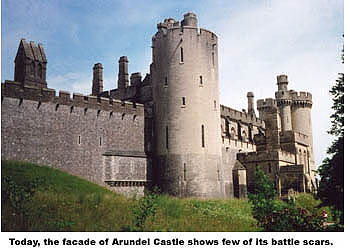

Anyone who approaches Arundel Castle from the town, perhaps by walking up the steep hill that snakes past souvenir shops and a 450-year-old restaurant, may not believe that such an imposing edifice once showed the ravages that seven hundred years and the impact of cannon ball bombardments can wreak upon even the sturdiest structure. (Glance at the barbican as you enter the castle, and you'll see large pockmarks from some of the attacks, first by Royalists and later by Oliver Cromwell's Parliamentarian force, waged during the English Civil War.) But the two centuries of repairs begun during the Drunken Duke's time have returned to the castle the stateliness and intimidating grandeur it appears to have enjoyed during the past millennium. It's possible, given the onslaughts it has had to overcome, that Arundel may be the best-preserved castle in all of England.

Anyone who approaches Arundel Castle from the town, perhaps by walking up the steep hill that snakes past souvenir shops and a 450-year-old restaurant, may not believe that such an imposing edifice once showed the ravages that seven hundred years and the impact of cannon ball bombardments can wreak upon even the sturdiest structure. (Glance at the barbican as you enter the castle, and you'll see large pockmarks from some of the attacks, first by Royalists and later by Oliver Cromwell's Parliamentarian force, waged during the English Civil War.) But the two centuries of repairs begun during the Drunken Duke's time have returned to the castle the stateliness and intimidating grandeur it appears to have enjoyed during the past millennium. It's possible, given the onslaughts it has had to overcome, that Arundel may be the best-preserved castle in all of England.

This Norman castle was built in the late 11th century on an existing Saxon fortification by Roger de Montgomery, Earl of Arundel, to whom William the Conqueror had given the land. To defend England's southern coast from the Continent, de Montgomery in 1068 built a 70-foot motte, or artificial earthen mound -- high enough to see the coastline and the surrounding landscape -- and then, in 1070, a bailey fortress flanking its 250-foot diameter.

The motte and gatehouse must have seemed a formidable deterrent against attack, but they weren't enough to stop King Henry I from taking the castle in 1102 -- albeit after three months of resistance -- from Robert de Belleme, de Montgomery's brother. After making repairs to the castle, Henry I bestowed it to his wife, Adeliza de Louvain, as part of her dowry. In 1138, three years after Henry's death, Adeliza married another Norman nobleman, William d'Albini II, who not only went on to become a prominent castle builder of the early to mid-12th century (and the first Duke of Arundel, a title that Henry II conferred upon him in 1155) but also was the architect of the keep, perhaps the most popular part of the castle today.

The keep, essentially an immense stone ring built atop the motte, rises thirty feet above the earthen mound and, at its top, provides beautiful views of the nearby River Arun, the South Downs, and the rest of the West Sussex countryside. But it's not a climb for the faint of heart. The first few dozen of its 131 steps, which run along one side of the motte, are relatively wide but occasionally cracked with age. The final steps, however, are quite narrow. Depending on your shoe size, you may be able to rest as much as half of each foot on each step. Moreover, the passageway leading to the top of the keep is narrow as well -- a design, common to most fortresses and castles, intended to stop enemy soldiers already encumbered by chain mail helmets and plated armor from storming a castle too quickly. That doesn't happen these days, but this clever medieval deterrent leaves modern visitors little room during the final few feet to the top. If you are at all claustrophobic, then you may wish to pass on the keep. But try to make the climb if you can, for the view that awaits you from the battlements is stunning.

The keep, essentially an immense stone ring built atop the motte, rises thirty feet above the earthen mound and, at its top, provides beautiful views of the nearby River Arun, the South Downs, and the rest of the West Sussex countryside. But it's not a climb for the faint of heart. The first few dozen of its 131 steps, which run along one side of the motte, are relatively wide but occasionally cracked with age. The final steps, however, are quite narrow. Depending on your shoe size, you may be able to rest as much as half of each foot on each step. Moreover, the passageway leading to the top of the keep is narrow as well -- a design, common to most fortresses and castles, intended to stop enemy soldiers already encumbered by chain mail helmets and plated armor from storming a castle too quickly. That doesn't happen these days, but this clever medieval deterrent leaves modern visitors little room during the final few feet to the top. If you are at all claustrophobic, then you may wish to pass on the keep. But try to make the climb if you can, for the view that awaits you from the battlements is stunning.

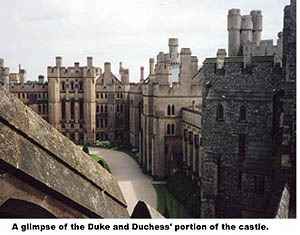

The two baileys that flank the motte are known today as the Quadrangle and the Tiltyard. The former encloses the state apartments and the residences of the Duke and Duchess of Norfolk and their family, who still call Arundel home. (The Tiltyard is closed to the public.) As you ascend the first, wide steps toward the keep, you can sneak peeks at the courtyard that provides entry to these residences. It's unlikely that you'll see the Duke and Duchess during visitors' hours, but the grounds are impeccably manicured and worth taking in.

When you enter the interior of the castle, be sure to pass by the state apartments and private living quarters. They are home to many beautiful works of sculpture, painting, tapestry, and furniture, including large portraits of every Duke of Norfolk. And those of you who feel that a sitting room is incomplete without dozens of family photographs perched on every table, mantelpiece, and sideboard no doubt will be charmed by the many candid snaps -- of the Duke and Duchess and, especially, their children and grandchildren -- generously scattered amidst the ornate furniture in the main living area.

Arundel Castle, like all the Treasure Houses of England, is as much an art museum as a royal residence. Fine works of art are on display throughout the building. Many of the pieces you'll see were either commissioned or acquired for the castle by the 14th Earl of Arundel, Thomas Howard. Some historians have suggested that he was perhaps Britain's most important art patron of the early to mid-17th century, which may explain his nickname "the Collector". Among his commissions are the famous "Madagascar Portrait" of himself and Aletheia Talbot, the Countess of Arundel, painted circa 1636 by Anthony Van Dyck. Stroll the castle interiors at your leisure, and you'll also see pieces by Peter Paul Rubens, Thomas Gainsborough, Sir Joshua Reynolds, and Antonio Canaletto. You can also see such personal artifacts as the 16th century prayer book and the rosary of gold and enamel beads that Mary, Queen of Scots, took with her to her execution. Interestingly, these mementos (excluding, fortunately, the auburn wig) are kept in a display case in the dining room.

While you're looking at the paintings on the walls, don't forget to pay attention to the walls themselves; for, in a building like Arundel Castle, the structure itself provides as much visual splendor as the adornments. The Regency Library displays only a fraction of the volumes that constitute the official Arundel Library, much of which has been sold off over the years, but it's also a warmly appointed room with paneling and vaulting of dark mahogany -- perhaps the finest example of a Regency interior anywhere in the world. Indeed, the ceilings throughout are masterworks of intricate timber-work and vaulting, and the Grand Staircase, a breathtaking work of craftsmanship in itself, brings you past restored bedrooms, all of which contain the original baths fitted during Victorian era restorations, as well as beautiful fabrics and tapestries.

A short article cannot possibly encompass all that you'll want to savor on a day trip to Arundel Castle, and you'll probably run out of time before you take in all that the castle has to offer. But be sure to find a few moments for the Fitzalan Chapel and a stroll through the gardens. This Catholic chapel, the burial site of all the Dukes of Norfolk, is named for Richard Fitzalan, to whose family the castle was passed when the d'Albinis ran out of male heirs. That many of his descendants were beheaded at the castle -- a fate that he, too, would suffer -- apparently did not dissuade Richard from building in 1380 this beautiful Gothic chapel. Although part of the castle, the private chapel is also attached to the St. Nicholas Anglican church, which has a separate entrance in London Road. In earlier centuries, this embedded design allowed the Dukes and their families to observe their Catholic faith in Protestant England, especially during the Reformation, when Henry VIII, after his divorce from his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, tried to abolish Catholicism through, among other things, the 1534 Act of Supremacy. In 1879, however, in what was known as the Fitzalan Chapel case, John Duke Coleridge, Lord Chief Justice of England, ruled that the Chapel was not part of the Protestant St. Nicholas' and thus should be a separate, Catholic ecclesiastical structure. Today, a glass wall and iron grille divide the Chapel from St. Nicholas'.

Take the steps up to the viewing area to see not only the interior of St. Nicholas but also the Fitzalan's intricately carved roof and choir stalls; a set of seventeen brasses that commemorate members of the Fitzalan family as well as fellows of the former College of the Holy Trinity, which Richard founded in 1380; and the tombs of eight deceased Dukes of Norfolk, including twin, rather grim effigies of the seventh Duke -- one that preserves his appearance when he died, and another showing his corpse in a state of considerable deterioration.

Take the steps up to the viewing area to see not only the interior of St. Nicholas but also the Fitzalan's intricately carved roof and choir stalls; a set of seventeen brasses that commemorate members of the Fitzalan family as well as fellows of the former College of the Holy Trinity, which Richard founded in 1380; and the tombs of eight deceased Dukes of Norfolk, including twin, rather grim effigies of the seventh Duke -- one that preserves his appearance when he died, and another showing his corpse in a state of considerable deterioration.

Outside the chapel is a much cheerier sight: the Fitzalan Chapel Garden, a small patch of all-white plants that is part of the larger, two-acre walled garden. Among the flora on view are apple trees and other rare shrubbery flanking a lead fountain, a central cut-flower border, and, to the west, an ornamental kitchen garden and Victorian greenhouse, originally erected in 1850 and since restored. If you visit Arundel from late June through later September 2005, you may want to take in one of the eight 90-minute guided tours planned for this year. Each tour will start at 11 AM and will be conducted by Gerry Kelsey, the head gardener; be sure to book ahead. But if you miss the tours, you're still free to roam not only the gardens but also the other forty green acres on which the castle is situated.

Finally, if you visit the castle between 20 and 29 August of this year, consider taking in the annual Arundel Festival. This popular outdoor gala began in 1977 with one performance at the castle and has since grown into a ten-day celebration of music, theatre, comedy, and children's shows that take place throughout the town. But the castle remains the center of attention: The festival's final-night Shakespeare play is staged outside the castle walls, and Barons' Hall, which contains much of the castle's impressive collection of 16th century furniture, is home to classical concerts and other events, such as last year's performance of works by Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Handel, and Bach by the English Chamber Orchestra. Aside from the new Shakespeare's Globe Theatre in Southwark, with its thatched roof and the chance for patrons to stand like groundlings at the foot of the stage, there aren't many places in or near London these days that let you experience a taste of what olde England must have felt like. A night of music and drama on the grounds of Arundel Castle, therefore, is a rare opportunity not to be missed.

It's fun to speculate whether the Drunken and Bachelor dukes anticipated the popularity that their generosity would attain when they first opened their castles to the masses. One has to assume they'd be happy to know that the only people storming the battlements these days are vacationers with rucksacks, armed not with halberds but with an appetite for history.

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Michael Magras is a freelance writer based in Falmouth, Maine.

In 2002, Magras received a fellowship in writing from the Vermont

Studio Center and was invited to the Stonecoast Writers'

Conference in Freeport, Maine. His nonfiction has appeared in

Vermont Magazine, Seven Days (a weekly newspaper in

Burlington, Vermont), and other publications.

Article and photos © 2005 Michael Magras

|